Heavy Metal: The Apex Interviews David Brown

Our guest this week is prolific entrepreneur, businessman, and car guy David Brown. Proudly drawing on Britain's automotive heritage, his car company David Brown Automotive has grown significantly since its founding in 2013 and now works with over 70 British based suppliers, combining small scale manufacturing with a bespoke coach building to produce limited edition automobiles for discerning clients.

We managed to catch David for a discussion about his career, love of cars, and some of the exciting machines handbuilt by David Brown Automotive, including the beautiful Speedback GT.

Hector Kociak interviews David Brown for The Apex by Custodian. Recorded and produced by Jeremy Hindle and Guillaume Campos. Transcribed by David Marcus. Edited by Hector Kociak & Charles Clegg.

Could you tell us a bit about your early years, and your first automotive experiences?

No problem. I was born in Yorkshire to a family of timber leaders, meaning someone who cuts trees down and takes them to a sawmill. So right from an early age I was being told not to touch things, not to go anywhere near things, and it was all dangerous! The family's operation was based here in Yorkshire and was all about the use of machinery, so from an early age I watched my father use it all. He became a great designer and started many businesses. But he was also very much a driver, and my early memories are of being frightened to death by cars which, by today's standards, were awful!

He went on the Monte Carlo Rally a couple of times, when it was a proper rally. I think he started in Scotland, and they all met up somewhere around Paris from different points in Europe and then headed off to Monte Carlo. So there were always special cars in the family arsenal, from as far back as I can remember. I grew up with both an engineering background from age nothing, to a love of cars that always came from my father.

David with his company's creation, the Speedback GT. Source: David Brown Automotive

Before we get to the modern day and your car exploits, could you tell us a bit more about your family history, and the engineering and business environment that you grew up in?

As I mentioned, my father would go into a forest, chop trees down, and take them to a sawmill. Every element of that was a learning experience for everybody involved in it. When I was about five or six he got a job as a designer, and he designed himself a crane to work in forests. He exhibited the crane at what’s now called the Great Yorkshire Show, and was immediately offered a job as an engineer in a manufacturing company in Leeds. So he went to work there and he designed a few revolutionary things, because he had no training as a draughtsman or as a designer, but he had practical experience.

He was brilliant at being able to see something on paper in three dimensions, and envisage how it all worked together. This was in the days when everything was just drawn out, and you had to imagine how it was all going to fit together. He was very successful at that, and was eventually poached by another company building earth moving equipment in Blackburn. That company was called Shayside; it was bought by JCB and became the backbone of some of their products as they went forward. He then worked for other companies, including Muir-Hill in Gloucester. So I grew up not in Yorkshire but actually in the Cotswolds. That company manufactured earth moving machines, agricultural tractors and military vehicles, and they all came from concepts and ideas that my father had.

While he was doing that, I was busy being a singer in a rock band (!) and as far as I was concerned, that's where my future lay. It was going to be me and Roger Daltrey together on stage somewhere in Los Angeles...after a little while my father decided to start his own business. At the time one of the best places to do that was in the North-east of England, with all the development grants available. I didn't want to move to the North-east - I wanted to stay being a rock star. He said no problem - you stay and find somewhere to live, because we're off! I couldn't find anywhere to live, so I eventually moved to a place called Peterlee in County Durham. That's where we started the engineering company that built earth moving vehicles.

That company had a revolutionary design, an articulated off-highway dump truck. They're the sort of things you see now literally all over the world, the wheel barrow of the construction site. We ended up selling those vehicles everywhere and designing all sorts of things. It was fascinating, because the vehicles got used in all sorts of different applications and different places. We built vehicles to go down the Kiruna mine in Finland - one of the deepest mines in the world, where the excavators would have to descend very far before coming back up. In Iran we built some vehicles with a pivoting cab for a breakwater project with narrow access which you could only reverse down, so that the driver could literally turn around backwards and drive more easily with a reversible steering system. In each case there were lots of different things that you had to think about within the concept of the actual vehicle itself.

The other side of that business which is relevant to my car company is the manufacturing processes. We were always the first to buy something really new - for example, plasma burners. A plasma burner cuts steel at relatively cold temperatures. Consequently, you don't get any distortion in the steel, and when you can do that, you can then design things in a different way to take advantage of that particular part of the manufacturing process. So all the time we were at the forefront of technology, as far as machinery was concerned. We were always experimenting with new things, and that always ultimately led to an improvement in the way you could make things.

The David Brown Automotive showroom located in the St John’s Wood area next to Lords Cricket Ground and Regent’s Park. Source: Media World Digital

I can see how that would translate to making cars! After you left that company, you had a string of other businesses as well - so I guess that the manufacturing and business knowledge all led quite neatly to David Brown Automotive itself. What was the inspiration for that particular company?

At one stage I owned a DB5, which I thought I had to buy because it's got my name on the front of it somewhere! I really liked the car - it was one that had been converted at some point to a racing DB5, and so it still had quite a few of those features left on it. You could chuck it in a corner, the limited slip diff would kick in, and you could slide it around the bend. It was fun.

But - and it's a big but - it was massively unreliable. At one stage after a trip out one day, I remember waiting for the AA to recover me because the top hose had burst. If it wasn't the top hose, it would be an electrical problem, and so on. I thought is was ridiculous - I'm going to re-engine this thing. I spoke to a few friends and they said: you can't re-engine that, you'll destroy it entirely! So I decided I would make a car that was synonymous with all the things I liked from the ‘60s, and that's basically where the Speedback GT came from.

A lot of people would say to me, well, how do you actually go about making a car? Funnily enough I never considered that a problem, because of all the experiences of making things previously and owning businesses. When I eventually took over in my father’s earth moving equipment company, I eventually sold it to Caterpillar. When I did that, I bought a whole series of other businesses, largely lifestyle related. I had mens & ladies’ clothes shops, a ladies’ shoe store chain… I actually won an award for having the best department store in the UK, shared with Selfridge’s - I was quite proud of that!

As part of the more lifestyle part of the David Brown brand, the Speedback GT featuring the Arnold and Son Tourbillon Chronomoter no.36. Source: David Brown Automotive

The long and short of it is that I had a lot of experience in the lifestyle side of business too. On the earth moving side, if you went to a show, it was normally in a quarry(!). Collecting an award for a fashion brand was a completely different environment, but it all combined with the manufacturing experience. I also kept myself in touch with the technology that was being developed over the years. One of the biggest things by far was the digitisation of information. I remember seeing a friend who had made a pedal box for his car using a 5-axis CNC milling machine. This pedal box was beautiful. It was hidden by the way - you couldn't see it once it was in - but it was gorgeous, and I just thought, hell, you can make things now that you couldn't have made years ago.

When we started to make the Speedback, the initial way of doing that was to make a rolling chassis. If you think about the days when Rolls-Royce or Bentley made cars, they didn't make a complete car; they made a rolling chassis and somebody else put the bodywork on top of that. Mulliner, Park Ward, and all those famous names from the past had done it, and I wanted to be able to do the same, not to have to reinvent everything. I had seen plenty of people make their own engines, for example, and just have it bankrupt them. But it made sense to use componentry that already existed. So I started to make the Speedback GT using a rolling chassis from the Jaguar XKR, because everything about it was just right. Even the way in which it was manufactured, with a series of bonded aluminium parts that we could use and join our pieces to, made creating the complete car easier. It also had something I really wanted, which was a British V8 engine, which we could use to make a genuine GT.

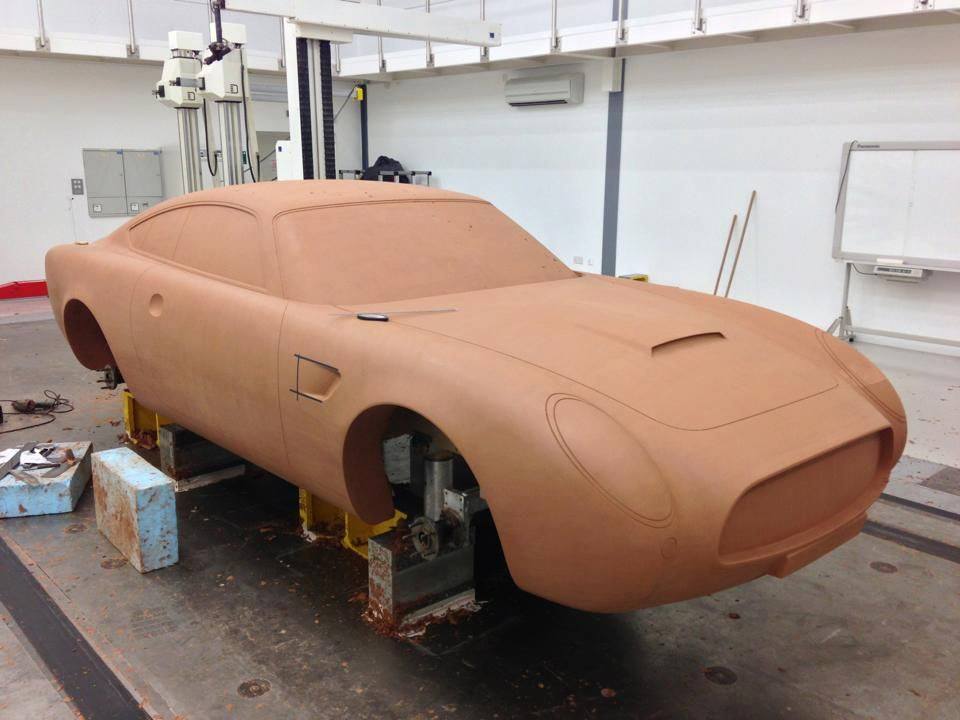

Using that we made a clay model of the entire car at full size, to get the styling cues in there. The cues we used were everything from the ‘60s. When we went into the styling studio, we had no pictures of cars, but we had pictures of lifestyle things from that period, one of which was Sophia Loren lying on a sunbed! If you want some inspiration for curves, you can get it by looking at that. We also played rock music from the period, and I'm not sure what we drank, but we drank some ‘60s stuff as well…

The original clay model of the Speedback GT. Source: David Brown Automotive

It sounds like complete immersion!

It was! The 1960s were probably one of the most interesting periods in our contemporary history, in that the ‘50s were a diabolical era. Britain was poor, and couldn't even feed itself, let alone design something really sexy. Then the ‘60s came along and suddenly there was more money, but there was also social liberation. So music changed totally, art changed, sex changed, style changed, everything did. Some of today's most valuable classic cars come from that period of time, and I think it’s because they're actually the most beautiful and unconstrained forms. That's how we came up with the style of the Speedback GT. People will say it looks like a DB5 - well, first of all, thank you very much, but it doesn't. If you see the two side-by-side, it really depends on your frame of reference. Italians might see it as having a 250 SWB look and a Maserati front. Germans friends have seen it as a Porsche, and Americans see the backend as a muscle car.

In my mind it is not a pastiche of different things; it is complete in its own right. In that sense, we have a vehicle that reflects a lot of the characteristics of the ‘60s, but on a contemporary chassis with all of the modern facilities and features that you would expect in a car from today. With the clay model we actually made two sides, subtly different and decided which one we liked the most. Then this is where digitization comes in. The clay model was scanned and the half of the car that we liked was mirrored and flipped onto the other side. Every square millimetre of that car is recorded in that digital file. The same information then gets used by a 5 axis CNC milling machine to create the hammer forms, which a man on an English wheel (with a skill that I'm delighted the UK has still got) uses to shape a metal panel. So with that you get a gigantic amount of accuracy.

If you look at some of the cars of the past with bodies shaped on an English wheel, the two halves of the car would be different because they're entirely handmade. Whoever was styling the DB5 in Italy (Carrozzeria Touring) would be looking at photographs of Sophia Loren, and creating the clay model by hand. Somebody would then measure that clay model and produce the hammer forms using old-fashioned carpentry skills. With the best will in the world, there were always going to be mistakes! One side was absolutely not going to be the same as the other, you’d have panel gaps and so on. The digital process gets rid of that problem.

A closer look at the David Brown Speedback GT. Source: David Brown Automotive

How easy is it to do all of this in a modern context as a small scale British manufacturer? What are the keys to success if you're a small manufacturing company and you need to find the right people, the right knowledge, even the right tooling?

I think there's a gigantic difference between what we do and more mass-produced cars which is often not appreciated. Our Speedback GT will sit side by side with a contemporary high-volume car, and the way those two vehicles are made is hugely different. If you can be sure you are going to get a high production volume, then you literally tool up in a different way. You can press a part, stamp it out in metal, and it's done. The cost of that tooling is enormous, but the piece cost is much less, because the piece costs don’t include skilled labour. The UK is great in that it's coach building history has never really fizzled out, so it has a reputation and the skills for the manual process to this day. With all due respect, the English wheel is not called the French or the German wheel! It’s a bit of technology that is just two large round metal bits touching each other, used to shape metal and to build stagecoaches in the past.

What I really like about what we do is that we use a combination of those traditional skills alongside digital processes. That gives accuracy but also beauty, because you can create things on a 5-axis CNC milling machine you could never otherwise have done as a small manufacturer. Our cars are handmade as opposed to hand-finished. We will take an aluminium ingot and we will shape that into the part it will become on the car. We can still make things in volume, but they will be more expensive because of that.

Source: David Brown Automotive

So tell us a bit about your customers. It must be quite an interesting mix of people?

It is. There are quite a few people like me, who own classic cars or have had classic cars, and loved them because they're beautiful, but also know that they're not particularly reliable. Depending on what they want to do with the car, it means that they want something that has that ‘60s DNA, but with a reliable set of components that you don't have to worry about. Most Speedback GT owners will use their cars on a daily basis. If they have the classic equivalent, a Ferrari, Aston Martin, or Lamborghini from that period, most of them would only do it if they had an AA van following behind! They're all appreciative and knowledgeable people. I would say we're friends with all of them. They just get what we're doing, and why it is so different. They want a mercurial car, something that is largely different to anything that their next door neighbour might have. They admire what we do. We get a lot of credibility for being this British manufacturer of beautiful things, with a lot of British components.

Source: David Brown Automotive

I know that you've collected quite a few classic cars in your time - but I also know that you were once a competitive rally driver. Is that correct?

Yes indeed, I used to rally in the ‘80s and ‘90s in a Subaru in the UK, and I won the Group N championship in one. Then I decided to build myself a car, so I built a WRC car using Ford Escort components and it was bloody excellent. That was a Ford Puma four-wheel-drive with a sequential box. Even if I didn't win rallies in it, I used to win prizes for the scariest, loudest thing going down a forest track at 3AM, which was pleasing!

I love this combination of classic cars, coachbuilding, and just thrashing a Ford Puma with WRC bits in it down a forest track. It sounds like you've really covered off all the bases...

The other thing I've started to do is endurance rallies, which are a different thing altogether. For example Peking to Paris, which is a hell of a long way in a 1927 Rolls Royce Phantom II. I did it with a friend of mine, and it broke down constantly. Every single solitary day, something went wrong with it. To be honest, it wasn't actually the original parts of that car - it was the parts that had been added on over the years which caused the problems. It was amazing, but those things are called endurance rallies for a very good reason: you have to endure your navigator!

That's more of an adventure really, whereas the stage rallies were very competitive and challenging. When I used to do those, I would get to the start of the first stage, and it would be 6am in Dalby Forest or something. It was always freezing cold, and the rest of the drivers were either being sick from nerves or having a wee in the trees! The early starts never did me any good, because in the first stages the others were always quicker than me. It used to take bloody ages for me to catch up. It was all because I didn't wind myself up at the beginning, and I had to do it slowly throughout the course of the day...

Hah, that’s some performance advice! We’re coming up on time, so I've got three quick fire questions to end with. The first one is: what vehicles have inspired you most in your career?

There's a few. Some of the earth moving equipment that we built was fantastic. You’d have stuff that weighed 100 tons and would go across the quarry floor at 45 MPH with unbelievable suspension, brakes, and so on. The other car that inspired me is the Mini; we haven't talked about my Mini Remastered. That was something we wanted to produce to give the company more volume. The Mini was also my first car; the person I call one of my heroes, my father, used to describe the Mini as the best engineered car ever, and the worst manufactured car ever!

We decided we could do a great job of ‘re-manufacturing’ it, remastering it in other words. The original is a marvel of engineering. It came from the ‘50s, this period of destitution, as a cheap family car. We get to the ‘60s and suddenly it's a trendy thing! It broke down class barriers too, so you would get a worker at British Leyland driving one and you would get Lord Snowden driving one. It was a fashion statement, and then it also became a great rally car. It’s one of the most inspiring cars ever. I think our version of it and what we do with it is also absolutely superb. You look at it and you smile, you get out of it and you're still smiling. It's one of those things that just invokes sheer pleasure, for a whole multitude of reasons. So yes, I guess that was one of the most influential cars of my lifetime.

The Mini Remastered #012 inspired by Café Racers. Source: David Brown Automotive

Second question: do you still have a dream car that you are chasing?

No, not really, in the sense that the dream cars in many respects are clearly the ones that I make. I make them, and I've got them, so I've got that dream! I'm fascinated by other bits of technology however, and seeing where electric car design will go. At the moment I do like the new Hyundai and Kia cars that have just come out, the Ioniq 5 and the EV6. I admire them because they started design-wise from a completely different place to everybody else, and I am fascinated to see where that will all go with technology that will just do so much for us.

That's a common thread with some of the designers we've had on, who were excited about what people will do with these new drivetrains, and how you can design electric cars that are just a bit different, but still fun and engaging.

Yes, it's funny because we've got some people who bought our Mini Remastered, and they all said that they were going to use it to teach their children to drive, because if they can drive that, they can drive anything. It’s because it's got no electronic bits to help you - however, there will be a generation one day that couldn't possibly drive something like that, because there will be cars that literally drive for them! It does fascinate me.

Some more tasteful details of the Mini Remastered. Source: David Brown Automotive

Speaking of future generations, my last quick fire question is: what's the greatest lesson you've learned in your life, both as an entrepreneur and a car maker?

My greatest lesson in life is that nothing is ever quite as good or as bad as it first seems to be. I think in this world of almost immediate responses and instant e-mails, instant WhatsApps and so on, sometimes there is nothing better than just taking a step back and reflecting before you make your next lunatic decision...

I think that's a wonderful note to end on. David, thank you so much for joining us today, that was a really fun interview.

My pleasure, thanks very much for having me!

To find out more about David and David Brown Automotive you can visit their website at https://www.davidbrownautomotive.com/ or follow them on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/davidbrownautomotive/.