Covered Tracks: The UK’s Lost Racing Circuits

Until recently, it was easy to take spectating at a racing circuit for granted. Who among us thought that marvelling at the wind-blasted desolation of Silverstone, or sneaking into the forest at Brands Hatch to try to get an unconventional view of Dingle Dell, would become treasured memories of better times? Part of the joy of being a motorsports spectator is taking in the physicality of the competition and attending the venue itself - whether it’s twiddling your moustache and cutting a dash at the Goodwood starting line, fighting the deckchair brigade at Oulton Park, or just enjoying all four seasons at once up at Knockhill...

Of course Goodwood, a sacred site to many in the classic racing community, itself narrowly avoided permanent absence of spectators after 1966. The original 1948 circuit, born from what had been the perimeter of RAF Westhampnett, was by then no longer safe for modern racing cars. While vehicle testing continued, a general reluctance to change the fabric of the track meant that it was only in 1998, after a painstaking historical restoration, that the first Goodwood Revival could be held to celebrate Goodwood’s post-war golden era of sports car racing. 50 years to the day since the Goodwood Motor Circuit was opened, the present Earl of March drove the inaugural lap in the same Bristol 400 sports car that his grandfather had used at the original 1948 opening ceremony.

As the preparations for Goodwood SpeedWeek step up a gear, with the historic track using a remote-viewing format for the first (and hopefully only) time, The Apex team has stepped away from crank-starting our livestreams and oiling our monitors to remind ourselves of some of the more interesting UK racing venues which have passed into history. Whether you consider them to be historical curiosities or evidence of a sinister plot to deprive the public of fast cars, they serve as a reminder of how important it is to make the most of our motorsport heritage while we can - a sentiment particularly appropriate in these strange times.

Written by Hector Kociak for The Apex by Private Collectors Club. Edited by Charles Clegg. Produced by Demir Ametov.

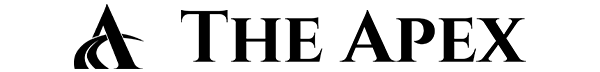

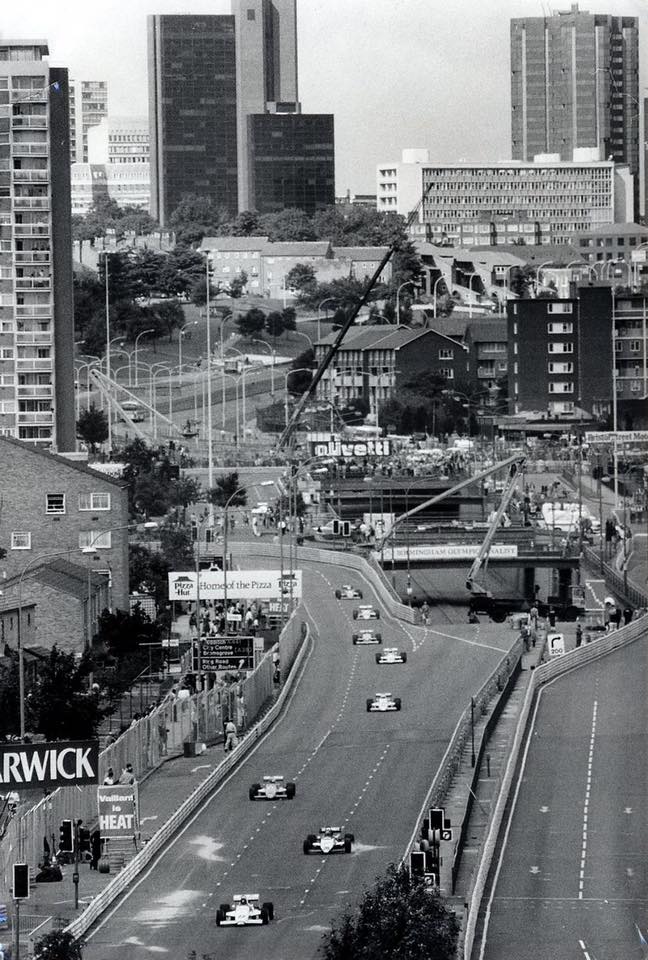

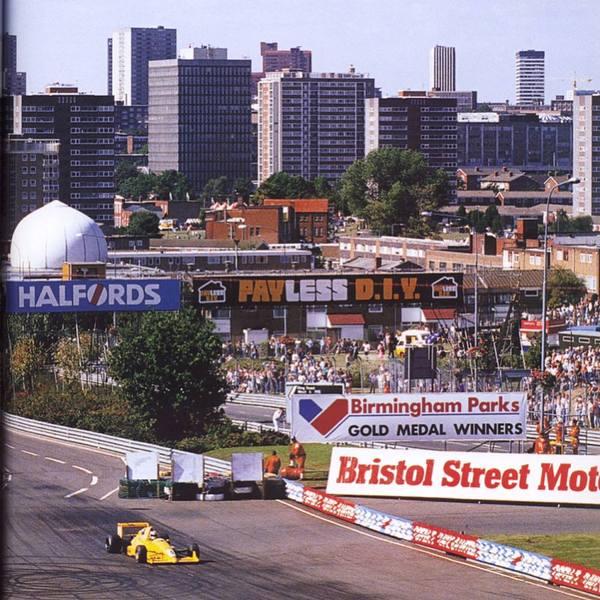

The Birmingham Superprix

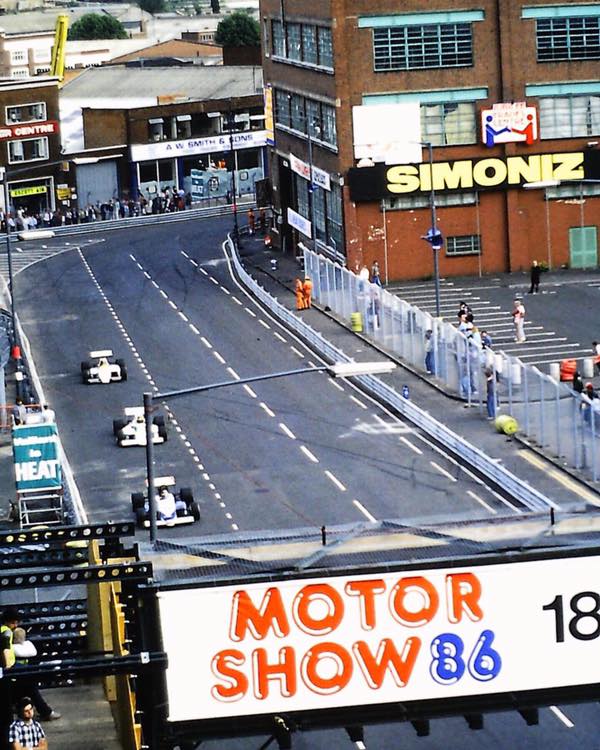

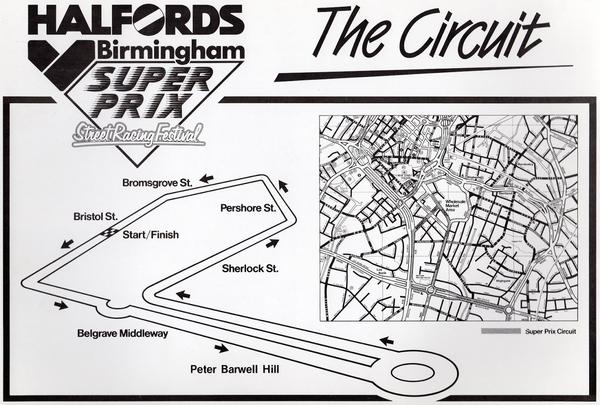

Many had tried, and many had failed, but in 1986, Birmingham City Council and the UK Parliament saw the light and racing finally came to the streets of Birmingham thanks to the Birmingham Road Race Bill. For four gloriously chaotic years until 1990, the Birmingham Superprix was a bank holiday fixture on the FIA Formula 3000 Championship calendar; a bumpy, unforgiving street circuit on public roads in central Birmingham, with a pit area on the forecourt of the Bristol Street Motors Ford Dealership and a main straight consisting of a largely unadulterated section of the A4540 ring road.

Motor Sport Magazine commented archly at the time that ‘the area in which the track was laid out is not an attractive sight’; while it is true that the SuperPrix was hardly the Monaco of the Midlands, the event led to intense racing and many memorable television moments.

While most of the races held at the Superprix were dramatic, a standout is the 1988 edition in which David Hunt’s wayward Lola punched a hole in the brick wall of the Wholesale Market at Loctite Corner, and Russell Spence’s car was hoisted into the air by the marshals’ crane following a spin, prompting complete pandemonium on track below, a racing car traffic jam and eventually a red flag.

Despite the exciting on-track action and the support of luminaries such as Stirling Moss, the costs of hosting the Superprix were prohibitive, prompting Birmingham City Council to put the race meeting out to commercial tender in 1990. While plans for an extended circuit to meet international standards had been drawn up, no offers were forthcoming, and so the Superprix passed into British motorsport history. Only time will tell whether another British city will be brave enough to host a motorsports event on quite the same scale.

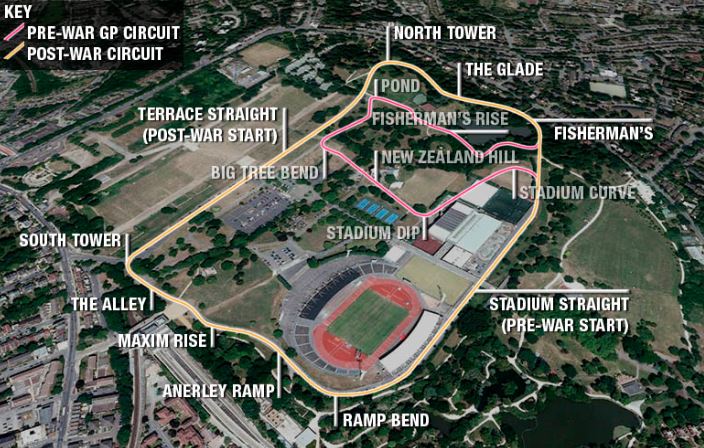

Crystal Palace Circuit

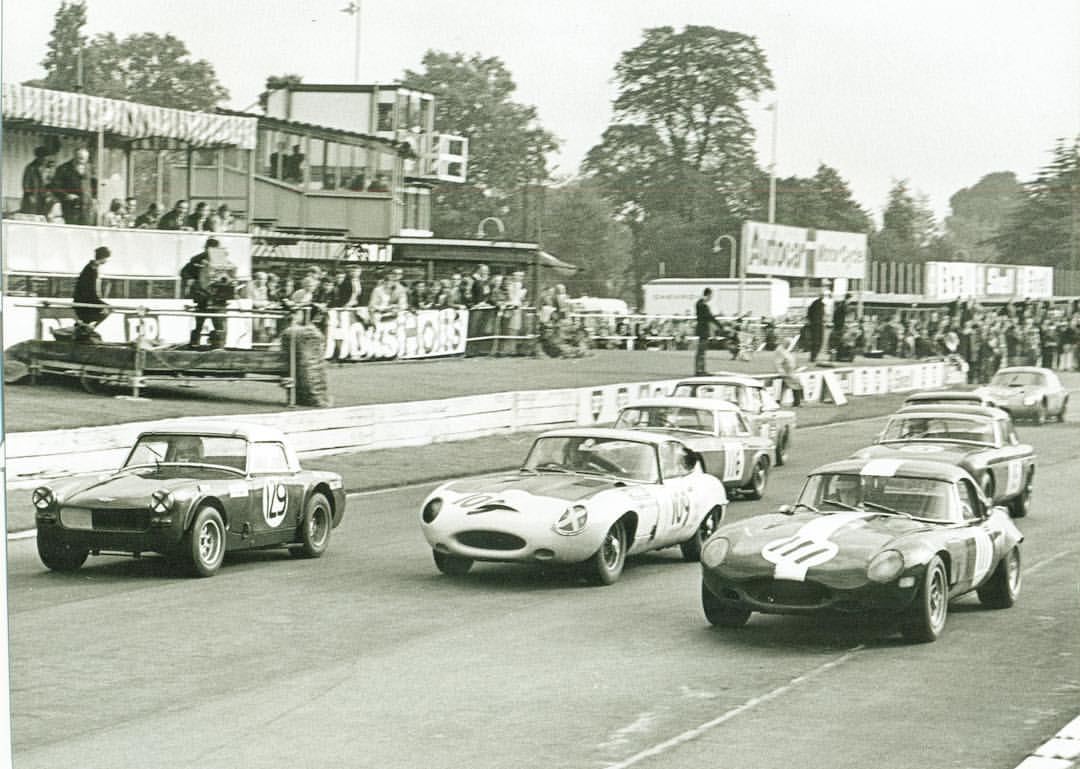

If you look closely at the access roads around Crystal Palace National Sports Centre, and ignore the speed bumps, you realise that they look remarkably suited to spirited driving. Crystal Palace is in fact one of the oldest motorsport venues in the world, with a permanent race track (initially consisting of tarmac bends and hard-packed gravel straights) built on the site in 1927. Originally featuring speedway and motorcycle racing, ‘London’s Donington’ hosted the 1937 London Grand Prix won by Prince Bira in his ERA R2B ‘Romulus’, and later that year, the first televised motor race (the International Imperial Trophy, broadcast by the BBC).

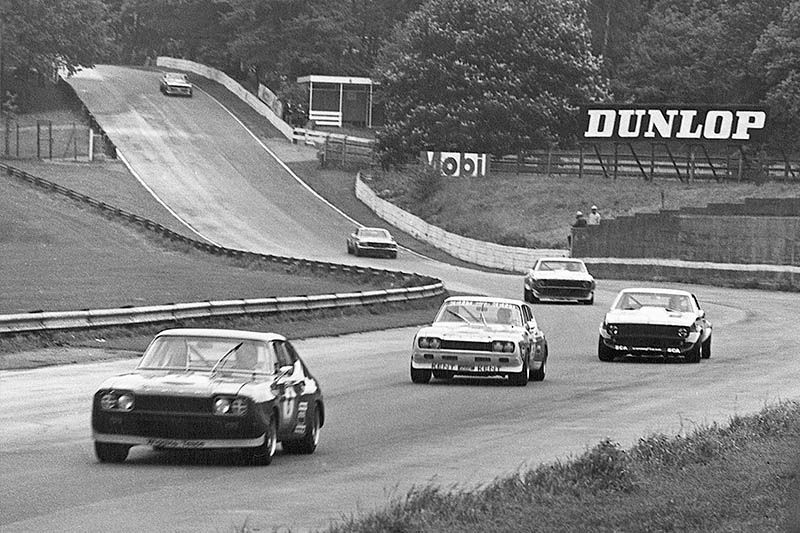

After a period under ownership of the Ministry of Defence during WWII, racing returned to Crystal Palace in 1953, with the 1.39 mile outer perimeter of the GP track seeing all manner of competition including sports and saloon cars, Formula 3, Formula 2 and non-championship Formula 1.

As the cars got faster and louder and the crowds grew, grumbles from local residents increased, resulting in an injunction which limited motor racing to a mere five days per year until the end of the 1960s. Safety also became a concern, with the startling realisation that doing 100mph in a park bounded by Armco and concrete walls was perhaps unwise. After two decades of exciting racing featuring the stars of world motorsport, the track was to shut for good in 1972, with Gerry Marshall winning the final race held in a Lister Jaguar.

These days the Sevenoaks and District Motor Club hold the occasional and wild-looking sprint on the surviving sections of tarmac. Visit what is left of the track and you can just about imagine a time when London was a motorsport capital with Jochen Rindt, Graham Hill, Mike Hawthorne, Jack Brabham and Jim Clark performing feats of death-defying courage a mere cab ride away from the Houses of Parliament.

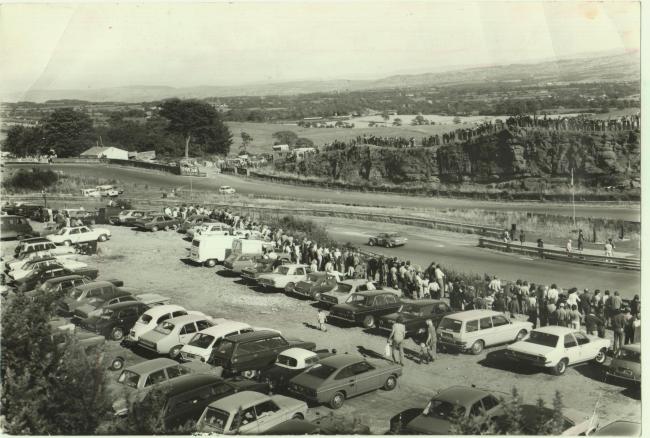

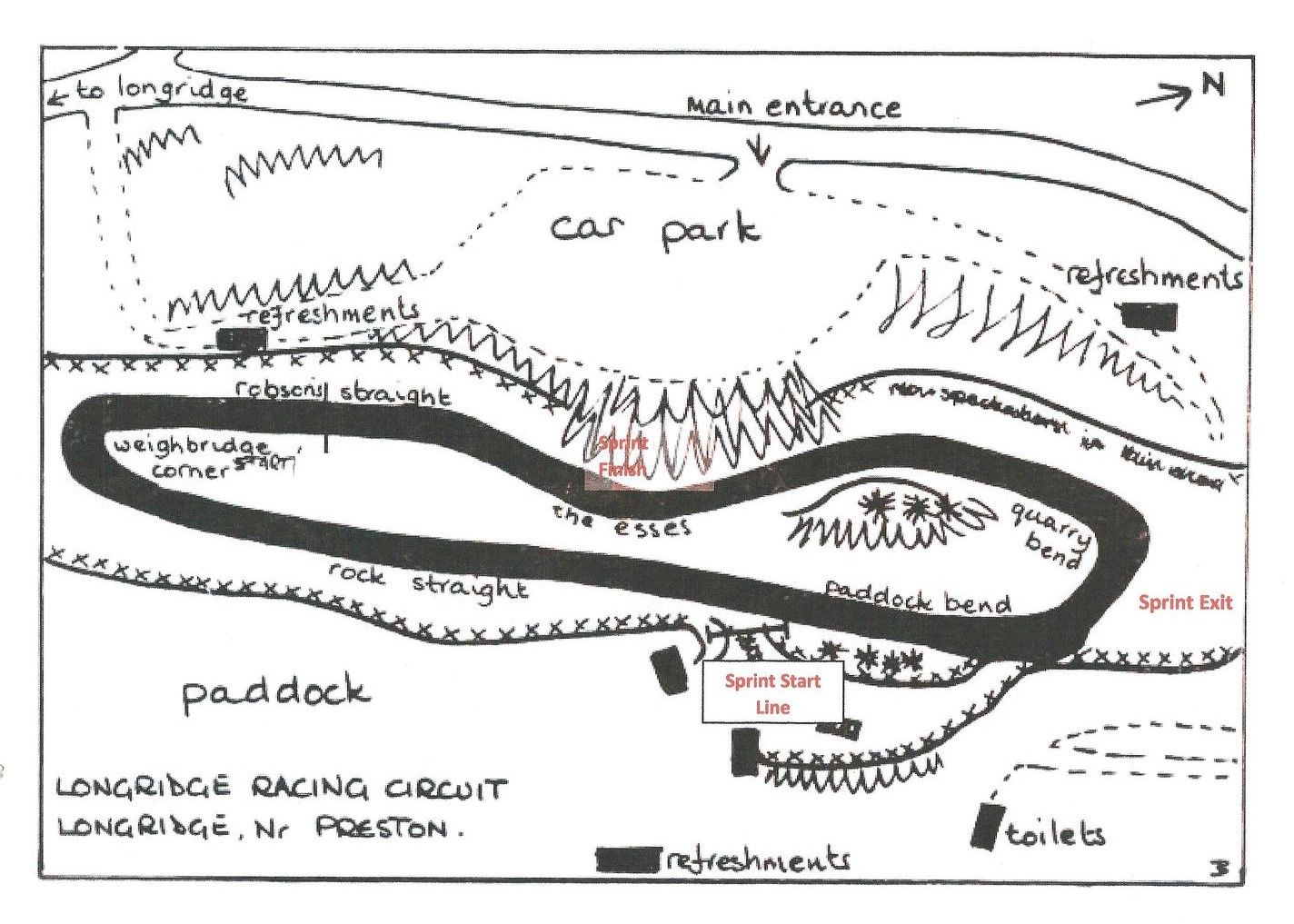

Longridge

If you liked your racing with a Fred Flintstone flavour, Longridge was the place to be. Set in a muddy disused quarry at Tootle Heights on the Lancashire Moors north-east of Preston, and measuring just under half a mile, this diminutive and somewhat bewildering circuit was initially licensed for only ten cars and provided some of the most basic thrills on the UK racing scene. Two roughly similar straights and two hairpins of varying ratio were on offer, along with some dramatic scenery for race photography, a muddy gravel pit lane and crowds climbing up rock walls to get a better view of proceedings.

Official races were held here from 1973 to 1978 (although meets had been held on the site prior to this), featuring mostly two- and four-wheeled club competition with some rallycross thrown in. With a lap record of 23.2 seconds set by Warren Booth’s Scott F2 in August 1977, which suggested an average speed of 67mph, the joke was that if a car spun here, it would probably hit itself on the next lap. Today the site is part of a caravan park, and the quarry echoes with the sound of gentle holidaymaking and the odd BBQ.

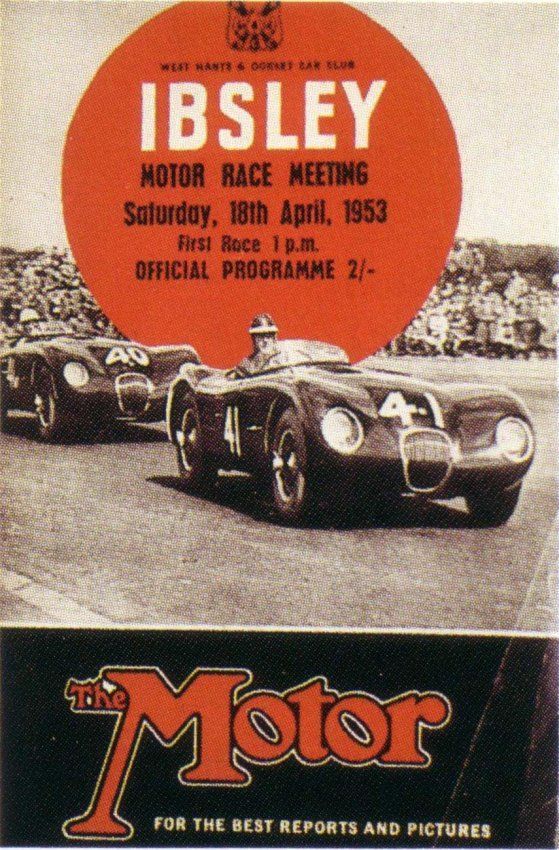

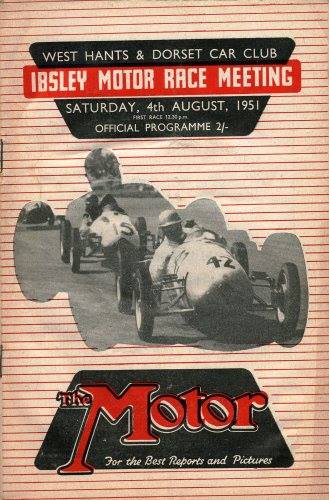

Ibsley Circuit

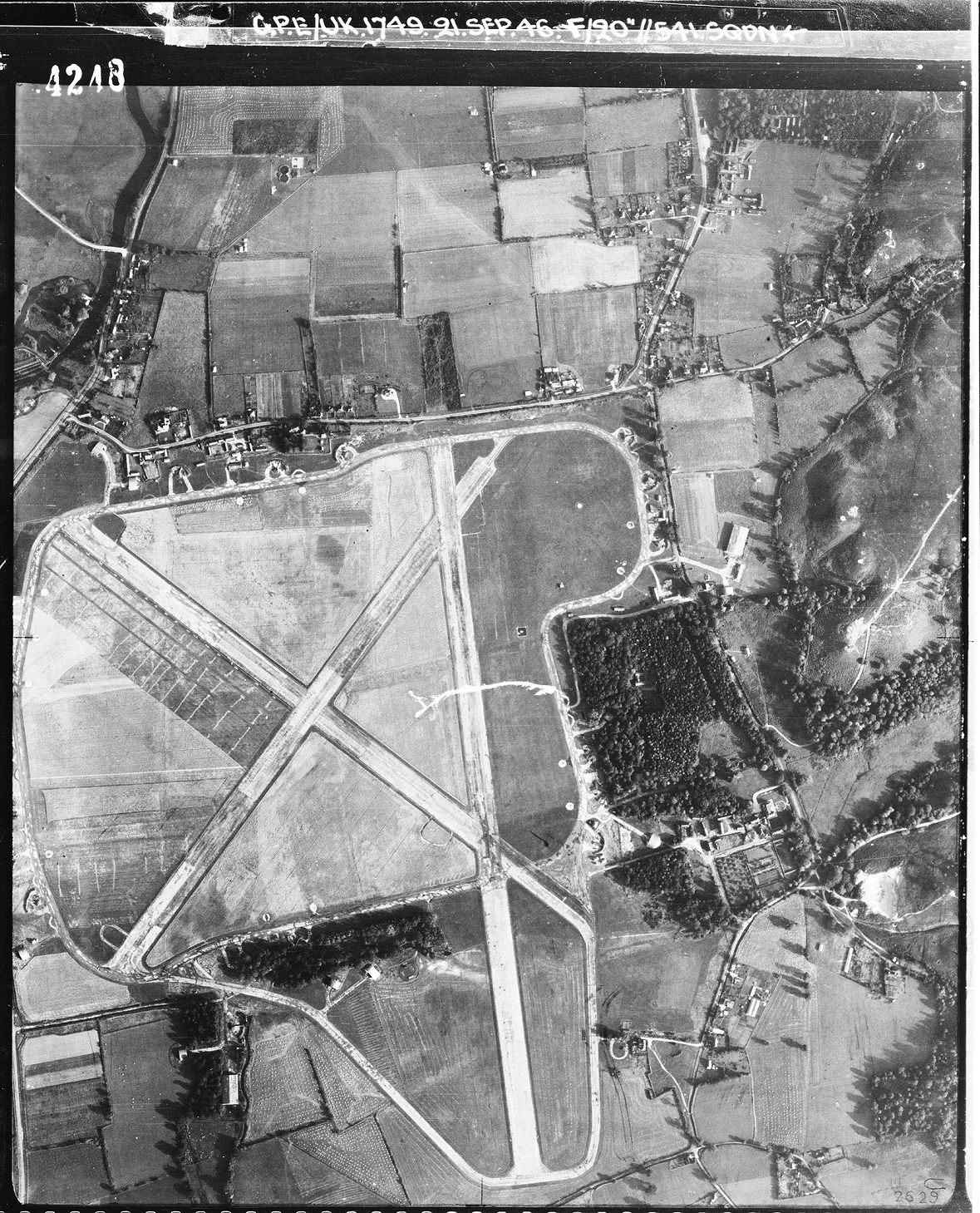

Active from 1951 to 1955 and with races promoted by the Ringwood Motor Cycle and Light Car Club as well as the West Hants and Dorset Car Club, Ibsley Circuit shared a common heritage with many other post-war UK road race circuits in that it began life as an airbase, with the perimeter of RAF Ibsley adapted for motor racing shortly after the war. The circuit saw frequent competition across multiple classes including vintage sports cars, racing cars (including Ecurie Ecosse C-Types in 1954), and the 500cc-plus ‘Formula Libre’ format. Attracting crowds of over 25,000 at its peak, legend has it that Ibsley’s racing occurred only on Saturdays to spare the congregation of the local church from the terrors of racing engines.

John Surtees made his motorcycle debut here in 1952 finishing fourth in a 350cc motorcycle race, the same year that Mike Hawthorn won the Ibsley Grand Prix. A young Colin Chapman also raced at Ibsley, as well as Roy Salvadori, who set the lap record in 1955 in his Maserati 250F.

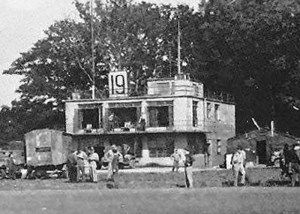

Today the site is completely unrecognisable as either a race circuit or airfield; deep excavation in the early 1960s was followed by deliberate flooding of the quarries, creating the Blashford Lakes. The site is now partly managed as a nature reserve by the Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust and enjoyed by local fishing, sailing and water skiing clubs; all that remains of Ibsley’s past is a dilapidated traffic control tower.

Rockingham Motor Speedway

Completed in 2001 at a cost of £70m, Rockingham Motor Speedway was the first purpose-built oval track built in the UK since Brooklands opened in 1907. Built on a disused British Steel works brown field site in Corby, the circuit was a relatively shallow banked oval which attracted the US CART Champ Car World Series, and offered 13 further track layouts catering for a wide range of auto racing disciplines including BTCC and British Formula 3. American-style stock car racing was also held on Rockingham’s oval from 2001 to 2007, initially named ASCAR and then, bizarrely, ‘Days of Thunder’ after the much-loved 1990 sports drama starring Tom Cruise.

While the site had a faltering start, and felt slightly cold and lifeless due to occasionally empty stands closed for safety reasons, Rockingham was nonetheless praised for a good road racing track layout and testing facilities, and saw a steady stream of motorsport events during its life. The scene of many an engaging racing moment, it was also used frequently for automotive television programmes, and also endeared itself to the motorsport community as the source of entertaining gossip (toxic waste, sinkholes, hidden landfill, and so on).

Unfortunately for Rockingham, after 17 years the circuit’s financial future was unclear. It was sold to new investors in 2018 and motorsport activity ceased after a final ‘super send off’ race event in November 2018 featuring saloon, sports & GT and single-seater races. The site exists now as a rather unromantic logistics hub for automotive companies, a poignant end to the life of a circuit which aspired to be much more than the sum of its parts.