On The Road With Jim Glickenhaus: Wall Street, Warhol, and Woodstock

Described by one magazine as possibly America's last real privateer, this week our guest is film producer, financier, director and automotive entrepreneur Jim Glickenhaus. With an enviable car collection which leaves motorsports fans - and especially Ferrari aficionados - slack-jawed with envy, Jim is also the owner and venerable leader of Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus, a proudly American low-volume manufacturer of elite road and racing cars competing in the world's most demanding races. An inspiration for anyone who has dreamed about becoming a race car constructor, Jim sat down with us to talk about his car collection and his life in motorsport, and share some fascinating stories from his long career.

Hector Kociak interviews Jim Glickenhaus for The Apex by Private Collectors Club. Recorded and Produced by Jeremy Hindle & Demir Ametov. Transcribed by David Marcus. Edited by Hector Kociak & Charles Clegg.

I just wanted to begin by asking how you got interested in cars. I've read about you as a young boy in the 1960s standing with your nose pressed to the glass of Luigi Chinetti's Ferrari dealership in New York every Saturday. What was it there that inspired you?

I always loved mechanical objects. Whenever my parents gave me a toy or a clock or something, I would always take it apart. I was very curious to learn how things worked. I had a bicycle which I would ride all over the place, and I had heard of Ferrari, and I knew that Mr Chinetti had a dealership that was about 20 miles from my home. So I cycled over one day and looked in through the glass; eventually he let me come in and then, over time, he let me sit in the cars and touch the steering wheel (not the shifter!). Over the years, we developed a friendship, and when he began working on race cars at his facility in Greenwich he would often send me out on my bicycle to get parts.

Mr Chinetti played a significant part in the history of Ferrari in North America at the time. By all accounts he was a real privateer's privateer and an accomplished racer who had somehow managed to convince Enzo Ferrari to make him the factory agent for the USA. I think you’ve mentioned that he was keen for you to go racing at one point, and that you developed a good personal bond with him.

That's right. The legend has it that Mr Ferrari was sitting in his office in Modena on Christmas Day in 1949 and he didn't even have enough money to heat the factory. Mr Chinetti went to visit him and wish him a happy holiday, and said ‘look, if you can build road cars, I can sell them in the United States’. Ferrari was reluctant, saying, you know, this car thing isn't really working and I think I'm going to go back to machine tools… but he changed his mind, built some road cars, and Mr Chinetti was able to sell them in the USA. So he became an integral part and, frankly, the future of Ferrari.

Mr Chinetti was also a very accomplished driver. He started racing before Enzo and knew that if he could find wealthy gentlemen drivers, he could talk them into buying race cars and going racing. His most famous outings were at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, where I think one time he wound up driving twenty three and three quarters hours by himself. His rich privateer gentleman driver was scared and Mr Chinetti told me that after 20 minutes the driver pulled over and he got in the car. Braking on the Mulsanne he heard a scraping sound and then shattering glass. The next time he went into the pits, it turned out it was a whiskey bottle that the driver had left in the footwell!

He also taught me one thing, which was no matter how wonderful Ferrari race cars were, they could be improved. It’s ironic that the last Ferrari to win first overall at Le Mans, which was back in 1965, was Mr Chinetti's N.A.R.T 250LM which was heavily modified in Greenwich. I actually worked on that same car. We did all sorts of things to it - drilled holes in it to make it lighter and bought better ignition wires because, as Mr Chinetti put it, the Ferrari ignition wires were crap. That was my first real experience with modifying cars.

Mr Chinetti was a great help; when I was a teenager I told him I was going to go to Europe to hitchhike over the summer, and that I wanted to see a Formula 1 race. He told me to show up on a Wednesday at the French Grand Prix, which at the time was in Rouen, and to tell the guys at the Ferrari transporter that I was a friend of his. So on the day I went up to the truck driver and said that. The driver didn't really speak much English and just shouted at me to start unloading the truck. Those were the days when everybody pitched in, so the Lotus guys showed up along with Graham Hill, and we helped them unload and they helped us, and at night we cooked pasta on a camping stove in the back of where the transporter was. I also met a young Jacky Ickx who had driven himself in a Fiat 124 from Paris overnight, and then drove the Grand Prix. Racing was very different in those days.

Luigi Chinetti Motors, New York in 1964. Credit: Dave Friedman Collection

It certainly sounds like it! What a story - I think times have changed slightly, and I suppose we have Mr Chinetti to thank for convincing Enzo to drop the machine tools and continue with the racing cars. Speaking of which, I've read that your first major race-to-road car was a Lola T70 Can-Am you purchased after having success in the film industry at a fairly young age. Did you have any memorable cars of your own before that or get involved in any kind of motorsport-based fun as a young man? I think I've seen mention of a 54 Studebaker going at crazy speeds up and down motorways...

Yes, my first car was one I built up myself, a ‘54 Studebaker that I put a 421-cubic-inch Pontiac Catalina motor into with three carburettors that I got out of a junkyard. I installed a Corvette gearbox and a Shafer clutch too. In those days there were mail order companies that would sell you bell housing adaptors, clutches and motor mounts, so you could install anything in anything. That ‘54 Studebaker was a very cool and beautiful car, designed by Raymond Loewy who designed the Coke bottle and later the Studebaker Avanti. I used to go to Wingdale, which was a very small quarter-mile drag strip about an hour north of where I lived, drag race and try to drive it home. If it broke down, I would tow it back.

After I wrote and directed The Exterminator in 1980, I took some of the money that I made from that and invested it with my dad on Wall Street. With the rest I went out and bought a Ferrari. It was a 275 GTB/2 Long-Nose Alloy Coupe. It was a wonderful car; it had entered the Targa Florio under a privateer, and at the time I remember I paid less than $6,000 for it.

How extraordinary.

I loved it. I drove it 55,000 miles in rain, sleet, and snow. On the day that they dropped the speed limit to 55 mph in the United States because of the situation in Iran, as an act of civil disobedience (I was young and stupid back then) I drove from Boston to New York city in 2 hours. You can work out the average speed. I was hoping to get arrested and make a political point, but no one stopped me. I had an amazing time in that car. People were kind of interested in the 275 as a sports car, but they had no interest in old racing cars. I remember begging my father to loan me the money to buy a 250 GTO on a trailer for about $6,000...

Yes, in retrospect that sounds like it would have been quite a wise decision.

In later years I would mention it to him, and he’d reply saying ‘Look Jim - back then, anything you bought was a wise decision!’ He said if I’d bought into Microsoft’s IPO I would have been a lot wealthier than if I had bought my 250 GTO, and it kind of put it in perspective. But I loved race cars and I loved the idea of driving them on the road. I saw a small ad for the Lola in the New York Times. This was, of course, way before the internet or anything so the Sunday New York Times had a sports and competition cars section in the classifieds. All the enthusiasts would buy the paper at midnight on Saturday, so as soon as Sunday morning came you could call up. Sure enough, I saw the Lola T70 ex-Donohue Penske listed and decided to ring up.

At the time it was owned by Andy Warhol Productions, and the guy on the phone was Andy's business manager. Warhol had bought it to use in a movie that was sort of a spoof of Terence Rattigan’s film “Yellow Rolls Royce”. Warhol never got around to doing it, but he wanted to sell the car. So I bought it. It was a flat out Can-Am race car with no windshield and no mufflers, just as Penske and Donohue had raced it. It actually had won eight major Can-Am races and a few championships. In those days no one knew what a Lola was; as long as it had treaded tires and seat belts and headlights - well, I cut headlights into it - you could road register it. So that’s what I did. After a while of driving it around the cops got notice of it and suggested that maybe I should put a windshield in. I wrote to Lola and I gave them the serial number of the car, and after a month I got a reply by air mail in which they offered to sell me a coupe body. That’s the one I put on, and that was my first race to road conversion. I've owned that car since 1972 and have probably put 40 or 50,000 road miles on it. It taught me a lot about what makes a really cool road car.

Jim keeps his remarkable car collection in an old beverage warehouse tucked away on a residential street in Sleepy Hollow, New York. Credit: Hide Ishiura / Source: Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus

I don't think many people can boast such interesting first cars for their collection. On that topic, 1967 seems a real stand-out year for you as a collector, with you owning the Bandini/Amon Ferrari P3/4 which won the 24 hours of Daytona, the Ferrari 412P which took 3rd at Spa that year and your Bruce McLaren Ford GT Mark IV which came in 4th at Le Mans. How did you come to own those, and what is it about those cars and that year that is so special to you?

Well, 1967 was an amazing year. I turned 17 and the future was limitless. The music was just fantastic, the films were changing, the cars were magnificent and it was really the dawn of understanding aerodynamics. In 1967 half a million people were at Le Mans. The audiences were incredible. The music scene was exploding - I went to Woodstock in ‘69 and the groups that you heard and the influence that it had on music for many years was amazing. So those summers of ‘67, ‘68, ‘69, always stuck in my head.

The Ferraris of the time were still being built to look very beautiful, and the Ford Mark IV was perhaps the first time that any scientific thought was given to aerodynamics. I think Ferrari before that had made wind tunnel models, but Ford used a full size wind tunnel on that car. I also think the ‘67 prototypes were really the last prototypes that looked like an enthusiast’s dream sports car but were still possible to drive on the road. Le Mans was a street circuit and you also had the Targa Florio, which was basically roads; even purpose built race tracks back in the ‘60s were a lot curvier and twistier, more like roads, and they weren't billiard smooth. That really appealed to me.

After ‘67 the French wanted their cars to be able to compete, so they dropped the prototype specifications from 7 litres down to 3 litres, and both Ferrari and Ford stopped racing for a while. Then they came back with “production sports cars” like the Porsche 917 or the Ferrari 512S / 512M, the kind of thing Steve McQueen featured in his movie Le Mans. With the 917, Porsche had allegedly built 25 examples, but later admitted that a lot of them were unable to run. When the FIA inspector came round and saw them all parked in a garage, he luckily pointed to the one that would start, and so the car got homologated. Those were very interesting, but not really great cars. The 512 had a lot of problems as it wasn't really the best design, and the 917 was a complete widowmaker in the beginning.

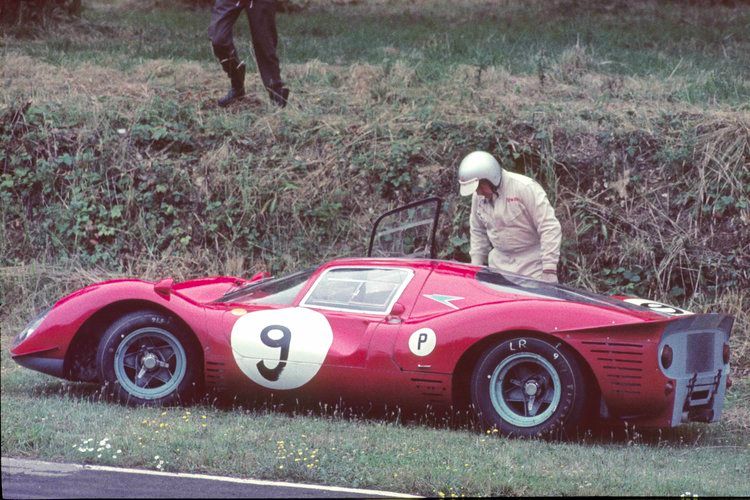

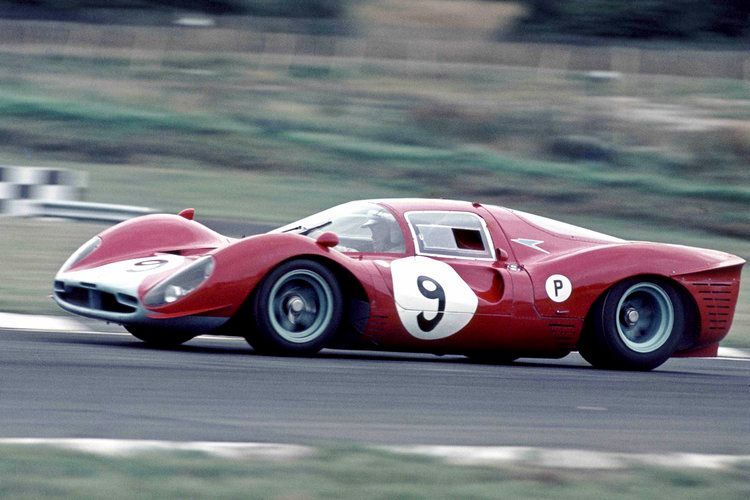

Jim's 1967 Ferrari 412 P Chassis 0854 which finished 3rd at the 24 Hours of Spa. Source: Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus

I think the 1971 917K had a tubular frame built from magnesium or something like that.

Yes, the chassis was completely brittle. They actually welded a tyre pressure gauge into the chassis and told the drivers that if they saw the gauge reading go down, it meant that the chassis was cracking and was probably going to come completely apart. So you’d have to get out of the car quickly but not hit the brakes so it wouldn’t blow up. Your feet in a 917 are also in front of the axle, as a lot of people unfortunately learned. Those were different times, and it was pretty dangerous. Ferrari did work on the 512 a bit, and interestingly enough Mark Donohue and Roger Penske bought one and really developed it and made it a much better car with American ingenuity. But it’s fair to say that both the 512 and the 917 were really impractical to drive on the road.

Compared to the P3/4 and the 412, as you said, you wouldn't turn up at a friend's house in a 917!

No, exactly, and people did drive those cars. Dean Martin Jr. drove one of the Ferrari 412Ps for years in LA, and I've been able to put a lot of miles on mine. Listen, they're not like a Toyota, but you can certainly wake up early on a Sunday morning and drive them in a hundred mile loop, stop for lunch and then drive home, and they work. I have driven my P3/4, the Daytona winning car, on the historic Targa Florio. I met Nino Vaccarella again and he drove it with me, and at the 100th anniversary of the Targa Florio the government of Italy invited that car back and they shut the original section of the Targa Florio from the start to Cerda, and we drove on the whole road with no oncoming traffic. It was an amazing experience.

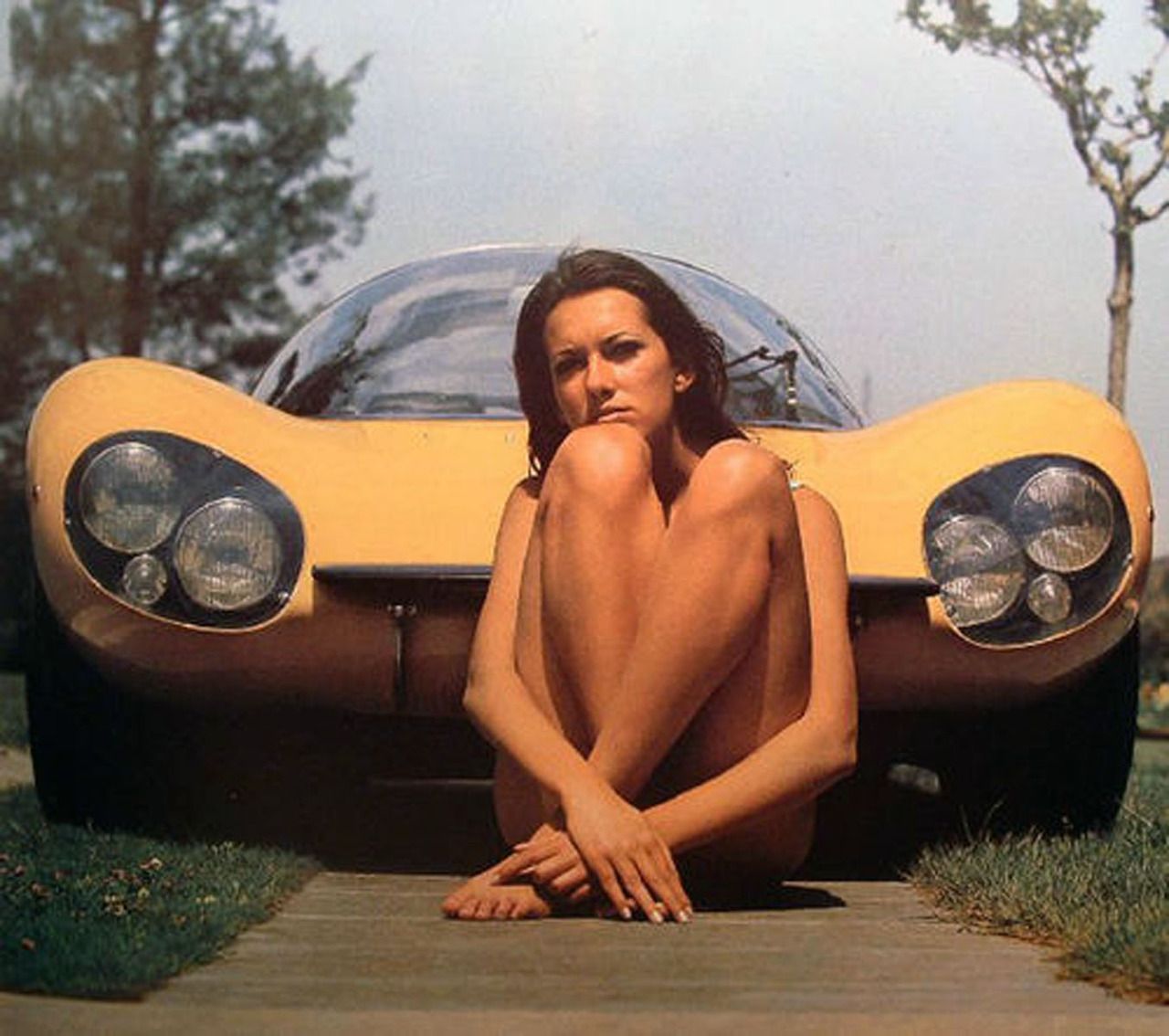

1970 Dino Competizione by Pininfarina, a one off show car created by Pininfarina, which Jim purchased directly from Pininfarina. Source: Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus

Doing my research on your collection it struck me how often Pininfarina appears in your story. I believe you bought the 1970 Ferrari Modulo and the 1970 Dino Competizione directly from them, and then in 2005 Andrea Pininfarina approached you with a proposal to build your dream car, which eventually became the incredible Ferrari P4/5 by Pininfarina. What influence has Pininfarina had on the story of SCG?

I think that Pininfarina represented the purest and best form of design for Ferraris. I think Mr Ferrari was very interested in the engines, the gearboxes, the chassis, the brakes, but he knew that he really did not have an artistic or aesthetic sense for design. He relied on Pininfarina to clothe his creations. He had other coach builders, but I think it's fair to say that Pininfarina was the major coach builder for Mr Ferrari. The story goes that when they unveiled the F40, Mr Ferrari had not seen it before the unveiling. When they took off the cloth, he just said ‘bella macchina’. He knew enough to leave Pininfarina alone and to let them do what they wanted to do.

After Mr Ferrari, Luca di Montezemolo came in to run the company in 1991, and in fairness to Luca, he revitalized Ferrari. At the time they were making very poor road cars. The 328s, the 348s as well as Formula 1 were all a shambles, and Luca revitalized both the production, the road cars and the Formula 1 team.

1970 Ferrari Modulo by Pininfarina, a one off show car created from a Ferrari 512S race chassis and engine by Pininfarina in 1970. Although the race chassis ran, the show car never ran. Jim purchased the Modulo directly from Pininfarina and spent four years finishing the car to make it drive. Source: Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus

As to the P4/5 by Pininfarina, it started with the response to the supercar which became the Ferrari Enzo. Luca’s brief was to make it a visual homage to Formula 1, unlike the F40 which looked like a Le Mans prototype or a road going prototype. He became much more hands-on with the design than Mr Ferrari; Sergio Pininfarina told me that he and Luca would meet frequently in between Modena and Turin. However at that time there was some push back from the public when the Enzo came out - people said it wasn’t beautiful, that it didn’t look like a Ferrari. There was pushback on some other cars too, with people complaining that the 550 and such like were just very bland.

And so Sergio Pininfarina and his son Andrea (who was really the driving force at that time behind Pininfarina and running the company) wanted to find someone who would commission a coach-built Ferrari that would enable them to make, in their minds, a beautiful Ferrari again. It was a difficult thing because they needed to find a customer who first and foremost could write the cheque, but secondly who would not be afraid of ‘what Ferrari might do’ if you embarked on such a venture. At that time - and I think perhaps even today - people were just terrified. I don't know what people thought Ferrari would do to them if you annoyed them.

Well I suppose today the worry would be that they won't even let you buy the first car, which would let you buy the second car, which might eventually get you the third.

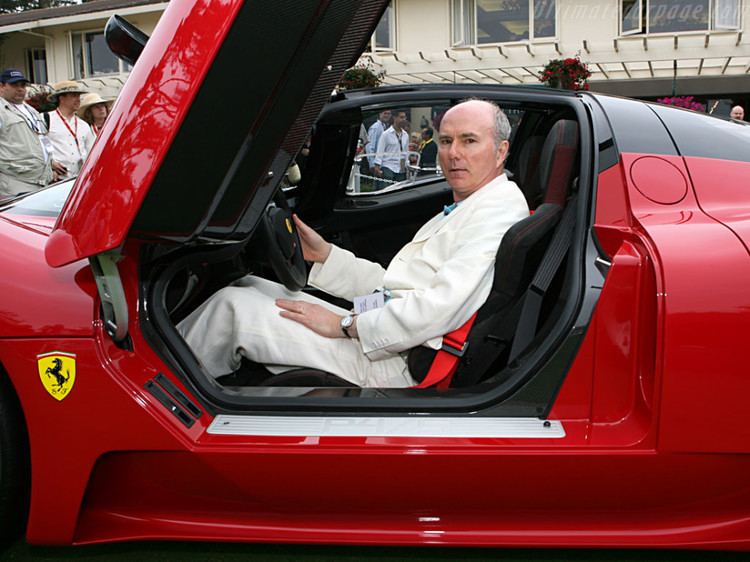

Exactly. Andrea Pininfarina got in touch with me through Christian Philippsen who was a mutual acquaintance; Christian met me at Villa d'Este where I was there with my Duesenberg and asked whether I would consider commissioning a one-off car with Pininfarina. I said that I would consider it. They asked me what I would propose to do, and I said I wanted to take the latest and greatest Ferrari supercar, the Enzo, and re-imagine it as an homage to my P3/4 and the great historic Ferrari racing cars like the Dino Competizione and the 512S. Andrea thought about it and agreed. Shortly thereafter I got the chance to buy the Maranello Concessionaires 412P, so I now had two Ferrari P cars. I think Pininfarina was momentarily scared that instead of paying for this one-off project, I had bought another “P” car instead, but I explained that no, they were completely unconnected. I still wanted to do the one-off.

The P4/5 by Pininfarina is a funny car. Ferrari had nothing to do with it, other than of course building the original Enzo. I bought the last brand new unsold Enzo at a Ferrari dealer in California. They didn't have a clue what I was going to do with it, and I think US customs was a little confused when they saw me taking a brand new Ferrari from California and shipping it over to Europe.

When it arrived at Pininfarina, I drove it a little and we went into what I wanted to do. There was a lot to improve mechanically. The original Bridgestones on the Ferrari Enzo really were terrible. The car didn’t have enough turn-in, and had so much front overhang that it was virtually undrivable on the street. On some crowned roads you had to straddle the middle of the road so the car wouldn't bottom out and it was extremely difficult to go from a flat road up a hill, or to get it on a tow truck if you needed to, or into a transporter. So I wanted to shorten the front overhang and take a lot of weight out of it. I also didn’t like the interior. It wasn’t intuitive, so I explained how I wanted to move a lot of controls around. That’s how we began the process.

2006 Ferrari P4/5 by Pininfarina. Source: Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus

It was quite a comprehensive re-engineering then?

Oh yes. We re-engineered 200 systems on the car, and used design cues from my P3/4, the 512S, the Dino Competizione, and other cars. I think the great thing that Pininfarina did was really push me to make a design that would stand on its own rather than just be a replica of the P3/4. My kids were instrumental in having me agree to that, because they liked the more modern look of some of the sketches, so that’s the direction we went in.

Ferrari knew nothing about the car. There were rumours on the internet however, and when the car was just about finished, Luca heard about it and flew to Turin. Andrea said he knew it was serious when Luca shut off the helicopter on arrival. Normally he would leave it running, come into Pininfarina, yell and scream, get back in the helicopter and fly away. This time he shut the helicopter off. He came in and said, ‘How could you have done this? How could he have done this? This is not a Ferrari, we will never work with Pininfarina again! He will never buy another Ferrari!’ and so on, and Andrea said, ‘Luca, I don't think you understand. Our business for a long time has been coachbuilding. We have re-bodied many vehicles over the years, and this is what we do. He is a client, he wanted to do it, and he doesn't care if it's a Ferrari. He told us he's perfectly happy to put a Pininfarina badge on the car.’ Then Luca asked ‘Who is this guy?’ and Andrea told him it was Jim Glickenhaus, and he said ‘Oh, that guy.’

He asked about the story behind the Daytona P 3/4. Andrea explained that basically after Le Mans, the car was burnt and scrapped by Ferrari, and I had found it and resurrected it. Incidentally Ferrari sent a letter to me that I shouldn't have taken parts out of their garbage and resurrected chassis 0846 but anyway...

You can't keep a good Ferrari down, clearly.

After Luca heard that, he wanted to see the car. Then the whole thing went full Italian opera. I had told Andrea I was fine with Luca seeing the car, but he was a little annoyed at how vociferous Luca had been, so he refused to let him see it. ‘It's Jim's car, you just told me it's not a Ferrari,’ and so on. Luca insisted, so Andrea went into his office, shut the door, had a couple of cappuccinos while pretending to call me, and finally told Luca that I had given permission to see the car.

Now the reason for all of this was that the car was already on the roof under a tarpaulin, where they had unveiled it on a turntable. So they went up the stairs and Luca was still fuming (‘This will never be a Ferrari, and we're going to kill him, and we're going to kill you’, sort of thing) but they finally got to the top and unveiled the car. Andrea said it was the only time in his life that he saw Luca di Montezemolo stop talking. Apparently Luca looked at it and said ‘Oh, it's beautiful, it's a Ferrari. Let's go have lunch.’

A happy ending. What more do you need?

That was it and that's how the car became a Ferrari. We then argued about what to call it. Luca just wanted to call it “Ferrari P4/5” and Andrea insisted that Pininfarina's name was on it. Eventually everything got settled. It's an official Ferrari, it's in their records, in their parts computer under Ferrari P4/5 and it has a VIN number.

1947 Ferrari 159 Spyder Corsa, the oldest existing Ferrari and the third car Enzo Ferrari made and the first customer car. It also has a strong race history including winning the Turin Grand Prix. Source: Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus

As we discussed earlier, you're well-known for road registering your cars and putting significant miles on them. I think you've even taken your precious 1947 159 Ferrari Spyder Corsa on a trip to Sicily, as well as racing it. Certain people in the collector community would probably blanche at the idea of taking some of these priceless cars out onto the road, let alone the track. Why is your attitude different, and do you think it maybe shocks other collectors?

I think that some people really have no clue what real race cars are. Real race cars roll out of the factory and on the first day they're modified. Mechanics take things off, they put things on, they cut holes in them, they file things down, they make them go faster, and if they break they fix them. If there's two P4s sitting in the pits and one crashes, they take parts off the one that crashed and use them on the one that didn't.

I'm always amused when you go to Pebble Beach and people are judging competition Ferraris and making statements about them that are just totally absurd, like ‘this is original’. There are no original Ferrari race cars, none, zero, end of discussion. So the originality of it or changing it for use never bothered me.

For example, if you want to drive a race car on the road you have to modify the brakes so that they work on the road at slow speeds. You have to put on cooling fans or the cars will overheat and destroy their engines. You often have to change the gear ratios so that they are much lower, because the speed you go on the roads is much lower than on a race course. You also have to modify the clutch so that if you're stuck on a hill at a red light you can get going without rolling backwards into a pickup truck and demolishing the car. That’s why I never had any issue with modifying my cars. I always try to do it sympathetically, of course, so that it can be put back to how it was originally.

I also love driving these cars. I've never understood guys who have F40s with 300 miles on them, who take them in an enclosed trailer to a concours, push them off and stand around all day talking about their immaculate F40 with 300 miles on it. It's ridiculous. I own Ferraris that have gone 2,500 miles in 24 hours in a race, and it certainly didn't hurt their value. My Ford GT Mark IV went 3,300 miles in 24 hours - that didn't hurt its value. The most valuable Ferraris, the “P” cars or the 250 GTOs, don't even have odometers! So this is almost like a fetish that people have for low mileage cars, and not to be too crude about it, I once made the remark that not driving your Ferrari is like not having sex with your supermodel girlfriend because she'll be more desirable to the next guy that comes along. I mean, really, it's insane.

Jim's 1967 Ferrari 412 P Chassis 0854 which finished 3rd at the 24 Hours of Spa. Source: Road & Track

That's quite a powerful way of putting it and I suppose the tyranny of matching numbers and things like that doesn't hold much sway with Glickenhaus?

No, it's completely meaningless. When Ferrari had a car and it broke, they would take chassis plates off one car and put it on another car and race it, they would re-stamp engines, and they would re-stamp chassis. If a chassis crashed, they would cut part of it off and weld on another part. Given all of that, the idea of a pristine original race car is just absurd and quite frankly there is a lot of bullshit at some of these concourses about ‘pristine Ferrari road cars’.

There are restorers who make a huge amount of money convincing wealthy people that they have the knowledge to get them a prize at Pebble Beach or wherever, and that if they listen to them and do exactly what they say, they will return it to the way it was when it left the Ferrari factory. I don't know if any of those people have ever seen cars that left the Ferrari factory, but the race cars were very primitive.

I remember Roger Penske telling a friend of mine, Alberto Pedretti, that he had just bought a brand new Ferrari 250LM, and that it was a used car and he was very angry. Enzo called Alberto and told him to go calm Roger down. And Alberto looked at it and said ‘Mr Penske, when Ferrari finishes a car, even if it is brand new, they take it out, they test it, they don't clean it and they send it to you. This is a new car, it's just that it's been tested.’ For someone who races in real races now, I completely understand what this means. We have race cars we built that have been crashed leaving the pits on their first outing. You pull parts off and you put on other parts and you swap body parts and then 20 years later at Pebble Beach someone claims that it is exactly as it left the factory...

Of the Ferrari “P” cars, the only one existing today that has its original chassis, engine, gearbox and original body, as it left the Ferrari factory, and a little bit of its original paint, is my 412P, the Maranello Concessionaires car. The reason is because when it still had the original body that had not been crashed, David Piper wanted to keep racing it, so he stripped it off, put it in his garden and built a fibreglass body that he raced the car in. Many years after David sold it, the owner of the 412P tracked down that original body and stuck it in his garage. When I bought the car, the owner casually mentioned that he still had the original body and asked whether I wanted it. So I began a painstaking restoration to save the original body, which had been corroded and had issues, and as much of the paint as we could, and I put it back on the car.

So 412P exists as chassis no. 0854 today; it is extremely original, but it's very rare because Piper even had a crash where the car caught on fire. Luckily only the fibreglass body burned so the original body wasn't destroyed, the engine and chassis and gearbox were fine and the car was racing six months later. If he hadn't stripped off the original body and left it in his garden, it would have been burned up and lost forever. The most original P4 existing, Lawrence Stroll's, is a magnificent car and it is very original, but it has a Spyder body on it, not the original coupe body that it had when it left the factory. Now that doesn't diminish its value in any way; it's a magnificent car that was changed by Ferrari in period to make it a better race car. I'm not in any way implying that if it had its original coupe body it would be more valuable or not, but I mean there are competition cars that I have seen at Pebble Beach where basically the only thing original in them is their chassis plate, and 100% of the rest of the car has been re-manufactured over the years.

SCG 003CS at the Villa d'Este 2015. Source: Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus

That's a very interesting insight - quite an eye-opener. Speaking of manufacturing, your application to the NHTSA to be a low-volume manufacturer was approved in 2017 and now Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus is a company which manufactures road cars and race cars, Le Mans Hypercars, and extreme off-road vehicles like the Boot which humiliated Ford by winning the Baja 1000 last year. What determines that huge breadth of interest for you?

When we began making road legal versions of race cars, we were doing that under a law which had been introduced by President Obama in 2015. However the legal landscape changed as time went on, so we met with NHTSA and agreed to meet all required Federal motor vehicle safety standards, crash test the cars and work with the EPA to get certifications for our engines, with the idea of operating under the regular manufacturers’ law. The low-volume manufacturer part simply refers to the fact that we manufacture up to 4,999 vehicles a year. So what we do now has nothing to do with the Obama law or the previous law that we made very few cars under. Our cars are fully compliant with emissions and US motor vehicle standards, as we're basically buying brand new emissions compliant engines from OEMs and installing them without modification into our vehicles.

SCG 004C testing. Credit: Hide Ishiura / Source: Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus

In doing all of this, I wanted to have basically two types of vehicle that we could sell for road use. One of them is our 004 which is my ultimate sports car. It's a three seater like the original Ferrari Agnelli three seater, which McLaren later copied in their F1. It's a mid-engined car, a homage to the Dino Competizione and also a 1986 Corvette show car called the Corvette Indy. It also has elements of many of the beautiful sports racers of the ‘60s and early ‘70s, and some parts of the Ferrari P4/5 by Pininfarina. We make both a road and a race version of it; the GT3 version has much more aero, a lot more horsepower (up to 840bhp versus 650bhp) and a paddle shift transmission. That is really as close to a GT3 car for the road that you can get.

SCG Boot is a modern high-performance homage to the Steve McQueen Baja Boot. Source: Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus

Then the second vehicle type we make is of course our Boot. A number of years ago I saw Steve McQueen's Baja Boot for auction at Pebble Beach. I was just astounded with the engineering of it. It turns out it was engineered by Vic Hinkey, who did the Lunar Rover, and he took the money he got from NASA and in the same room he built the Boot. I have a picture of them rolling the Lunar Rover out of that building with the Boot in the background. Steve McQueen found out about the Boot and he loved the Baja 1000 so they got it to him, and that vehicle raced for 14 years, beating the Bronco (only losing once in 1967). The Baja 1000 was the inspiration for the Mint 400, and the original Boot raced there when Hunter Thompson covered it in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

I love the Baja Boot and I knew we had to engineer a modern, road legal version of it. I was put in touch with Darren Skilton and he got Armada Engineering to help work out a road legal and yet Baja-capable version for us. The greatest thrill was driving that thing from Los Angeles down to Ensenada, racing the Baja 1000 and driving it home. It is the most fun thing to drive in the world. Going off-road in it is like deep powder skiing, and it has so much suspension travel that you float over bumps comfortably. On the roads, giant potholes mean nothing. So we're very excited about it. Our sports cars and race cars are engineered by Podium Advanced Technology, with whom I have worked for many years, and they are also building our Le Mans Hypercar. If we expand into Europe with our road-going sport cars and even our Boots, we may very well use Podium to build those over there.

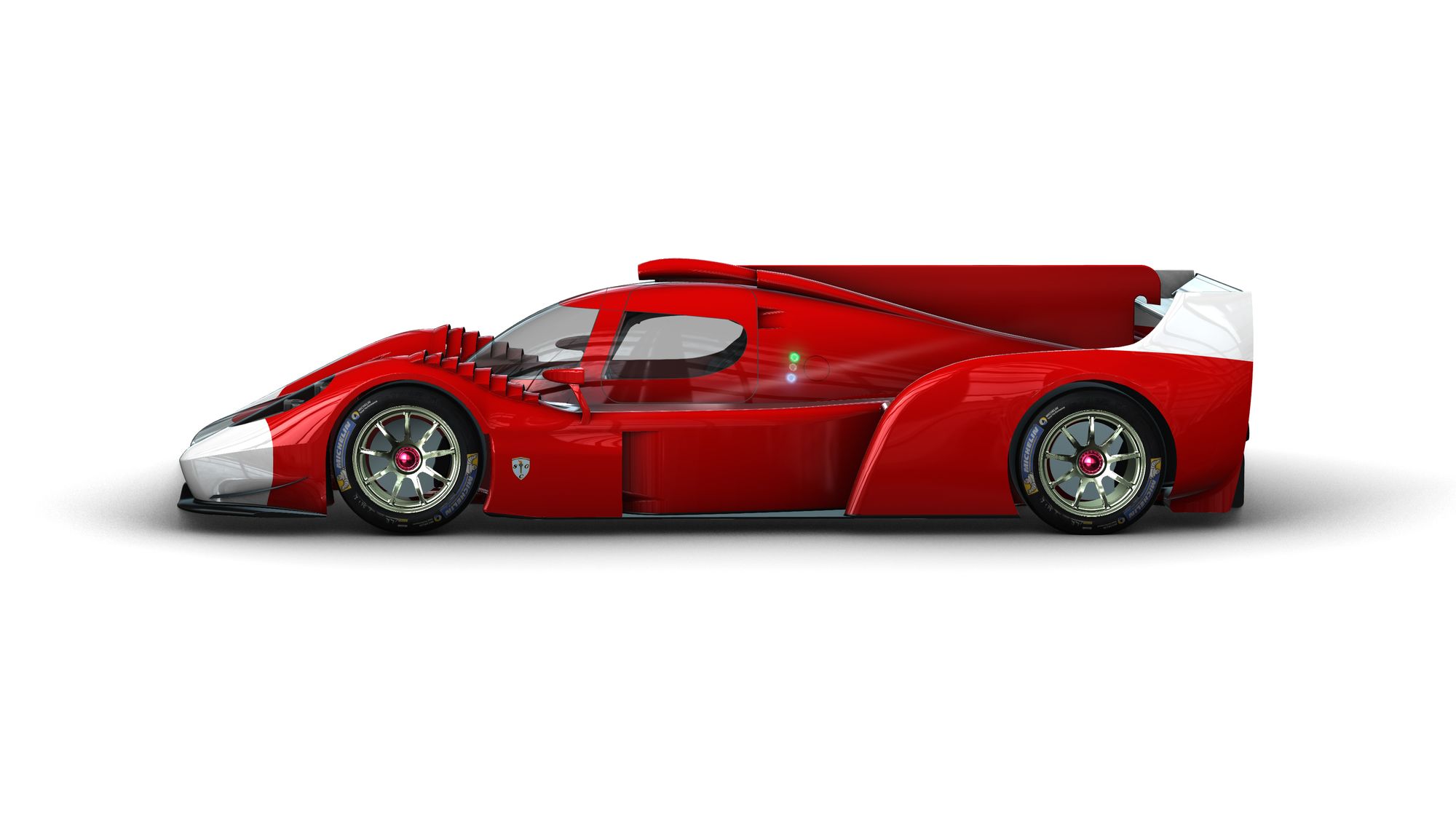

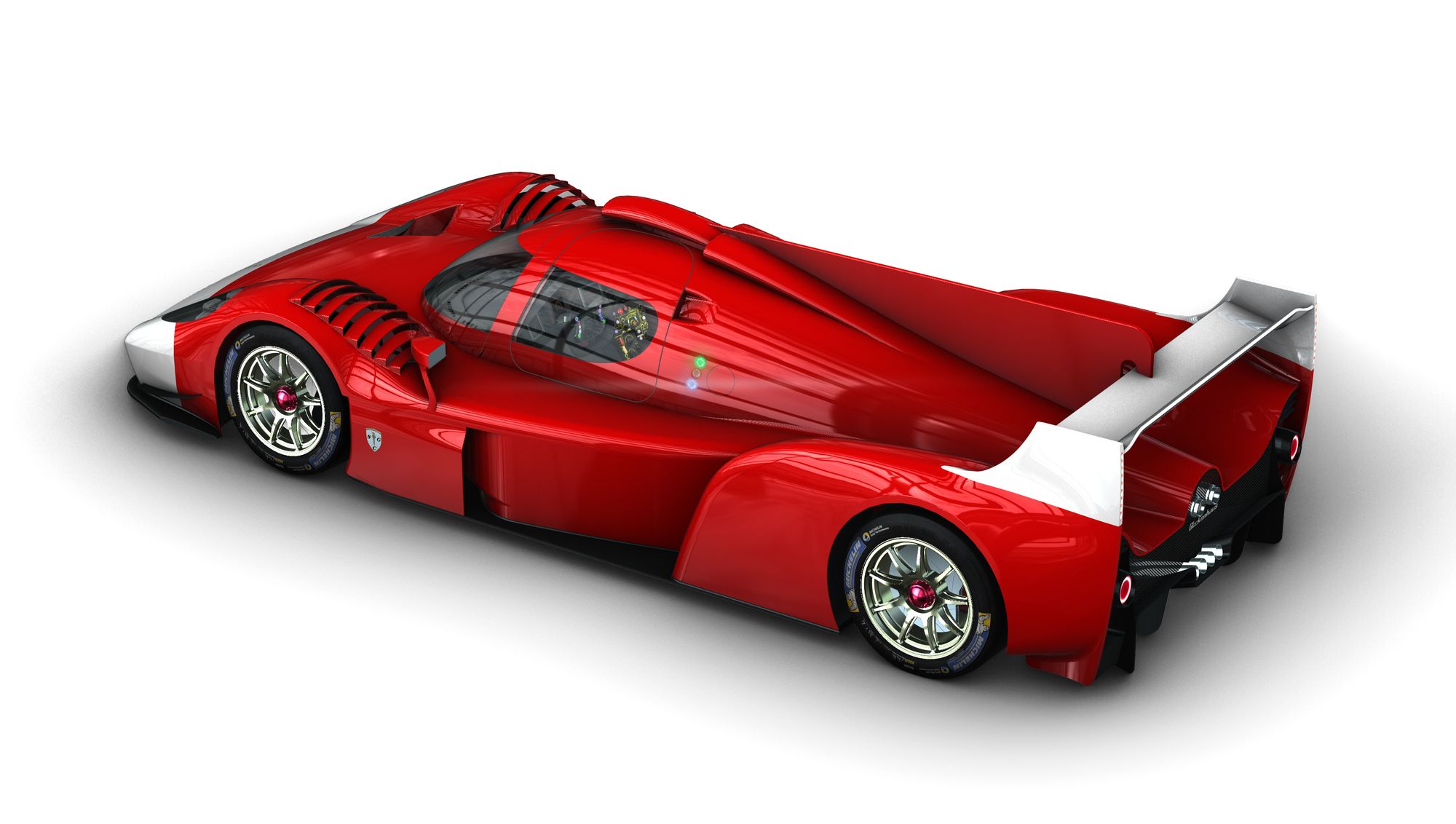

SCG 007, the Le Mans Hypercar. Source: Scuderia Cameron Glickenhaus

On the topic of Hypercars, I understand that you played a significant role in shaping the Le Mans Hypercar regulations, and Scuderia Glickenhaus is of course developing the 007 to race at Le Mans 2021. The last 12 months have shown that development can be a rocky road even for well-known sports car manufacturers, but you seem to have a drive to show up and fight that few other outfits have. Is Le Mans more than just a race for you, and what point does Scuderia Glickenhaus have to prove at Le Mans with the 007?

This is me going back to 1967, showing up and racing at Le Mans, and that's all. We have nothing to prove. I want to show up with a beautiful, fast car that has a chance of winning. That in and of itself is all I'm looking to do. The road here was a very rocky road indeed - the problems were caused by a lot of bizarre behaviour from companies like Aston Martin who said they would only race if the rules specified something like the Valkyrie and allowed for the Valkyrie V12, which was totally unsuited for racing. It’s a big, heavy engine so it's very hard to make an efficient LMP Hypercar out of it. We went along with it and because they knew that they couldn't get it very light, they wanted to raise the minimum weight and the maximum horsepower you could have. Then they pulled out, and so the only two real people who were left were Glickenhaus and Toyota.

It was a big problem for both of us. Toyota had finally reached a way to meet the 870bhp using a combination of a hybrid and an ICE, but we had thrown out our deal with Alfa Romeo because their engine could not make 870 HP in endurance tune. We eventually went with Pipo Moteurs, a fantastic engine builder making WRC engines that have been very successful for many years who had a vision of achieving that figure. Then we had to switch again to the lower rating of 670bhp, but we still had to find a way to make the cars fast enough.

The problem is the ACO, while they knew these would be slower than the current hybrid LMP1s, didn't want to slow them down too much because then they would be bumping into the LMP2s and then problems would arise down the food chain. So it was a massive amount of rule change, and a lot of money was wasted going down silly paths that later got changed, but we stuck with it.

And are you on track now to turn up with a beautiful car that, I think I've heard you say before, you can then drive home from Le Mans.

Exactly. We will actually have a two car team. We're doing our final aerodynamic testing this week and will have the engine on the dyno in early October. We will begin building up the car shortly after that and we will be at Sebring next year with two Glickenhaus 007 Le Mans Hypercars. We will race Sebring, Spa and Le Mans, and we hope we will continue racing after that, but so far as we know those are the only three races that have been scheduled for next year. We are sure they will schedule probably three more races, and we certainly hope to join that whole season, but we can't commit to something we don’t know the details of.

Our goal is to race at Le Mans against the giants, in this case Toyota, who certainly know a thing or two about Le Mans(!), and to have a car that is extremely competitive. It doesn't matter where we finish or what happens, just having been able to show up I think is a monumental achievement. More importantly, I think people are going to be shocked when they see how competitive we are. We have a really competitive engine, a top aerodynamic team working on it, and it's a pretty beautiful car. I think we'll stand and deliver.

I have to say that sounds very exciting, and I look forward to it. We're running up against time now, so I thought I'd just fire some quick fire questions at you to finish off. The first one is: what's the best car you've ever driven?

The most fun vehicle I've ever driven is actually our Boot. It's the most fun to drive because off road you can still go at these exciting, crazy speeds. Going 40 mph off road over giant bumps and floating through it all is just fantastic. The best sports car however... I really like the Dino Competizione. It's light, it's small, it is basically a mini P4. You can toss it around, and in the mountain roads of Sicily where I drove it in the Targa Florio, it was just an unforgettable experience. I also love the Ferrari P4/5 by Pininfarina. Again, I drove the Targa Florio in that car with my wife, and when we were driving in the rain in the mountains of Sicily, listening to opera, it was a pretty special experience.

Your favourite race circuit?

Probably the Nurburgring. I think it's the most like circuits were in the ‘60s. When the massive crowds are there, the 24 hours of Nurburgring is like Burning Man, Woodstock, James Hunt and Nikki Lauda and Stefan Bellof, and all of that rolled up together.

If you could choose any driver in the world to race your 007 to victory at Le Mans next year, who would it be?

We’re going to need seven drivers for our two cars, so I think we will have some really amazing people who we will test in January. Basically I want great drivers who understand the challenges of endurance racing and frankly will listen to what the team tells them to do, because it is not possible to win at Le Mans if you just go off on your own. You really have to have a lot of strategy for pits, for BOP, for managing the car, for not crashing it, and simply running lap after lap at the right speed. That’s how you can win. I think we're going to have a lot of skilled, interesting people who may want to come over and drive for us, and I really look forward to that.

And the last question: what's the greatest lesson you've learned from your time in motorsport and the car industry?

I think the greatest lesson is that there are wonderful days, and there are terrible days, and the key to success in my opinion is to keep on trying, not to let a failure break up your momentum, but to just keep going. If you show up and you keep going, you have a chance.

And on that bombshell, Jim - it's been an absolute pleasure to have you on with us today. Thank you so very much for your time and best of luck to Scuderia Glickenhaus in your upcoming races.

Thank you so much.