Enzo’s Revenge: The 1967 24 Hours of Daytona

It was late 1966, and Enzo Ferrari was not a happy man. Courtesy of the Ford Motor Company, he had suffered three defeats of the most painful kind at Daytona, Sebring, and Le Mans. After millions of dollars spent and numerous battles on the world’s most celebrated race circuits, the 1966 World Sportscar Championship trophy was firmly in the hands of Henry Ford II. Rumours were spreading that Ferrari’s decade of dominance in endurance racing was over, and morale at the Maranello factory was low. Given the pressures of producing sports car prototypes, Formula 1 cars, V12 production cars and more in the face of labour disputes and parts shortages, it was not at all clear that Ferrari could stage a fightback in the 1967 season. As the 24 Hours of Daytona loomed, there was just one question on the mind of motorsports fans: what would Enzo Ferrari do?

Written by Hector Kociak for The Apex by Private Collectors Club. Edited by Charles Clegg. Produced by Demir Ametov.

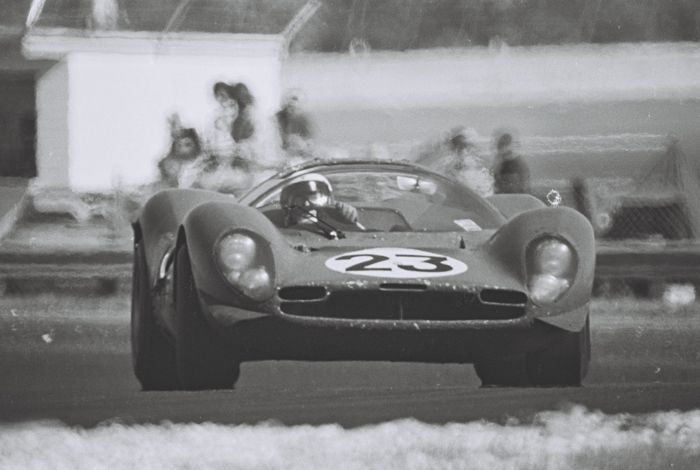

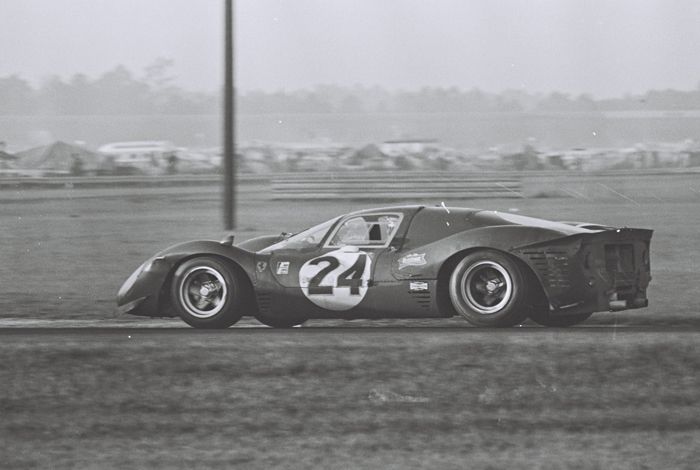

In retrospect, the answer was obvious. Ferrari would stand and fight. Technical Director Mauro Forgheri was told in no uncertain terms to take the 1966 P3 and make it better. The 330 P4 was the result, with a powerful new fuel-injected engine, a reworked gearbox to replace the flawed Tipo 593 ZF transmission, magnesium Campagnolo wheels and wider Firestone tyres. Ferrari recruited Chris Amon as a driver, who barely half a year prior had been on Ford’s winning Le Mans team, and a pair of new 330 P4s were flown to Daytona for testing just before Christmas. Test results came quickly, and were provocative: the P4s broke the Daytona Speedway track record set by Ken Miles for Ford during his victorious drive in the first edition of the 24 Hours of Daytona in 1966.

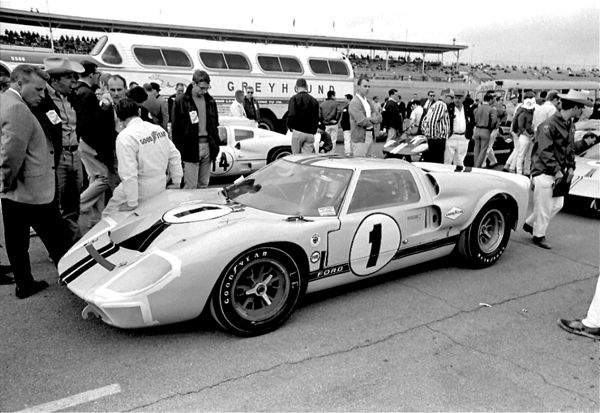

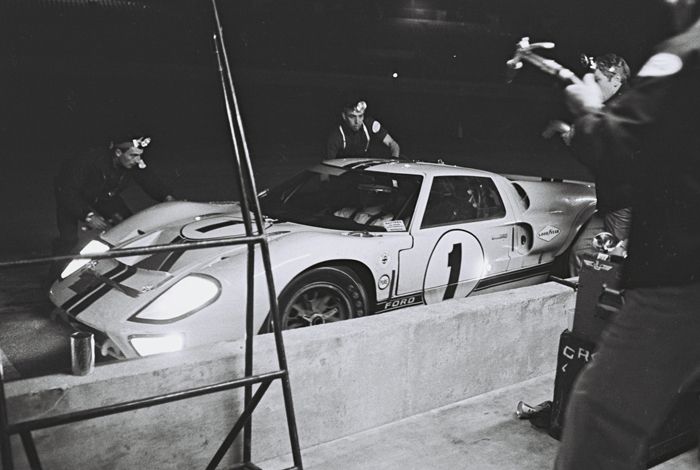

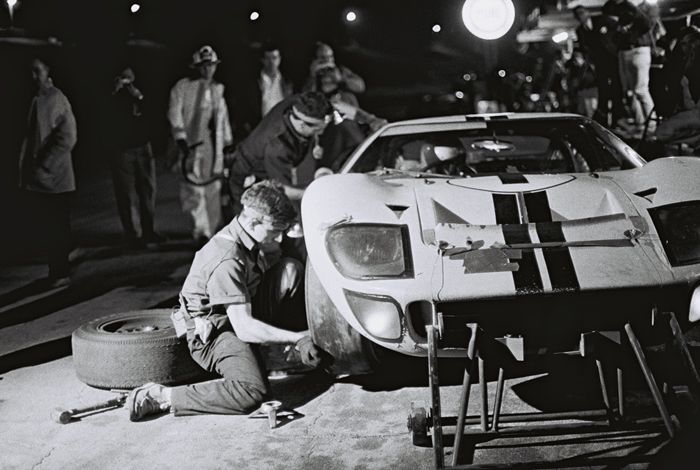

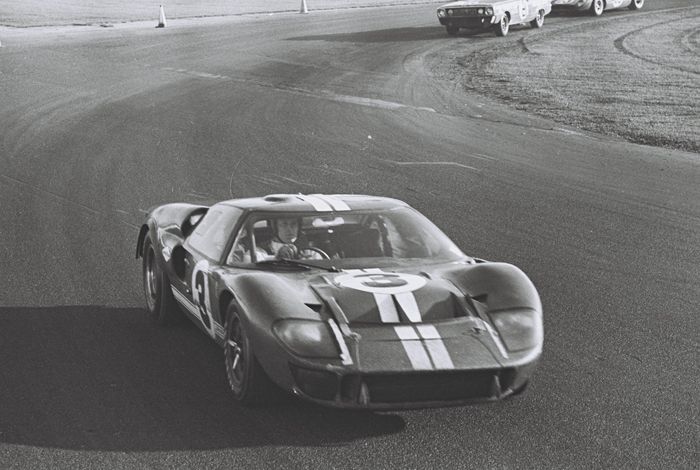

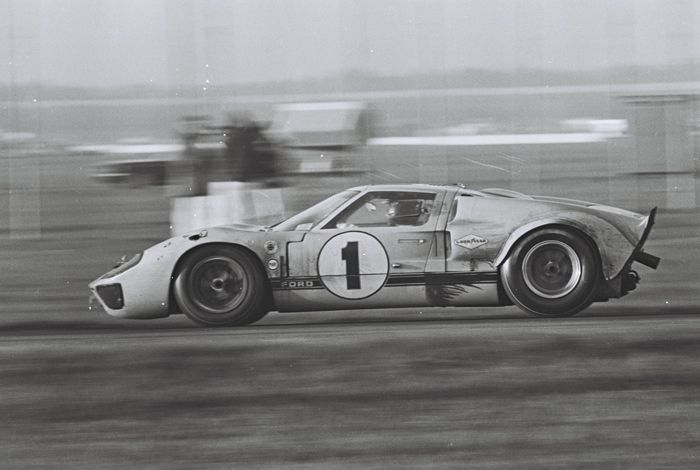

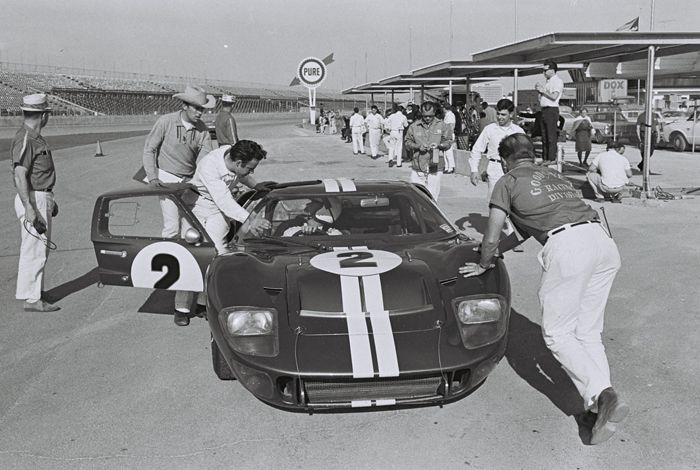

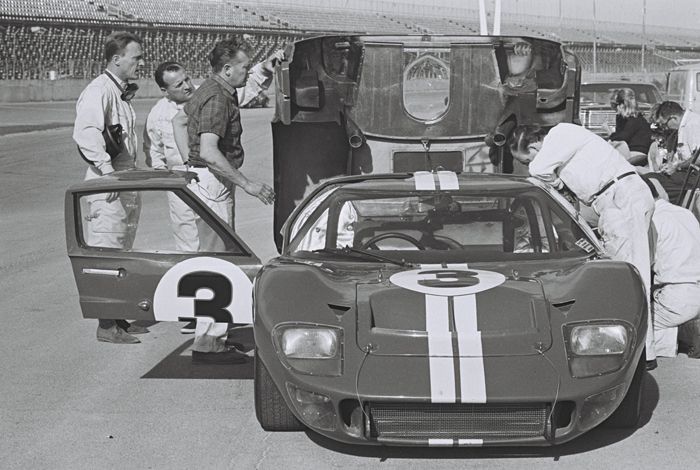

The impressive Ferrari performances caused some concerns at Ford, compounded by poor performance of Ford’s third-generation “J” cars during testing at Daytona. With the “J” prototypes deemed unsuitable for deployment, the older Ford GT Mk IIs were the only option left for the 1967 race. No expense was spared to make the six Mk II prototypes flown to Daytona by Ford Advanced Vehicles competitive, however their powerful 7.0l 530hp engines, sturdy T-44 transmissions and heavy roll cages came at a price: enormous weight. It was suggested at the time that each Mk II weighed over 200kg more than the equivalent P4, and despite an opulent Ford setup with an army of mechanics which dwarfed the less pretentious Ferrari effort, there were soon rumblings that fielding such heavy, powerful cars could cause problems over the course of the race.

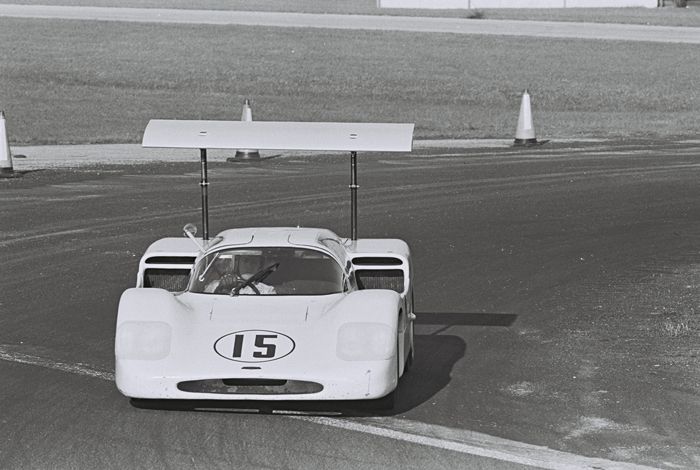

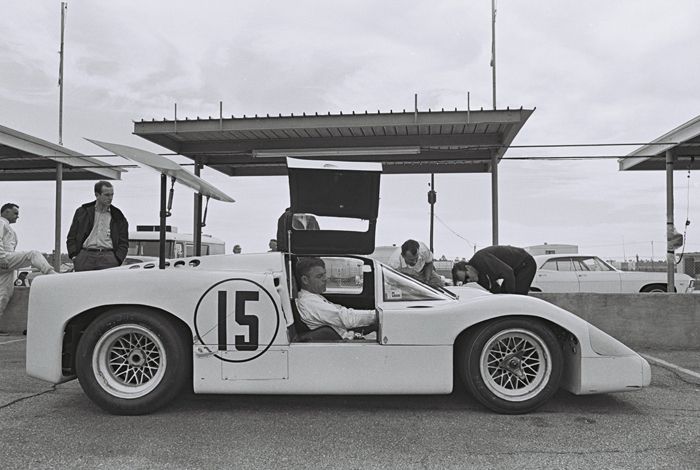

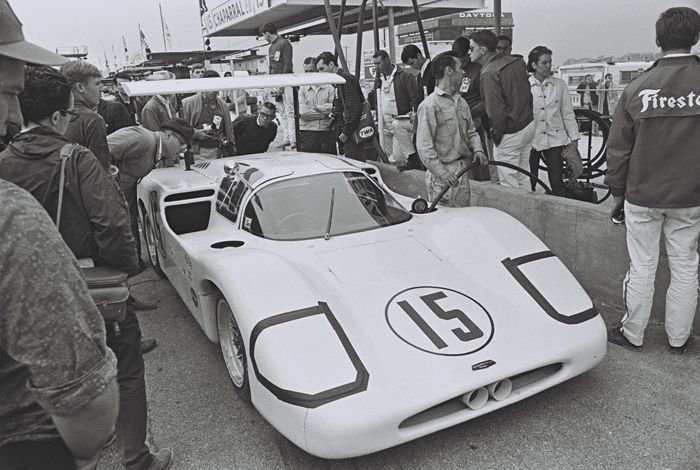

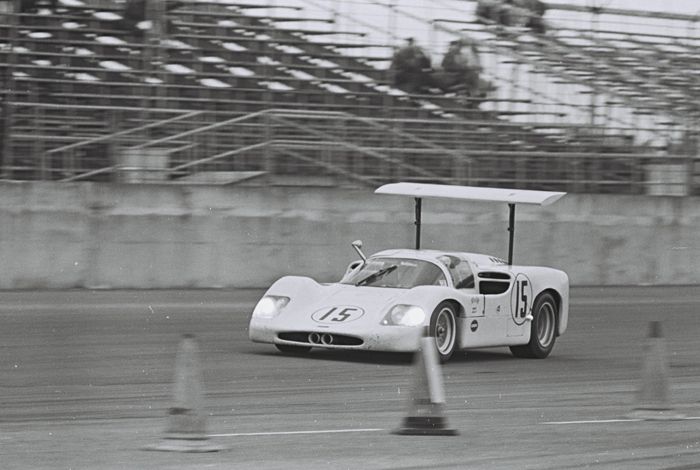

In qualifying, Dan Gurney and A.J. Foyt took pole position (just about) in their sprint-configured Ford GT Mk II - although the advantage of 0.26 seconds came at the price of a set of slick tyres and an engine replacement. Phil Hill’s Chaparral 2F (replete with curious aerodynamic wing) put in an excellent qualifying performance to take second on the grid. The Amon/Bandini factory Ferrari P4 could only muster 4th place, behind the surprisingly fast NART Ferrari 330 P3/4.

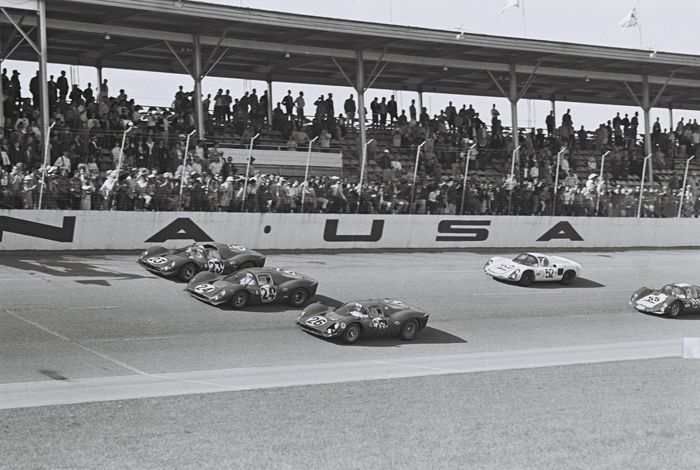

When the green flag fell, Hill’s Chaparral 2F quickly took the lead, leaving the Andretti/Ginther ‘rabbit’ GT Mk II (whose original task had been to push competing Ferraris and Chaparrals beyond breaking point) lingering behind. A slow trickle of Ford pit stops began soon afterwards. When the leading 2F crashed out of the lead about three hours into the race after losing control on a section of loose asphalt, it was not a Ford which took the lead. It was a Ferrari.

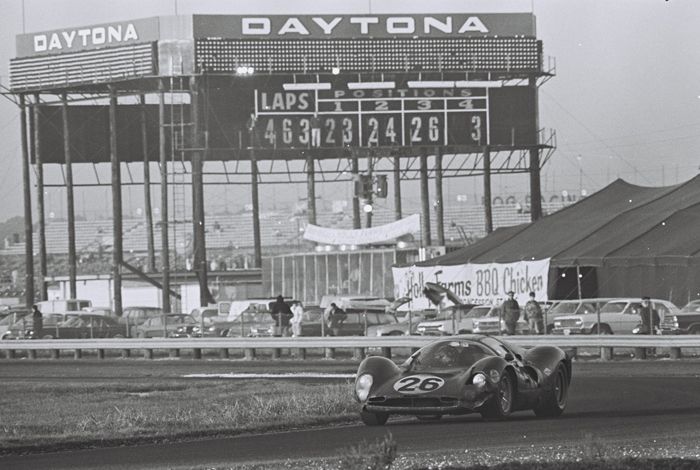

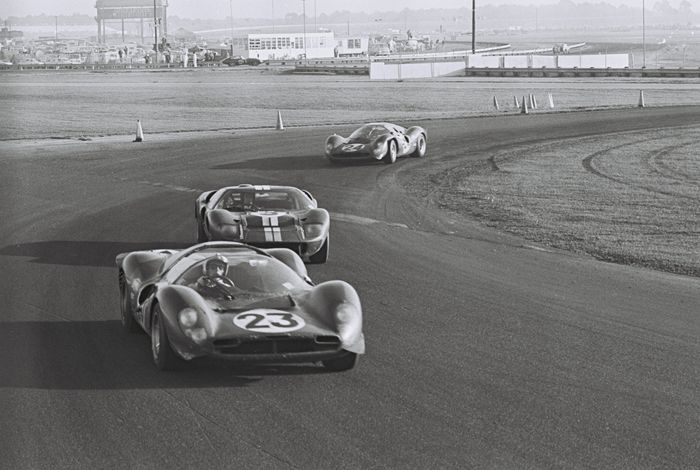

Under the watchful eye of team manager Franco Lini, Ferrari had played a patient game early on of sticking to target lap times and waiting for the attrition of the rest of the field. As the Chaparral 2F span out of contention, the Amon/Bandini and Parkes/Scarfiotti P4s were there to take advantage. They would not relinquish the lead for the rest of the race. Meanwhile, the struggles of the Fords continued. Their increasingly frequent visits to the pits began to attract the interest of the sports media present, and before long it was widely known that gasket failures and faulty transaxle input shafts were plaguing the Ford cars.

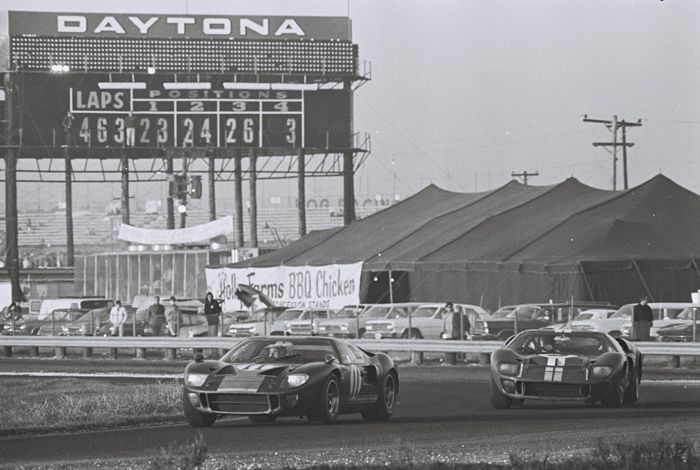

Fighting into the night, Ford mechanics replaced failing transmissions and conducted extensive repairs on a number of the Mk IIs. This only delayed the inevitable retirements. An engine failure took out the Gurney/Foyt Mk II after 464 laps; the McLaren/Bianchi car continued as the sole remaining Ford GT, occasionally overheating and no longer a serious contender.

While in the Ford pits the mood was one of despair, there was also a sense of justice being done, and not only amongst the fans of the Cavallino Rampante. As a Motor Sport Magazine report of the time put it, “the general opinion among the Americans seemed to be that the defeat could only do good as some members of the works team were under the impression that they were now invincible…”

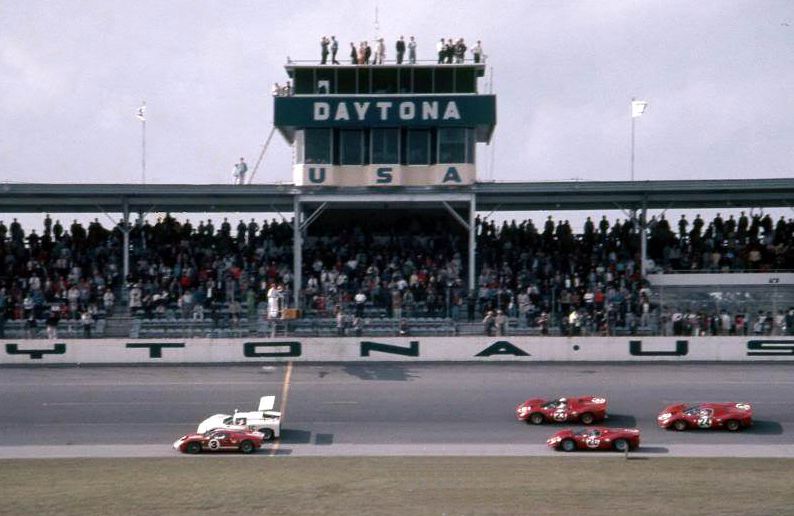

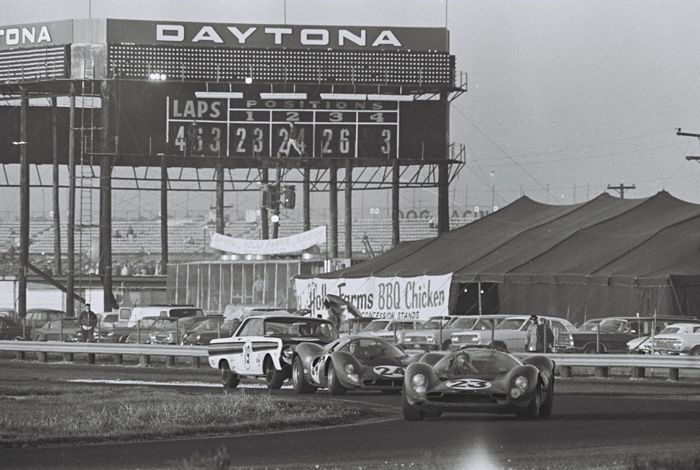

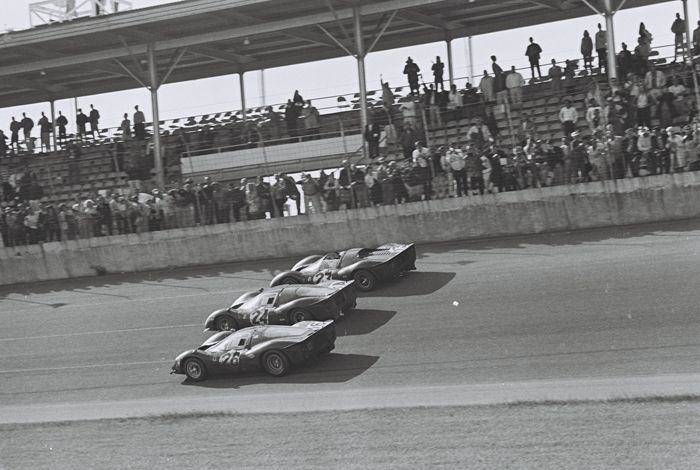

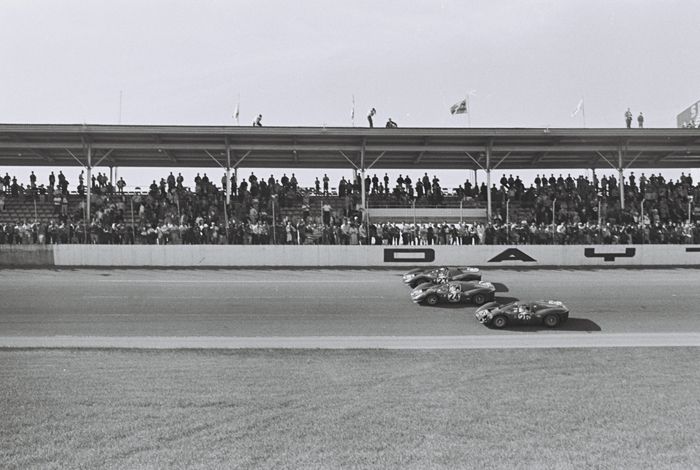

As news of the disastrous Ford stoppages reached the Ferrari pits, the order was given for drivers to nurse their cars through to the end of the race. After leading for almost 20 of the 24 hours of the race, the pair of factory Ferrari P4s led by the Bandini/Amon car, and followed by the Rodriguez/Guichet NART P3/4, crossed the finish line three abreast, revving their engines in celebration. This was a Ferrari comeback which would make history, so much so that Mike Parkes commissioned a painting of the 1-2-3 finish and presented it to Enzo Ferrari soon afterwards. Despite defeats in later years at the hands of the Ford Motor Company, Il Commendatore would keep the Daytona portrait on the wall of his office until his death in 1988: a proud reminder of a race in which David had managed to give Goliath one hell of a kicking.

Photographs below courtesy of the Dave Friedman Collection held at the Benson Ford Research Center - https://www.thehenryford.org/collections-and-research/.

The Chaparral 2F Driven by Phil Hill & Mike Spence

Phil Hill

The Victorious Ferraris

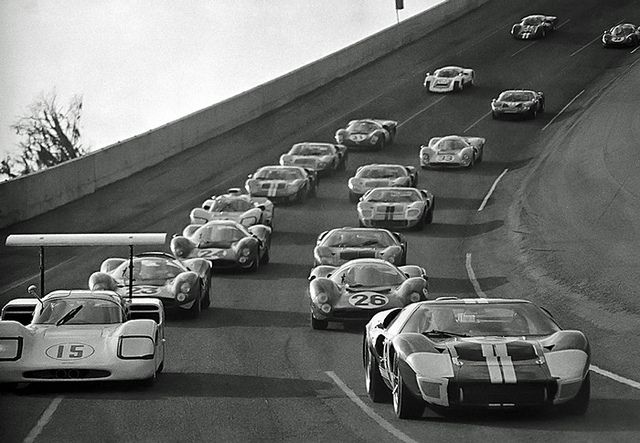

The Fords

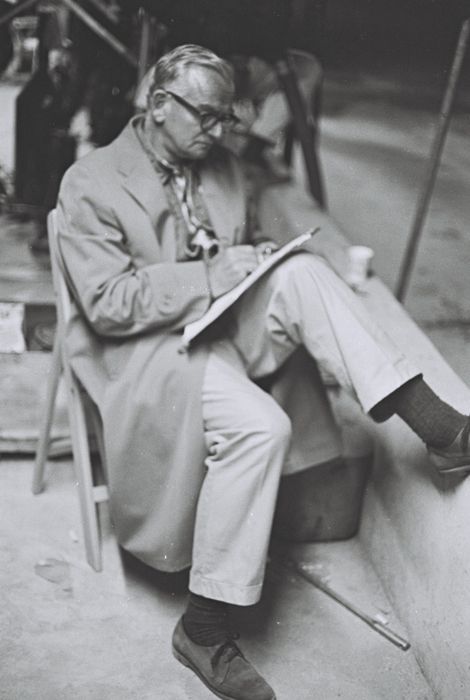

Behind the Scenes

The Ferrari 1-2-3 Finish

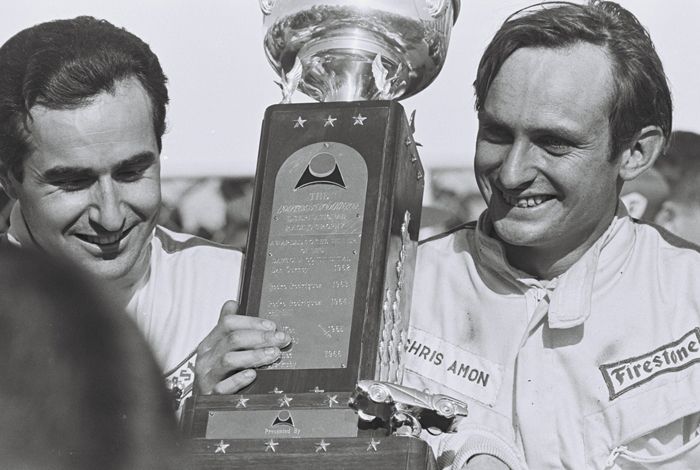

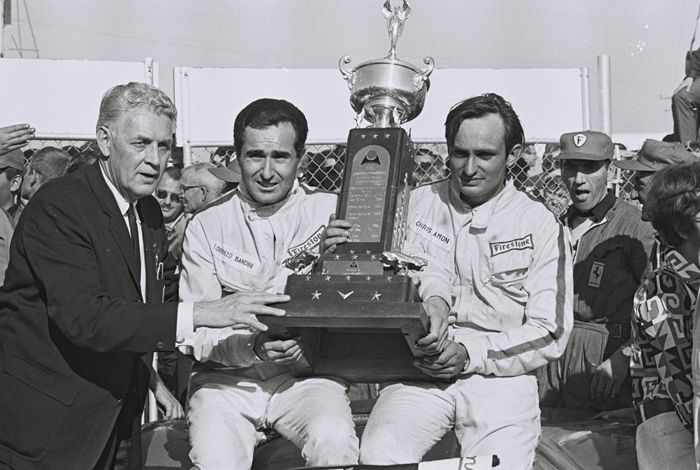

Prize Giving