Take Risk! The Apex Interviews Richard Noble OBE

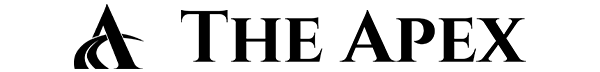

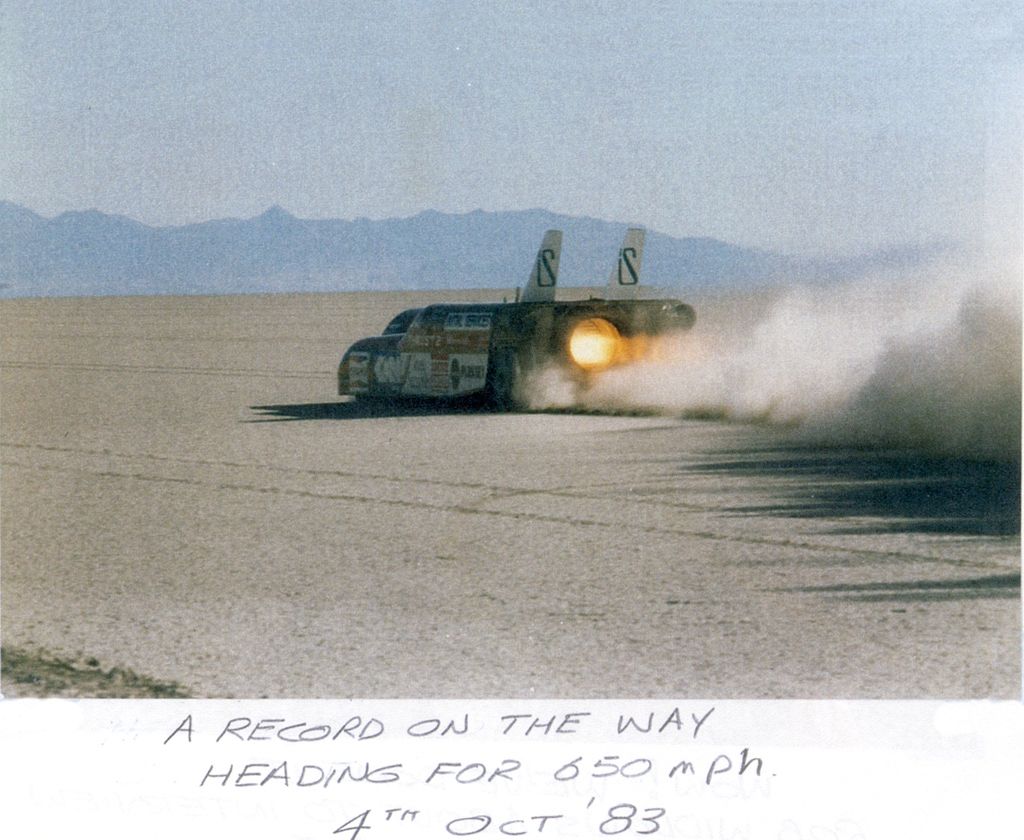

Our guest this week is Richard Noble OBE, a man who, in his own words, comes from an extraordinary age when Britain and her brilliant, risk-taking engineers led the world in aerospace developments. His relentless pursuit of success saw him bring the land speed record back to Britain in 1983 behind the wheel of Thrust 2 at 633 mph and, 14 years later, lead the Thrust SSC team to the first supersonic land speed record at 763 mph. In his recently published book, aptly titled ‘Take Risk’, he tells the story of the Thrust records alongside the trials and tribulations of bringing other innovative projects into reality on land, at sea and in the air - stories which he happily shared with us.

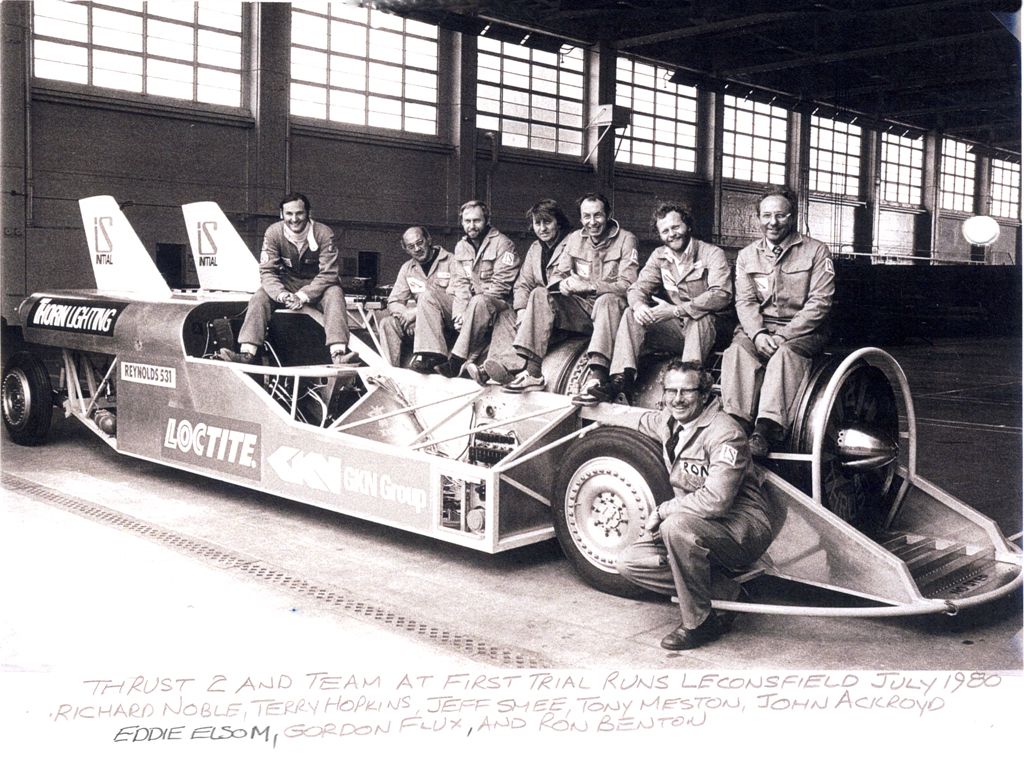

Hector Kociak interviews Richard Noble for The Apex by Custodian. Recorded and Produced by Jeremy Hindle. Transcribed by David Marcus. Edited by Hector Kociak & Charles Clegg. Also credit to The Ackroyd Collection where a lot of the fantastic original photos were sourced - http://woottonbridgeiow.org.uk/ackroyd/index.php.

In your book you describe watching John Cobb's Crusader on Loch Ness vying for the water speed record in 1952, and growing up with the intention of breaking the world land speed record. How did the young Richard Noble end up dreaming about being the fastest man on Earth, and were you always destined to be an engineer?

Well one or two things are wrong there actually - let's start at the beginning! John Cobb had just set up his base at Drumnadrochit, on the North Side of Loch Ness, and my dad was taking the family for a drive. There were a whole lot of people standing by the side of the road looking down on Temple Pier, and so we stopped to have a look - and there it was, John Cobb's jet boat, ‘Crusader’. It was the most fabulous thing I'd ever seen. It was all silver with red stripes on it; it wouldn't even look out of place today, it was astonishing. I never saw it run sadly, but I saw it there and at that moment I just thought wow, if this guy can do this, maybe there is a future in it for me!

Speaking of which - I think a question most car enthusiasts and speed freaks would love to ask is what it feels like to travel at over 600 mph. Could you tell us about that, and what memories stick out for you from the Thrust 2 and the Thrust SSC projects?

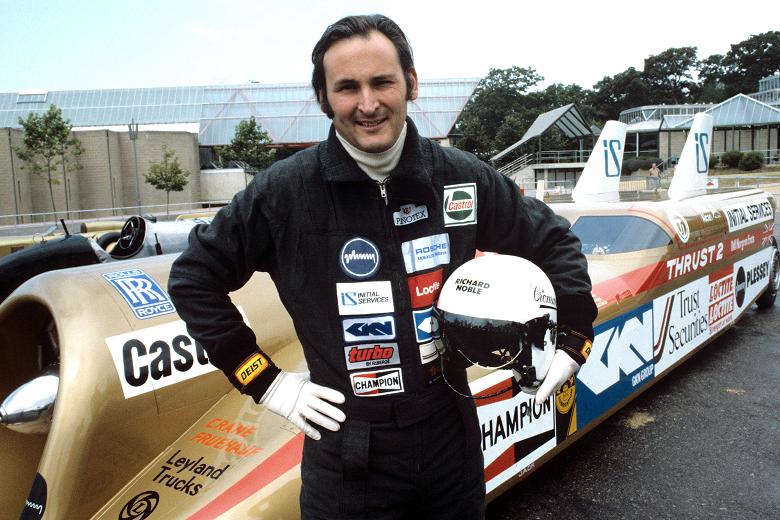

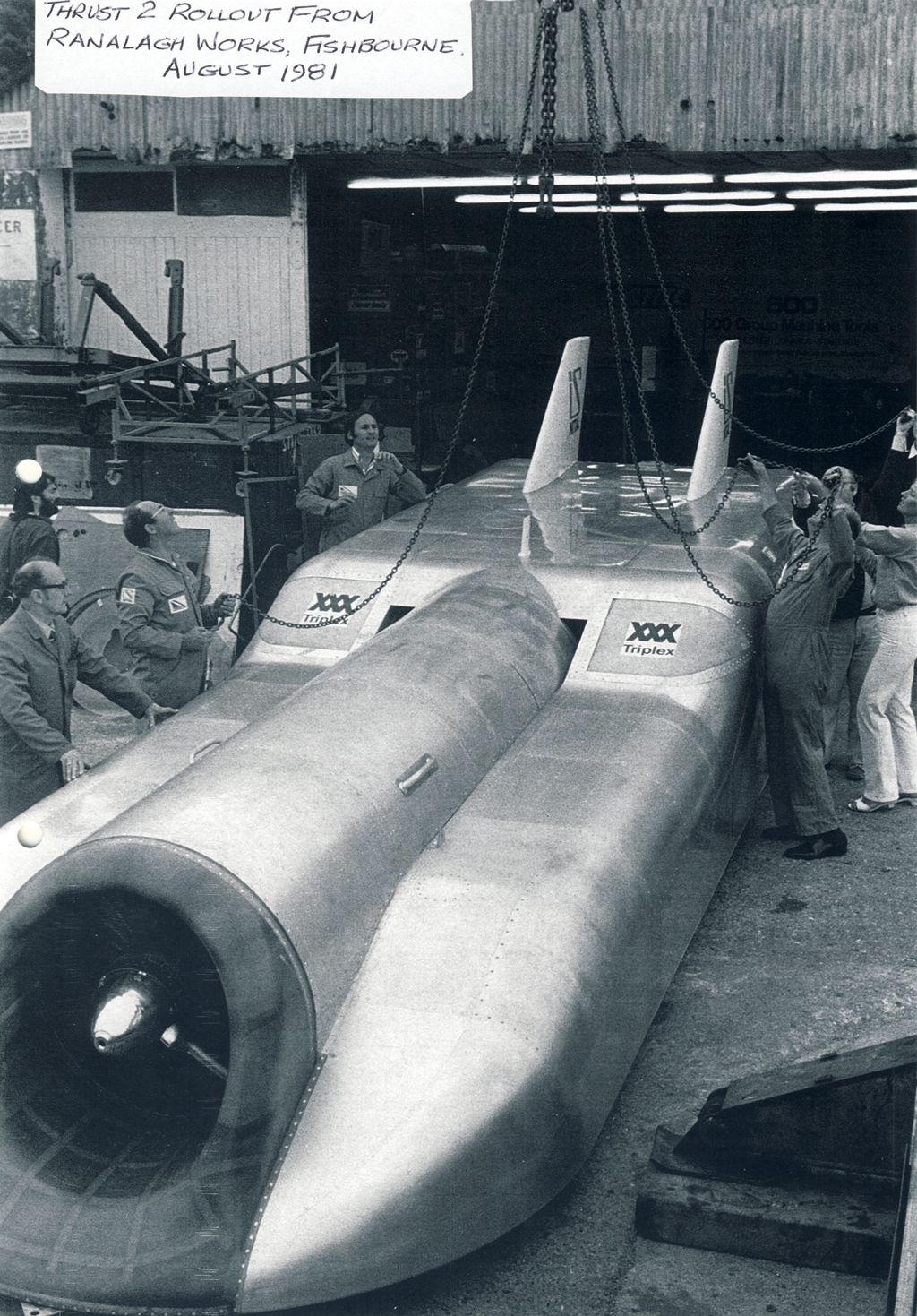

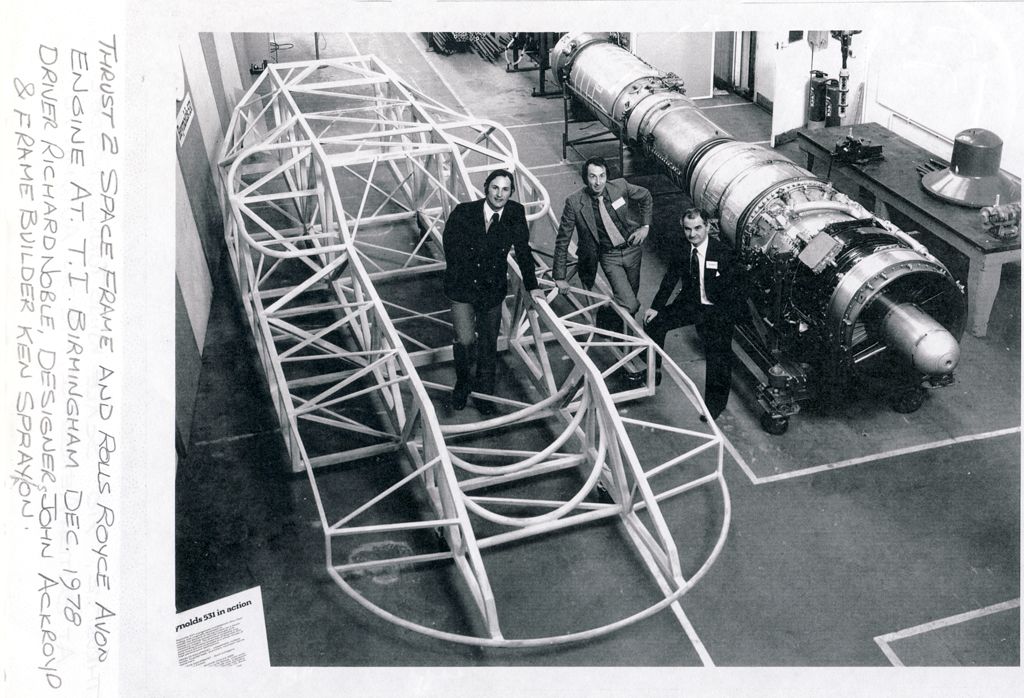

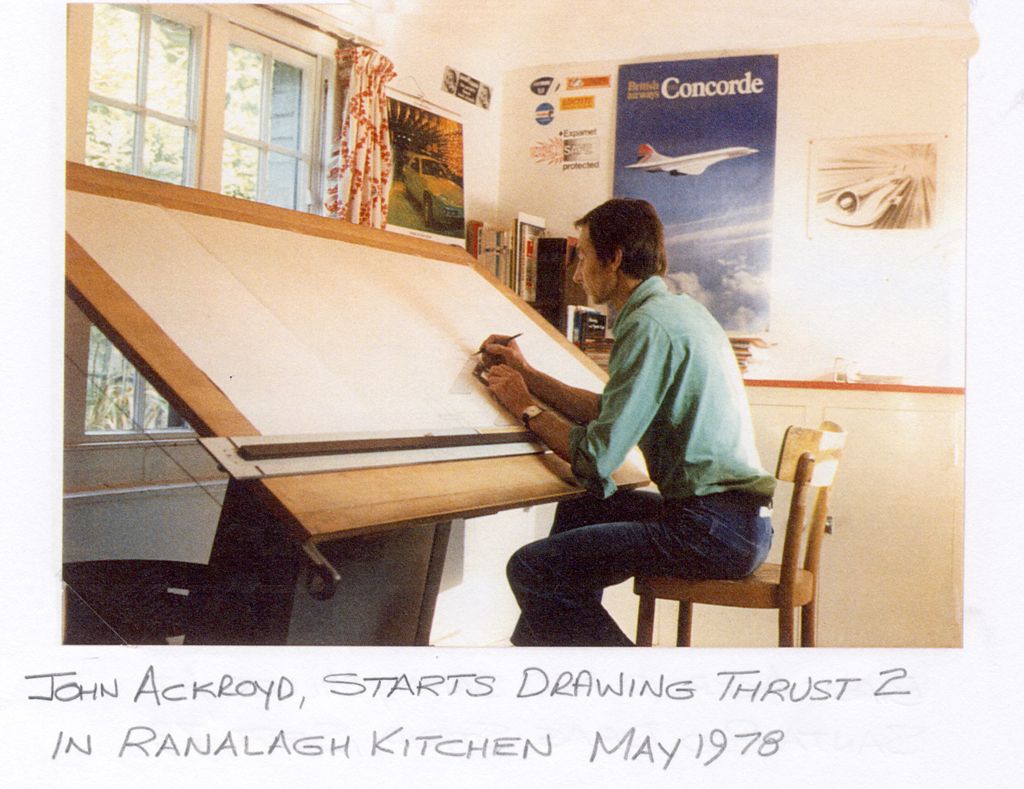

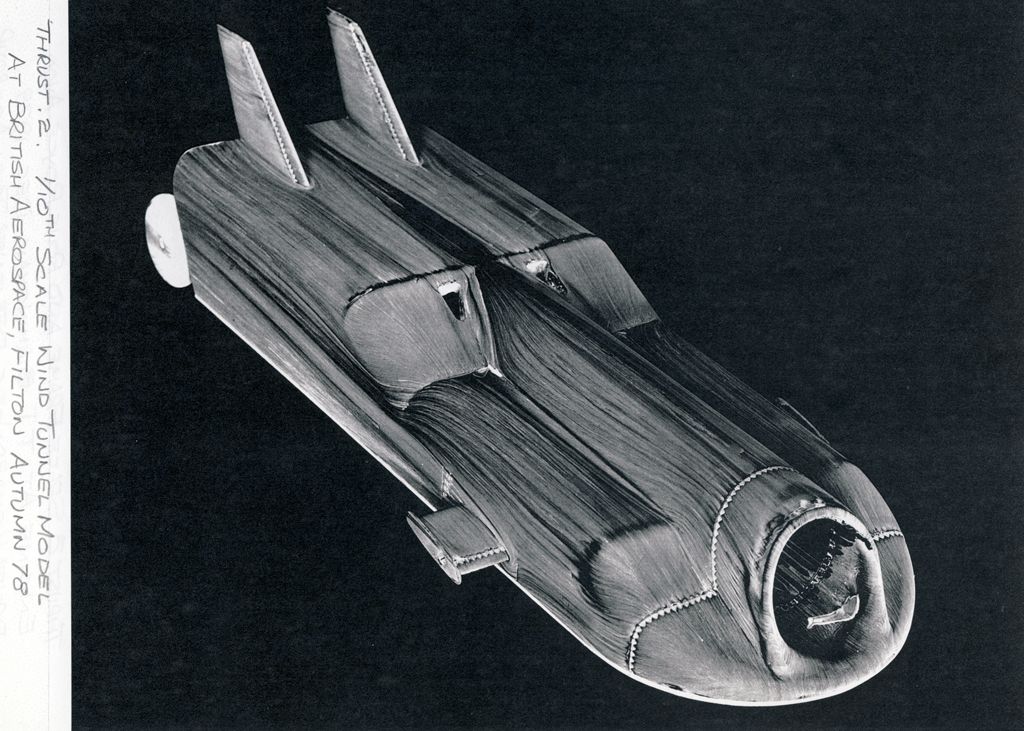

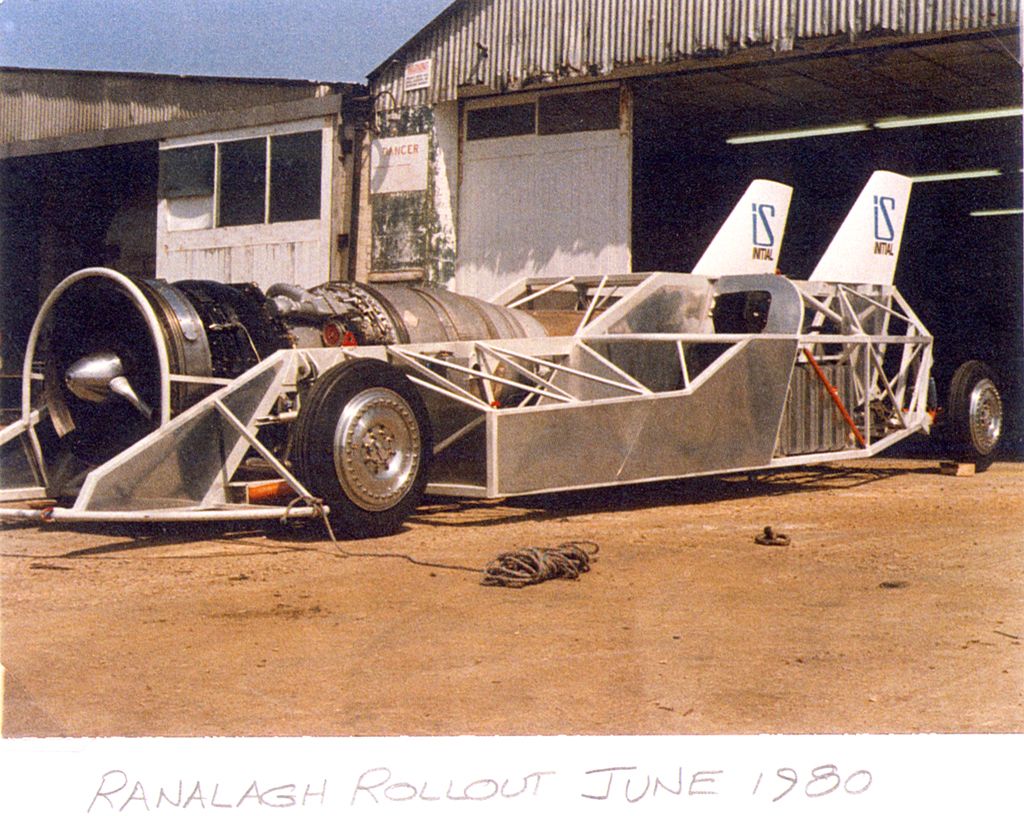

Certainly! I never drove Thrust SSC, because that's Andy Green's thing, but I've been over 600 mph 11 times in Thrust 2, which was a very clever car. It was created and designed by John Ackroyd, and I think it's probably one of the best performing land speed record cars of all time. A fundamental issue with land speed record cars is they generally underperform. When John and I started the Thrust 2 project, we set our design target at 650 mph and it ended up making a peak speed of 650.88mph, so it was highly successful. At high speed I could drive it to an accuracy of about 1.5 inches laterally. It was an absolutely amazing piece of engineering.

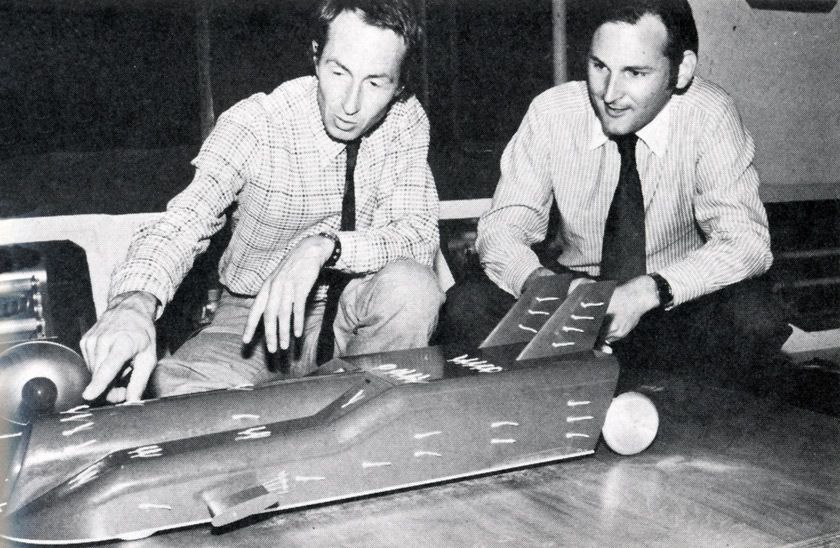

Driving it... yes, well, imagine that you're sitting in the cockpit of Thrust 2. Of course it's a British car, so we drove it on the right hand side to upset the Americans. You're sitting there with your left shoulder approximately three inches from a red hot Rolls Royce Avon turbine engine. You're pretty squashed in. We got the design of the cockpit right however, it worked very well. One of the crucial features of the cockpit design was actually the armrests. You wouldn't believe this, but it’s absolutely true. When you're driving the car you have a very low steering ratio, and you've got to get your movements absolutely right. Once you get into position, you lock your elbows so you can make those very small movements. In the old days when we first drove Thrust 2 we didn't realise this. Later on we got the armrests in - it made a hell of a difference!

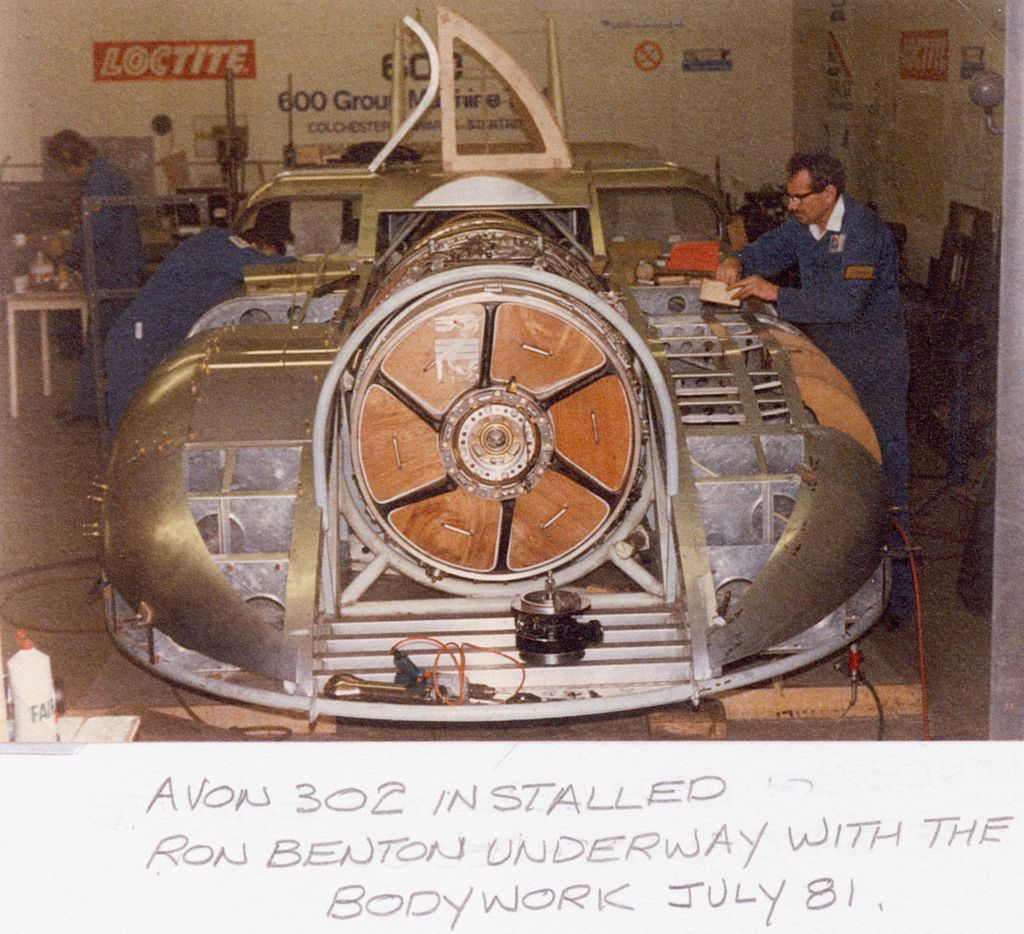

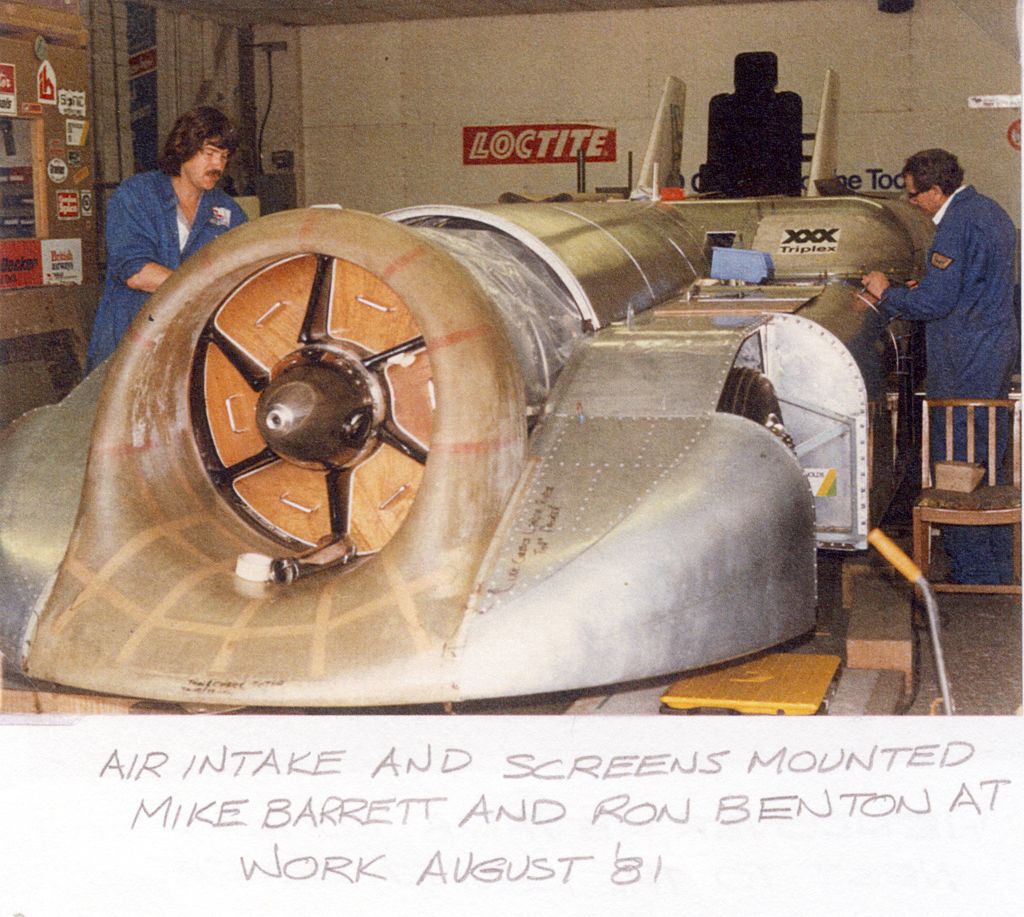

The car is powered by a large jet engine, a Rolls-Royce Avon 302 from a BAC Lightning F6 fighter plane. We've upgraded it a bit, so it's got about 17,000 pounds of thrust - over 30,000 horsepower. To start, it's connected up to a remote gas turbine called a Palouste, which spins up to speed and then pumps compressed air down a large canvas pipe into Thrust 2, and that spins the big engine up. You're given the signal and the team start up the Palouste. You press a button, the Palouste goes into overdrive, and suddenly you've got the engine winding up. You watch it very carefully, and when it gets to a certain figure, you open the high-pressure cock and at that point the fuel starts to flow into the Avon, and you get an enormous rumble as the giant engine comes into life...

That must be an unbelievable noise?

It’s not even very loud at that point, just running at idle. You run it up to 40%, and when the oil light goes out, then you've got to concentrate on the actual driving.

The thing about the course in the Black Rock Desert is that it consists of a lot of parallel lines, giving you a track width of 50 feet. You're going to drive down this track and you're sitting on the right hand side of the car, looking to follow the marker on the right-hand side. We had put it down using a Jaguar, which was ideal, as it seemed to go nice and straight(!). You sit there with the engine running, and you do all your engine checks and make sure everything is okay. In the meantime you're working the radio.

The fundamental problem is that you can only see about 2.5 miles to the horizon because of the curvature of the Earth. You’re going to run down a track which is 13 miles long, so you can't see what's happening on the other end. The secret is to have an aeroplane buzzing up and down the course; we call it up and just make sure we haven't got any stray Americans on the track... and all is well, and then the moment comes to go.

Credit: The Ackroyd Collection

You hold the car on its brakes with the left foot (all these cars are left foot braked), and then ease the throttle forward. What you're doing there is speeding the engine up until it gets to 92% of maximum RPM, as you read all the fighter aircraft instrumentation in the cockpit. 92% is critical, because if you go much faster than that, the car will start on locked wheels and that's no good. So you're holding it down on its brakes and you've hit 92%, you're doing your last checks: okay, we're ready.

Brakes off. Your foot comes straight off that pedal and you slam the accelerator with your right foot, pushing it down to the floor. That brings in the afterburner, and if you've done it well, you'll get it flaming within 30 feet of movement. Now you're off, and you've got 30,000 horsepower. You're running on aluminium wheels, which don't rip away the desert very well. The one thing you must never, ever do is let up. You must never come back on the throttle, otherwise it shows at the top speed. You've got to keep your foot flat to the floor. You're trying to hold the car within the 50 foot wide track, and it's sliding all over the place, a bit like a rally car really. You're bolting along watching the air speed indicator, and you get to a point where you're at about 300 mph. We've got two tail fins on the car and it starts to go straight and steady from about that speed. The important thing is to keep your foot absolutely flat to the floor, so you've got maximum power. Then you really start to pick up speed big time.

The curious thing about it is it's really rather boring, because there's nothing to see. There are no trees there. You do see the mountains start to change perspective very quickly, however. 300 to 500mph is a bit dull, but once you get over 500mph, it gets really interesting because the air flow starts to go supersonic, first of all over the intake arch, which you can see from the cockpit. You start to see the little shockwave build up there. When you get up to 615 mph it goes supersonic over the wheel arch, and you see the shockwave build up. There was one day when it was very cold, and at about that speed we got the whole car enveloped in a white cloud caused by the loss in pressure behind the shockwave.

Credit: The Ackroyd Collection

So you were driving blind?

No, I could just about see through it, it was okay.

You're coming up now to the start of the measured mile. This is where the fun starts. This is where the timekeepers have actually driven backwards and forwards at right angles across the course, in order to sort out controls and set up the timing lights. As you approach that it's fascinating, because your mental processes have sped right up and the whole thing is happening in slow motion. So you're very relaxed, you can see every single detail on that track go under your car at 600-and-something miles per hour. You're into the measured mile then, and you've got to keep going, you've got to keep accelerating right the way through it. You're trying to get the maximum that you possibly can through the measured mile, and then you come out the other end.

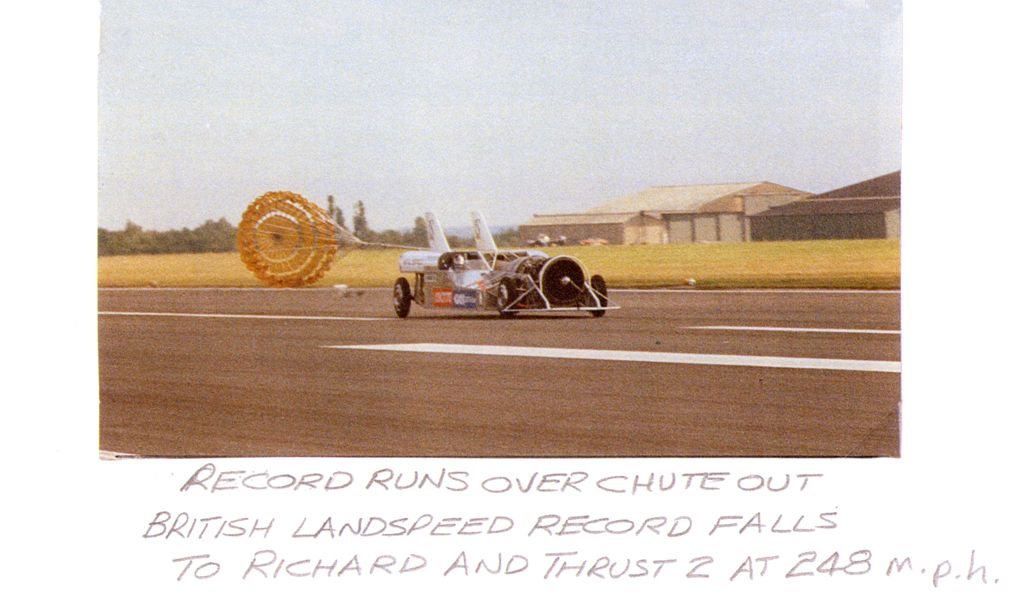

When you come out, you've got to be very disciplined, because you're into the deceleration and it is dodgy. You come back slowly on the throttle, which cancels the afterburner. You then count one, two, three; that cools the engine, and then you pull back on your throttle pedal which has a catch on top of it, and that shuts the engine off. Then you've got a risky situation, because what's happening now is that the air flow is no longer going through the engine at the volume it was before, and it's starting to build up at the front, and there's a danger the car will go sideways. At that point you've got to get the parachute out, and you literally just touch the button with your finger, and an explosive charge goes off at the back. The parachute is there immediately, and you're getting between 5 and 6 G’s of deceleration.

This is very violent stuff. 5G is over 100 mph per second of deceleration, and you get an extraordinary affect called the somatogravic illusion. When the car is decelerating as violently as that, the inner ear can't work properly, and you get the firm impression that you're driving vertically downwards through to the centre of the Earth. It's an extraordinary experience. With some very high performance jet aircraft they've had that sort of trouble with the pilots when they're trying to accelerate. Then while you're convinced that you're driving down into the middle of the Earth, after a few seconds it's all over and you're down to a leisurely 400 mph and it's incredibly boring. You want to open the hatch and get out, it's all over you know... still at 400! You've got to watch it down very steadily, down to 200mph, and at 200mph you can start to bring the wheel brakes in. You try to wheel brake the car as quickly as you can without locking the wheels, because of course you've got to turn around in due course and make the return run.

You bring it to a halt, you get everything shut down, and you immediately get your note pad out and you write up everything you can possibly remember, with all your checklists and everything else. You check everything, write everything down, and then before long the Jaguar is alongside you and you’re released from the cockpit.

That's what a land speed record is like.

I feel like I was right there. What an extraordinary description.

You've had a brilliant perspective on land speed records with Thrust 2, Thrust SSC and of course more recently the Bloodhound LSR project. Do the sometimes difficult experiences of Bloodhound suggest that the challenges faced by the teams involved in these records are changing as the bar is being set higher and higher over the years?

Of course it's more demanding in terms of the engineering and the physics and everything else, but what is so difficult in this case however is Britain - which unfortunately is going backwards in this respect. In this country people are totally and utterly risk averse. I can tell you some stories about all that but it just makes the whole thing incredibly difficult. These projects are unbelievably valuable, because what they do is they generate global exposure for the country, and that's what we're doing it for, the country. So to give you an idea, Thrust SSC, when we broke the sound barrier, had the largest website in the world. Bloodhound did 1.5 billion media exposures. What would a company pay to be a part of something like that? It's absolutely incredible, but unfortunately Bloodhound got marooned and wrecked by the UK Government, which was very sad.

It was difficult because I had spent about £31 million on it already. We got to the point where we had the car built and we were ready to go, but the big problem was obviously the money, to get the car shipped out to South Africa. We then landed this fantastic deal with the Geely car company in Hangzhou in China. I love those people, they were just absolutely great and Chairman Li was just terrific: 'come on, let's do it', he said - and we did. We got all the paperwork together and did the deal where he put the first tranche of his money in, which was a considerable sum. The UK Government had already signed up to review Bloodhound; we went through a program which took us the better part of six months while they reviewed the whole thing. Then I got a letter from the Minister of Transport saying fine, we're going to give you £4.5 million, which was brilliant. It was an astonishing team achievement, so we went for the meeting with them and they asked if we’d signed with the Chinese. We said yes, here's the contract, here's all the documentation, you can see the bank account. We met all their conditions, but for some reason the meeting then went sour.

They wouldn't talk to us after that. There were no more meetings. It was absolutely unbelievable. I think, personally, we had been set up - they didn't think we could do it, we had done it, and they just decided they were not going to pay. It was a hell of a thing. I went back to China and saw Geely and said guys, I'm terribly sorry, the British government has defaulted and they're not going to pay. Of course the Chinese were very kind and very understanding about this. I had a very nice letter from the Chairman saying that he understood it was not our fault. However it was pretty obvious that they thought if the British government wasn't going to pay its part, then why should they fund it? So there was no more money from them. Of course we were then in a battle to survive. 18 months later we had turned the Government around and the Secretary of State apologised for all this and renewed the deal, but by that time we were into Brexit and there was no money for anything. The Chinese were long gone, and there was no way we could survive, so I had to put it into administration - and that was that.

A sad story. In your book you talk about these events and also about this odd attitude that British society seems to have when it comes to engineering and science, on the one hand priding ourselves on incredible history of innovation and engineering and risk taking, and then on the other public institutions and an education system which seem intent on encouraging risk avoidance.

It really is terrible. It's just such a shame - we're talking about the next generation.

What do you think needs to change in order to turn things around?

We've got to be a lot brighter, and a hell of a lot smarter. All I can do is just talk from our own experience, but we were asked by the Ministry of Defence to set up the Bloodhound education team in order to take the project through every single school in the country. I thought this was absolutely terrific. Andy Green wasn't quite so sure, but it turned out to be a masterstroke. Before long we were engaging with 120,000 kids a year. We had three full-scale models of Bloodhound going round the schools, a few of them doing 70,000 miles a year. It was absolutely extraordinary. What we learned from this was that we were inspiring the kids. It was Minister Paul Drayson's idea; he spoke about Concorde all those years back, and that the project had inspired a huge number of scientists and engineers, and he wanted us to do the same. The apex of all this was running the car at Newquay in 2017. We had three public days there. 10,000 people paid to come and see the car run, and on the last day we had 3,000 excited school kids there, absolutely jumping up and down.

I had a bit of a problem with the engineers on the day; a lot of them were ex-Formula 1, and were wondering why on Earth we were dealing with education - Formula 1 doesn't! I said guys, this is what it's all about, we're here to talk to the kids. I came back about a half an hour later and it was going tremendously. Everybody was laughing and joking, the children were talking to all the engineers, and then we took the car out and did two 200 mph runs using the afterburner. With the bloody great noise and kids jumping around it dawned on me what was actually happening. These children are the product of the digital age - the only excitement they get is on a bloody screen, and the problem with a screen is that it is all faked. We know it's all faked, everything is bloody faked - however seeing a land speed record car drive down the runway there at Newquay, that's not fake. That's absolutely for real. It’s inspiring.

You feel it.

Oh my God yes! It shakes the whole Earth. It's terrific stuff.

Another thing that you talk about in your book is how successful projects, whether it's an aircraft company or a land speed record attempt, need not just good engineering but committed sponsors and, crucially, a committed team. What in your experience is the magic ingredient that separates success from failure?

There is one magic ingredient which is essential to this, which is the way in which the team works. We're often seen by sponsors as being a fairly dodgy organisation that might come good when risking their money. But we do generate an awful lot of publicity for them, and that's what they really want. However as soon as life gets difficult, for instance if we decide we're going abroad to go and run the car and we need the funds and everything else, they'll run away, cancel, drop out. If it looks like going south at all, they go, it's as simple as that.

We only got to America with Thrust SSC because of one guy – Jeremy Davey. We needed a million litres of jet fuel for the aeroplane we'd borrowed and nobody was going to help us, the usual problem. Jeremy, who ran the website, said ‘well, why don't we go to our worldwide followers? We've got this website, we were the first in Britain to do end-to-end electronic trading, so let's get them to put up some money’. So Jeremy and I wrote the appeal that night and we said to everybody: we've got a real problem, we've approached all these oil companies and nobody is going to help, but we need fuel. It's $25 a head, and in return for your $25, you will get a special fuel certificate signed by Andy Green. We only told Andy about that later(!).

We put the message out and the next morning there were 30,000 gallons.

Excellent!

It was fantastic. That's how we beat Britain, that's how we got away.

It strikes me that you had an incredibly motivated team of engineers. I think you recall people having to be told not to work on Sundays, because it was burning everyone out?

Yes. Years ago I used to teach management. It was an American company, and they were the top of the game, but I reckoned it was rubbish - there were better ways of working. I had run expeditions across Africa and Asia; you quickly learn when you're living with people how to work with them. While I was working with the Americans, I found a book by Abraham Maslow. He was an absolute genius and really understood how it all should work. He created a thing called the Hierarchy of Needs, which is a pyramid showing the different levels of motivation. In the book he goes on to say that if you get the fulfilment of needs wrong, then like in most of these large, hierarchical companies, the motivation levels will be very low. In a hierarchical organisation only 15% of staff will ever get to a high level of motivation, because they are running a system in which you don't really do anything for yourself - you just do what you're told.

He goes on to say that a significant number of the employees in any particular company will probably go to their retirement and deaths never knowing what they could really do if they were given the chance. So you've got to create an organisation that works the other way round and allows for self-actualisation. We create flat organisations and people are given the authority and the responsibility for what they do. They could actually go and tank the company if they wanted to, but it doesn't happen like that, because of course they are very serious about what they're doing. People realise that it's most unusual to start working in a situation like this, and it works very well. They get very excited and the productivity is unbelievable.

To give you an idea with the Thrust SSC project, our total cash expenditure was about £4 million, I think, and we were up against the McLaren Formula 1 team. Their budget was £25 million, and they were hopeless, they couldn't do it. So the teamwork side of it is absolutely crucial; if you get that right, then your staff turnover is absolutely minimal, because people really enjoy working in a way that lets them find out who they really are.

In our modern, interconnected world and with the benefit of technology, do you think it's easier or harder for these small motivated teams to bring imaginative, adventurous projects to fruition?

I think our problem is really the establishment. Britain is an entity that has grown from its colonial and imperial past; everything here is about hierarchical organisations, and some of the more important people in this world, in other words the accountants, the lawyers, and the venture capitalists, don't understand anything else. They like hierarchical organisations because they know somebody is in charge of it, they can point fingers, and all that sort of thing. They do not understand a flat company. It's all about control for them, and from our point of view, it's all about lack of control! You're actually passing the control to your team and letting them get on with it, really helping them to get through it all.

That's our problem. There are quite a few companies out there now practising better methods and one of the most famous is Haier in China, the washing machine company. It’s worth studying. We are very backward in this country, and we need some proper leadership.

I think that's food for thought for our subscribers, not only in business but probably also racing!

I wanted to ask you some final quick-fire questions. The first one is: if you could have been present at or participated in a particular historic record attempt, which one would it be?

I've been lucky enough to be on the Thrust SSC team and that is probably the biggest and greatest one ever, to break the sound barrier. That was a huge thing. But if you put that one on the side, then I would have loved to have been part of John Cobb's team in 1947, when he achieved the first over-400mph run working with a brilliant man, Reid Railton. That would have been a great experience.

Those years seemed to have been golden years for record breaking. The second question is: do you have a personal hero? Perhaps one of the Great British land speed record breakers?

Yes, well, Cobb was undoubtedly the greatest. A very quiet man, he didn't really like publicity but got enormous respect globally for what he achieved. He worked with and financed Reid Railton, who was a brilliant designer, and they came up with the Railton Mobil Special which was an incredible car. It took 16 years before the jet cars could exceed 400 mph. An extraordinary experience, and a great man.

Finally, looking back, if you were to come across a young Richard Noble today, what advice would you give him?

Ha! Keep going and get on with it!

Short and to the point! On that note I think that's a great way to finish what's been a really fascinating interview. Thank you very much for joining us today, Richard.

Absolutely my pleasure. Of course we haven't finished - there's more to come, and the book is at long last selling well, so that's great.

I read mine within two days...

Good man!

Richard book, 'Take Risk!' is available now from many bookshops including Waterstones or on Amazon here. You can also find out more about Richard on his website at http://www.richard-noble.com/.

In addition, there is a fantastic BBC Documentary about Trust 2 called "For Britain and the Hell of It" available on YouTube here: