The Apex Interviews 1970 Le Mans Winner Richard Attwood

From the humble beginnings of racing a Standard 10 and Triumph TR3 at Goodwood, to triumph at Le Mans in 1970 driving one of the fastest and most dangerous machines ever created, Richard is one of motorsports’ restrained yet ebullient stars. This week, we had the pleasure of spending an afternoon with him, and we talked all things Grand Prix racing, Le Mans, Jim Clark, the Targa Florio, and much more. We hope you enjoy.

Archie Hill interviews Richard Attwood for The Apex by Custodian. Recorded and produced by Archie Hill. Transcribed by David Marcus.

How did your journey into motorsport actually begin?

Well, it was my father's influence really. We had a fairly big garage set up in Wolverhampton here, and after the war he went to all the major manufacturers in this country, and he asked if they wanted representation in Wolverhampton, and they all said yes. So we got Rolls Royce, Bentley, Jaguar, Daimler, Standard, Triumph, Aston Martin, Rover Land Rover, Vauxhall and Bedford. That's everything except British Leyland or British BMC as it was then. I was steeped in all those cars growing up and being passenger in wonderful stuff from the 50s. Aston's were my favourite I suppose. I've still got an Aston DB2/4, I love that one but it's being done at the moment.

I learned to drive at a very young age on a farm. I always remember I had a careers person came round at the public school I was at, I was about 15 or 16, and they asked, what do you want to do in life? Of course I didn’t have a bloody clue. I suppose lots of people, maybe young kids today, they know what they're going to do from day one. I didn't say I wanted to be a racing driver or anything daft like that. It was obviously a profession I was looking for and I just didn't know of one, and that's what I wanted to do. So that set me thinking a bit I suppose, but really I still didn't know after another year or so, it wasn't clear to me what was going to happen. But when I left public school, I went to do an apprenticeship at Jaguar Cars, which was arranged by my father. My elder brother had gone to Rolls-Royce for an apprenticeship. I think apprenticeships are fantastic.

When I first went to Jaguar, I thought it was a bit like going to school there because you've got a clock-on and you've got to do everything regimented. Of course going from public school where everybody talked quite correctly and nicely and everything else, to the shop floor where every other worker would begin with a letter that you know... I was quite in shock really. What also shocked me was that they'd all got cars because they were earning good money. That was another thing because I thought only really rich people could have cars. It was quite something to actually be able to possess a car and run it. That was another thing that struck me, but then I started my competition in my little Standard 10, there on the Jaguar car park doing driving tests and that sort of thing. I found I was quite good and I won a few things, and that was the start of it really. We are getting around to the circuit racing and for some reason I can never remember, but I wanted to do a race pretty much on my own, and with my little Standard because you have got twin carbs on it so it wasn't a normal car, but it would do about 65, maybe 70, or maybe a bit more if you're going downhill.

And if you've got the wind behind you!

Yes exactly. Why I went and decided to go to Goodwood, which is about the furthest circuit from here, I again have no idea. Before you could compete there you had to go on a proficiency test. I drove all the way down there, of course no motorways, so it took me a long time. It was certainly seven hours, it might have been a bit longer than that to get there, go through all the towns and of course there was no motorway. So quite something to have got there, and of course when I was young I drove like an idiot really, like a lot of young people do, although I shouldn't admit that now. You would think I was worn out but I was really quite looking forward to what I was going to do, although I didn't know what I was going to have to do anyway. I got there and I signed on or whatever you do. I had no idea what I was doing but they said we've got to go out and we're going to just have a look at you driving, going around for about three quarters of an hour and I thought it was quite a lot of concentration there.

I didn't find anything completely daunting, but what did worry me was how to progress or how fast. What they were looking for was speed with safety, no raggedness and a spin, well they would probably say when you've calmed down a bit, have a go again, which I really didn't want to do. At the end of the 45 minutes I came in, and I don't know if I had a race number on the car or not, but they knew who was in whatever car, and how long you'd been out there. They called me in and said that's fine, you can compete. That was the first thing I had ever done and I thought blimey, that's amazing, I had actually passed a test.

Within that same year, 1959 it was, I went down to do a race, it was a members meeting, I don't know what number it was, but it was certainly a members meeting run by the BARC. I have no idea where I finished, I had what I thought was quite good fun mixing it with other people. It was my first experience in competition and I really found it came to me quite normally, naturally I suppose in many ways. That was my first race. To prove it, in Autosport that particular week was a picture of me in my car. I had no idea why, I wasn't anybody. I didn't pay anybody for it. I had been in my first event and it went from there.

My father then provided something a bit more potent and it was a TR3A. My brother also had a TR3A because we were Standard Triumph dealers, so they were probably down as a couple of demonstrations. I went the next year, 1960, I did a whole series of national races in 1960 with the TR. It wasn't modified in any way other than the spokes of the wheels, we put more spokes in, in case they broke. That was it really, that was a Standard TR3A. I went to Mallory Park and that was probably my first real race. This car would do 100 miles an hour, which was a bit different to the old Standard 10, waiting for them to wind up with the gears to change up. I was entered into two races that day, one was a handicap race and the other one was a scratch race. I used to be late in those days, and I was late at Mallory. And you can't get into the circuit without the circuit stopping, then you are let through, by which time I had missed my definitive scratch race practice that had happened. I started at the back of the grid because I hadn't practiced for that particular race, but I was just as a handicap, you set off at different times and you're meant to finish at the finish post at the same time, which never happens. That came first, I had a good race, I won that, but I only just won it apparently because Dr. Tony Goodwin, Chris is his son, Chris Goodwin who does a lot of testing and stuff and he's good at Goodwood as well. His father, I apparently overtook him on the last lap but I never knew that until only within the last half dozen years. But I knew I had won it. And at Mallory you can see quite a lot of the circuit from the paddock area there. You can see the straight and the s'es and everything else. Some of the guys in the scratch race came to look at the car. They said nice car you've got there, and I said well it should be, it's brand new. They said what have you done to it? I said I hadn't done anything to it, it was just a standard road car. I said I've got the extra spokes on the wheels, 60 spoke wheels instead of 48. I said I've also got the 2.2, which was an upgrade, and they no, we've got all that, what else have you got? I said nothing, and I was beginning to get, I'm not really the highest intelligent guy, but I thought it must be, I don't know, but they had seen something that I didn't know about.

Why they had an eye on me, I've no idea, but anyway, scratch race comes up, I start on the back, and I get to probably, it's a 10 lap race, so we get probably a couple of laps from the end, and I've just overtaken I think it was for third place, and I make a classic error - I am looking at the guy behind at the corner, I missed the turn and hoik it in and lose control effectively, and biff the bank on the inside. Egg on face, and that was really the first lesson learned I suppose the hard way. But my father had the foresight maybe to send me with a guy in another car because we couldn't drive that car back. The wing was all bashed into the tire and we couldn't move it. We had to leave it there in the scrutineering bay. I went home with an egg on my face.

My mother never wished me to race, so she was waiting for us when we got back. My friend who I was driving back with, as soon as we got home, he jumped out of the car and he said I'd won, I'd won. I got out the other side and I said no, I crashed, I crashed, which she didn't want to hear at all. That was my first serious race. Then I went through the whole year with the standard car as it was, I never had the time to modify it, but I was really enjoying the racing, I was learning a lot all the time. It's probably the most enjoyable year of racing I've ever had I would say, because nothing was really at stake. There was no money and I didn't have to do it if I didn't want to, although I did. At the end of that year I went to my father and said I want to modify this car so that I can go back and beat all the guys that were beating me. My average finish was about fourth and I wanted to be able to go beyond that. He said we're not going to bother with that, I'm going to get you a Formula Junior. I didn't really know what a Formula Junior was. He was obviously out to see how it went for me, and obviously could see I was really enjoying it. He was my sponsor, without him I wouldn't have done anything at all, I can assure you. I then did three years of Formula Junior and ended up winning that race in '63 at Monte Carlo, which was the biggest race of the year. That put me on the map, and I did all my apprenticeship in those years, and won the most promising driver for that year.

The Grovewood Award, isn't it?

It was the Grovewood Award, yes, and that's the fore runner of what happens today. So it went from there. Just to complete the story, my father said you've done well, you've earned your colours, type of thing, and he said I want you to come and join the business and help me run the business. I had just got a couple of contracts so I was actually turning pro, I didn't probably realise it at this time, but I was. He realised he had let me go too far, which was his own fault, not me. He stepped back and that was the end of that. I said I will join him, which I did. This was '63, so I did it in 71, but by then it was much later than he wanted. Actually it really wouldn't have worked, working with my father, because he couldn't work with his father, and my grandfather started the business in Stafford, and my father had to step away. I think he was probably given a load of money to set up somewhere else, because they couldn't work, they were at logger heads all the time. So he set up in Wolverhampton and they went through Walsall and other areas. We were quite big for the area anyway, that's really the beginning.

Was it the win at Monaco in '63 and then winning the Grovewood Award, was that the moment when you were like oh, I can actually make a career out of this?

Not really, I was just taking every step as it came up, it just happened to go that way. I wasn't thinking I was going to be a professional driver necessarily, but offers did come in and it was a different era to what it is now, completely. There were some drivers who bought drives even then.

Even then?

But they wanted the glamour and the glory of doing it, so they would borrow one of Chapman's Lotuses or something like that. It was just as night follows day type of thing. I didn't make any plans. I wasn't going to say I'm going to be world champion or anything like that. I didn't have any real ambitions, but I just wanted to do well. I've enjoyed it more because I was then self-sufficient in money. Then you realise that you actually can do what you probably want to do, and I wouldn't want to do anything else at that time anyway. There's nothing really in my life in general that I would have changed, I don't have regrets. I do but then I think if I'd got that drive somewhere, I just think it was a very dangerous time, and that's why I did pack it in early in 1971. I was 31 and that was the reason I did stop. There were lots of reasons, I got married and wanted to help my father I thought. Lots of things added up and I thought I'd be quite lucky until that point, so that was it really.

In '63 and '64, the competition in single-seaters with the other drivers was extraordinary. I think in the Formula 2 race you did at the Pau Grand Prix, I think you came second to Jim Clark. From my growing up, obviously I read about him, watched documentaries on him, and I get the impression that he was the driver's driver, and I'm wondering did you see him like that and what were your experiences of him like?

He was just an amazing driver, a bit like Stirling really, who was my idol. I did write to him about my Standard 10 to make it faster, and I did get a reply. I didn't race against Stirling because he had his accident in 1962 and I hadn't really started with international races, Formula 2 particularly, but Formula 2 we did with Jim Clark and all the graded drivers as they called them in 1964. The race at Pau the first year, we were still running the old car because they probably hadn't made the new monocoque yet, so we were always a bit behind. Jim Clark had the latest Chapmans Lotus, and Chapman every year was bang on, brand new car, he was a commercial guy and he was out to sell cars, which of course he did very well, he sold probably more than anybody else, certainly at that time. They were all good, the junior years, the 18, the 20, the 22, the 27, they were the best cars that you could have really. Colin did it really thoroughly and well.

It seems that Monaco as well was a track that you particularly liked, was it '68 that you came second to Graham Hill? Then it was two seconds behind him or something, it was very close.

But he measured that, I didn't realise he was winning the race at the slowest speed, really, because it was a Lotus 49 with the most amazing engine, DFV, and in the BRM I had a V12, sounds wonderful, but it wasn't really, because it was a sports car. The H16 was meant to be the Grand Prix engine, completely failed, and eventually they made that into a four valve engine, but this was a two valve engine. It was a nice car, but until I drove the Lotus 49 the next year, and 69, as soon as I drove it, I hadn't even done a lap and it was just a completely different car. It was completely alive and responsive and just amazing. I realised how far away I would have been if Graham had wanted to, he could have probably, possibly lapped me, he might have done. The realisation didn't come until I drove it the following year. I thought I've done really quite well, but really it was no chance, as has been proved. He has 158 Grand Prix, I don't think any other engine would ever do that, so that was the right engine. But I had experienced it in the F3L in 1968, and I just knew what that was like, because that was a sports car, much more bodywork, but it was still like shit off a shovel type of thing, but in the single seater of course, it was even faster. It was just light years ahead of anything, which has been proved.

Was there good chemistry at that time between the drivers as well, did you all get along very well?

Oh yes. We all stayed in the same hotel, we ate meals together and everything. Jim Clark came to Wolverhampton quite a lot, because he had a girlfriend called Sally Stokes, and they were quite big industrialists in some way. He was going out with Sally in 1962, we had the MRP, we put on a party in '63 and Jim Clark came to that, because he knew Wolverhampton very well, so I knew him on a personal basis. He was just an ordinary guy. He didn't know or have any knowledge of why he was so fast, but he was. He was usually in a gear higher than everybody else as well, so he was taking less out of the car. He was just an amazing guy.

That's extraordinary. Do you think it was just his smooth driving style? That is always attributed to him.

We all tried to do that, I suppose in a way, although obviously not everybody, but that's what I concentrated on as well. I think we all did, you couldn't be too ragged in cars like that because if you crashed, you've got a very good chance of certainly severely injuring yourself or worse. He was just a total natural. It's over the years really, you think of what he did, but the H16 engine which I've mentioned, BRM never won anything like that with those engines. They all broke, but Jim Clark actually, Colin put one of those H16s in the back of a Lotus, and Jim won the American Grand Prix with that engine. He did, but nobody else did. It just shows there were many things like that, a feel, a touch, a sensation. He was running out of oil in some races, so he'd coast through the corners and then get the engine going. Nobody told him what to do.

It's like an artist behind the wheel.

Yes, artist is exactly the right word. In Formula 2, when we got to Formula 2, we've got lots of really quick drivers now, and the idea was to combine that formula with the young drivers, the junior drivers come in and then compare themselves competing with the much more experienced drivers. which was a good idea. In 1965 when I was in a three-year-old Lotus 25, which was probably a mistake, but anyway, I was in Formula 1 and Formula 2, and we were just together, all of us, all together all the time, there was no differentiation. People didn't have their own helicopters and flew off everywhere. Jim did have a plane. Jack Brabham I think was probably the first one to have a plane, I'm not sure, and Graham got a plane, and they all started getting planes, but helicopters weren't that good then I think. He was the man of the moment, definitely.

Looking back on the single seaters, did you enjoy racing them?

Yes I did. I think you are more one with the car, in the middle and you see the wheels go round. It is the ultimate, isn't it, and Formula 1 certainly was then, and it is now seemingly still the ultimate that everybody looks up to Formula One as, it's got the name, isn't it, if nothing else. In a way sports car drivers, I think those drivers drive harder than Grand Prix drivers. You see the qualifying times for Formula 1, then they start racing and they're not doing anything like that time. I am a purist I suppose, I shouldn't really talk about that.

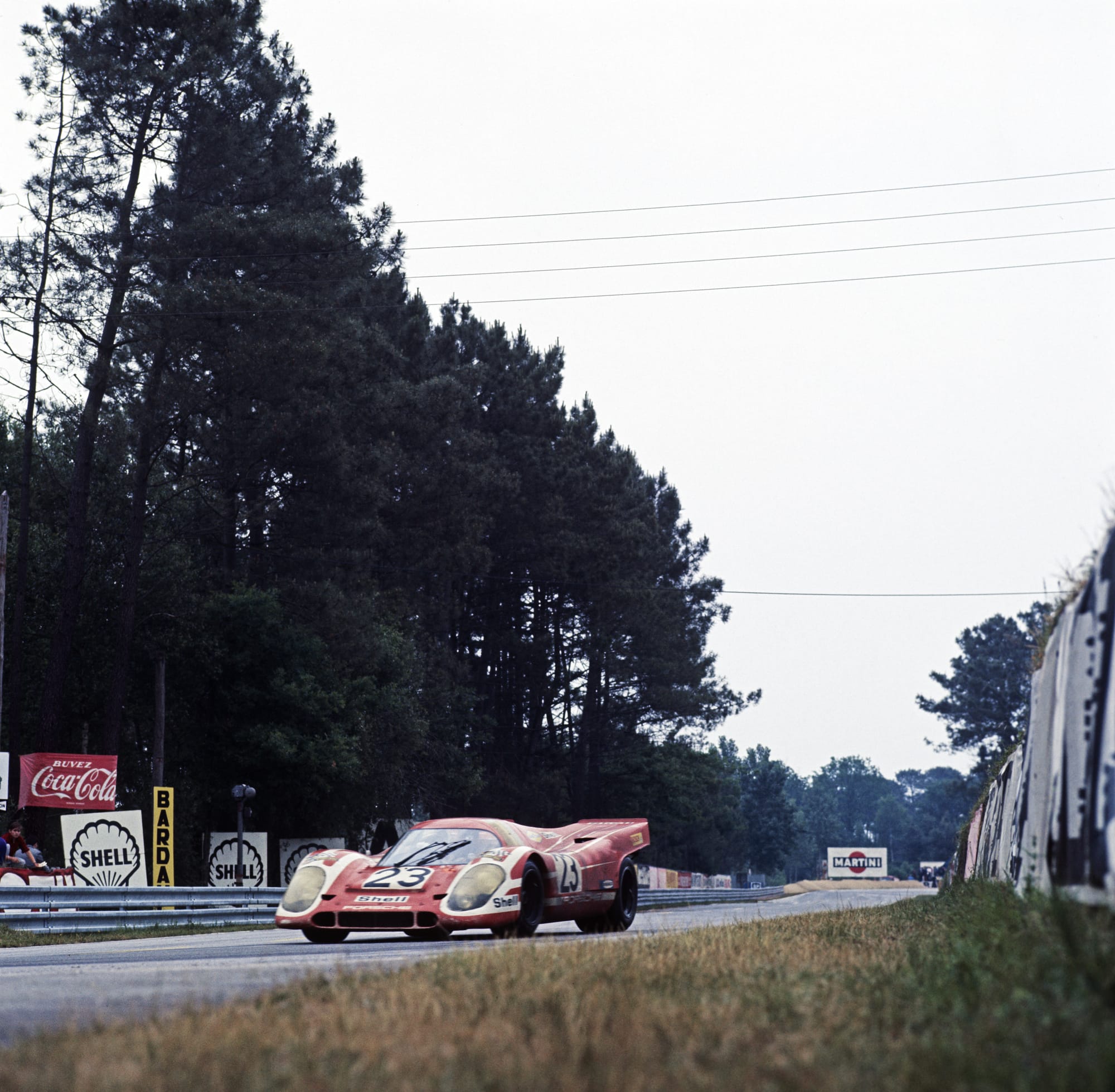

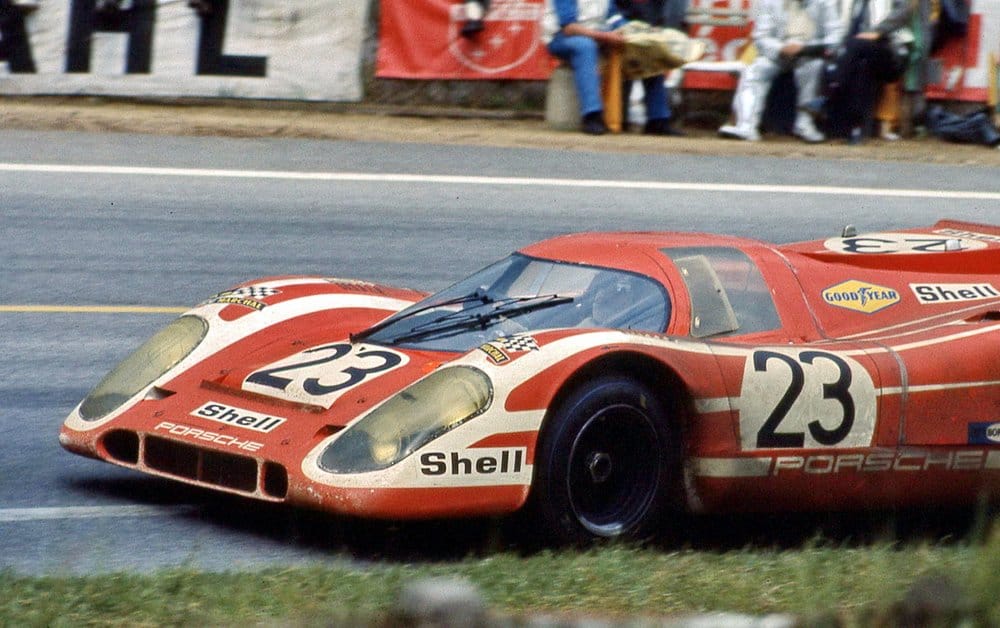

On the sports car side, the race that is often attributed to you is obviously your win at Le Mans in 1970 with Hans Hermann in the 917. From my understanding, that wasn't a race that you particularly expected to win, is that fair to say?

Absolutely.

It was under terrible conditions.

It was that, but it wasn't that. Before the race started, I said to my wife said, we have no chance in this race. It actually begins the year before, 1969, because I drove the long tail, the first car, the first 917, which was totally unstable at any speeds approaching 200, probably around 180. You could feel the car was off the ground, and every mile an hour makes a difference. The car was capable of doing 235, and I don't think any car had been anywhere near that speed before. I don't know what the 7.0 litre Fords did, but they were built a bit like a brick and I don't believe they'd have a horrendously high top speed, but 235, we were chunking tires as well, they were standard Dunlop race tires, but big ones, so we had to back off a little bit, which actually only knocked about 10 MPH off it, which wasn't much and it didn't really make much difference. To give you an example of the stability, there's a kink at the end of the Mulsanne straight, and any car I have driven, ever, except 1969, it was flat. It was an easy flat, it was just steer it through flat, and this car you could not, you had to back off. You had to brake, you had to set the car up with a bit of a lean on it. It was a nightmare to drive, which is why I didn't want a long tail in 1970. That's what I'm coming to. The gearbox actually ultimately broke on that car in 1969.

For some reason, the factory rang me in February, and they said we would like you to drive one of our cars, they said we'd like to ask you what configuration of car you want, which I thought was amazing. Really I think in 1969 what they thought, I was completely, we've got three hours to go. and we were six laps in the lead, now why didn't somebody tell us that you could start pocketing it down a bit, but we had no orders like that at all. I don't understand that, I still can't understand why. Then when the gearbox broke, after the first stint, the sixth time, Vic Elford did the first start, so he did a double stint, then I did a double stint, and I wasn't used to the amount of power this car had got, the speed of it. It had got maybe nearly 600 HP, but after my double stint, I'm already resting my helmet on the rear bulkhead because my neck was going, and on that early car, there was two exhausts out the side under the doors of the car and the other two out the back. They changed that later on. The noise, I'd got a blinding headache, and I thought after two hours, it was about 50 minutes per session I think, I thought I don't know if I'm going to be able to get through this, but you do. I went through a lot of pain in that race, a lot of pain, and when it broke, I was totally wasted, but I was totally completely relieved that I still had my life. I was completely finished. I think they saw that as disappointment, but it actually wasn't at all. I could not have given a monkey's about that race. I do mean that, and I hadn't won it. I hadn't won it.

So we come to 1970 now, and I've ordered a short tail, smaller engine, because I don't want to break the gearbox. One other thing I said I want Hans Hermann to drive with me. They said okay, so that was set in stone, that was in February. So by June we had done a few races and now the new 5.0 litre engine was a stonker. I had loads more torque and everything else, and it was much easier to drive. It sounds daft but it was. We do the qualifying and I think we're 15th on the grid, and I'm thinking oh my God, I've done a really stupid thing. Because in my own mind, I'm thinking if 14 other cars are faster than us, some of them were also 4.5 litre engines, but they were driving them faster, but Le Mans wasn't a race where you drive fast, because if you drove too fast, then you're going to break the car, which probably happened in 1969. I said to my wife we have no chance, we've got to wait for 14 cars, all good drivers, and they were, you look at the grid and you think bloody hell, but they all suffered some sort of malaise, some of them were driver errors. The conditions did get difficult, but actually by the time of the major rain, I think all the frontrunners were gone. After 10 hours I came in and they said you're in the lead. I just couldn't understand that at all. But of course, you don't see all the retirements and you're not always out there anyway, you're having your breaks so you don't see the other retirements. It was just insane, so then the most difficult part I think, is you're then defending a lead for now, more than half of the race. You've only done 10 hours, you've got another 14 hours, and the conditions got really seriously bad, where you think gosh, I might as well come in because we're just not making a lot of progress here. That was the most difficult part of the race. The concentration levels, at any moment the car could let go, because of aquaplaning and god knows what.

You have to drive according to the conditions. People ask me sometimes, what's it like driving down the Mulsanne Straight at 200 plus miles an hour? I said in the rain like we had, you don't drive at 200 miles an hour. Apparently there were three Ferraris that went off in one accident, because one of the drivers going through, I learned more and more about stories reading back, but coming out of Whitehouse which I thought was the most fantastic corner, just before the pits, and one of the Ferraris had got muck on his screen and he'd put the wipers on and then he couldn't see anything. So two other Ferraris were coming out when they just piled into each other. That was three out in one accident. Lots of things like that happened. The difficulty was the second part of the race, not the early bit. We couldn't do anything about it. The reason why we were so slow, because in 1969 we had a five-speed box, and in 1970 we had a four-speed box, and we weren't allowed to use first gear because we wanted to protect the gearbox. I guess they had strengthened the gearbox, but I don't really know that was a fact or not, I don't know. But anyway, the problem we had was we had to use second at Mulsanne and Arnash Corners. The torque of the 5.0 litres would just walk away from us there. If they had got four-speed boxes, which I presume they had, and the long tail cars were 30 miles an hour faster. We couldn't possibly drive any differently. A lot of people think we sat back and we just waited for others to fall apart, no, we were driving sensibly and quickly but not risking anything, and we ended up winning it. It was a crazy race. I think the fewest finishers on record, it was just mad, the whole thing was mad.

You won the race, and I suppose at that point you were just glad it was over?

I had mumps which I didn't know about, which got me here, not down there, and I couldn't eat anything at all through the race, anything with any taste went straight to the glands. It was horrible, I didn't really know what was wrong with me, didn't find out until I got back home. Went to see the doctor here on the Tuesday, I didn't know. Because we didn't have medics, we didn't have anybody in massage or telling us what to eat, you just had to do it yourself, manage yourself, that was it. Whereas today it's completely different. It's obvious what to do now, but for me, I don't know what they could have done for me anyway. So I was again wiped out at the end of the race. They at short notice in 1970, they wanted to have a victory celebration dinner, I don't know where it was, anyway we had to get there, so we got there, Veronica and I, and after about 20 minutes, I just could not stay awake, and we left, so that's how I felt. There was no big celebration. They did a celebration on the back of a truck, there's a picture of me and the champagne over there, there was probably still a bit adrenaline running through my veins at that time, but that evening we had to go. I was worn out, I didn't know what was wrong with me, I thought it was just I'm a wimp, but it wasn't that I was a wimp at all.

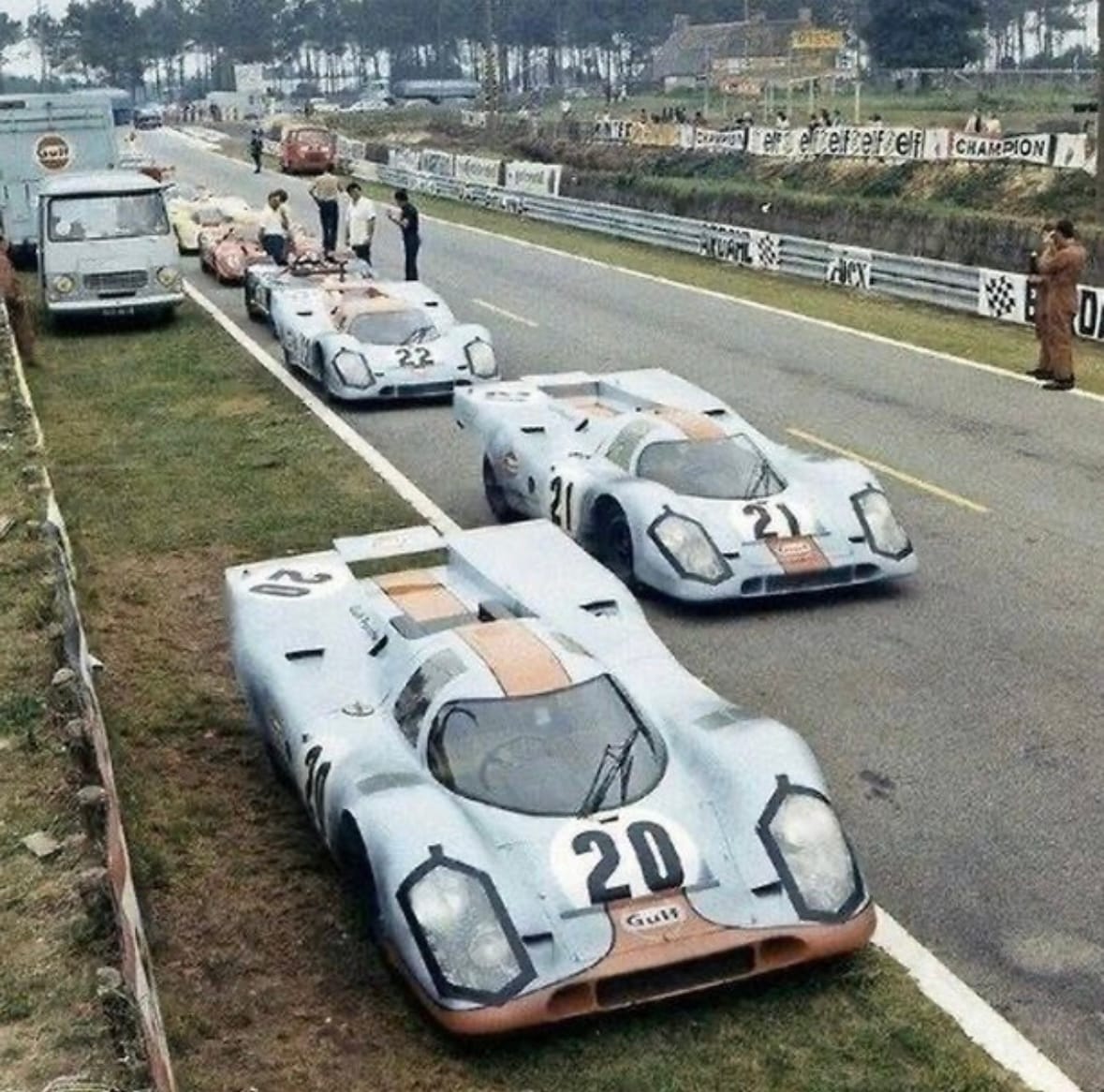

Then in 1971 I drove the third car for John Wyer, and John and I got on very well, and when he wanted a spare driver, he used to ring me up. I was driving with a guy called Herbert Muller, and Herbie Muller was a crew cut Swiss and he was a wild child really. We did the filming at Le Mans, straight after the 1970 win, the Solar Village was inside the circuit, and they had built a route to it to get to it from the normal road, and there was a hairpin bend where you had to go quite slowly otherwise. Anyway, Herbert Muller during the filming he always racing, a lot of racing I was racing around, I never raced anyway, I was just so slow on the road, I really am. I'm not fast at all, and I just set off early and I get there when I get there and everything's wonderful. But he had quite a big off on this hairpin turn, which doesn't surprise me at all. The American crew, they named that corner the Muller Chicane, which I thought was fantastic. I knew what I got, but I was driving with Herbie Muller, so I gave Herbie a big pep talk over dinner and before the race. Actually in the race he drove exactly perfectly, he really did. We were doing well and it was between our car, the Gulf car and the Martini car. We were in car number 19, which is a car I raced in the classic Le Mans. Anyway, we had a gearbox problem in the middle of the night in our car. It took about 45 minutes to change it too, because you couldn't just change the gearbox, you had to change the internals. Some years you could change the whole gearbox. Audi in the later years used to have the whole of the back end of a car. If they had a gearbox problem, they just took the back half of the car, pulled another one on and carried on, so it does depend on the regulations, what you're allowed or not to do. Then the winning car came in and they had exactly the same problem, only about an hour later, something like that, and they now knew exactly what to do. They got buckets of water ready to chuck all the gears, and they did it in about 20, 25 minutes, and we lost the race by only 5 minutes. So as I say, the one race I knew we weren't going to win was 1970, because we just weren't fast enough.

You drove, like you said, the early iterations of the 917 in 1969, so you were familiar with the development process of these racing cars, and I believe you were involved in the development process of the GT40?

Not much.

Did you ever meet Ken Miles?

No, he was a Brummie and he was not far from me, but I think he must have gone to America in the early 60s I would say, but I don't know that. The 7.0 litre cars came on, did he drive before in the other American GT40s? I don't know, before the 7.0 litre came in 1966, they won in 1966 and 1967 with the 7.0 litre cars, but whether he was over before that, but I never met him, no. I think he would have been in America before that period, to do the work he was doing because there was a lot of development. I would say got to maybe in America from England, probably in 1963 or 1964, I would guess.

What was your involvement, because you did drive some of the early iterations of that car, didn't you?

I did but I didn't do a lot of the development. This is 1964 now, and it was a development from the Lola GT car. Eric Broadley - brilliant designer, I don't know if you ever saw one of those Lola's, I don't know what Mk it is. Anyway, his Lola GT was, I have driven one at the Festival of Speed, it must be nearly 20 years ago, maybe it was 20 years ago, and it was so small, it was unbelievable, and a pretty car too, it was a very advanced car. I don't know how similar the GT40 was to that, I mean the GT40 had a big steel tub and I don't think the Lola was made like that, but I don't know, but we didn't test the Lola GT40 before we got to Le Mans because it wasn't ready. It wasn't ready until the day of the race and it shouldn't have been entered in the race because it was late for scrutineering. There were lots of dramas about that but that's another story.

The GT40 I drove, I once went testing at what's the name of the new test site there, Mira, I don't think we did any running on the banking circuit, it was a very initial test, and it was probably just before the test day, they used to do the test days three weeks, in April I think it was test days, and it's part of this I think, I didn't go on the test day with the car, but they wanted to make sure it was all right to do that test day. We met at about 10 or something like that and we were all finished by lunchtime so we didn't do much. Basically all I got to do was do a couple of full on starts to make sure the rubber doughnut things, the half shafts were connected to make sure they were firm, big enough to take the torque of what we were doing. Although we wouldn't be doing that at Le Mans but it was just to test it out, and that was fine. The other thing was to bed small brakes in for the day that we've got to come up to, and the brake pads had to be burned in, you had to keep your foot on the brakes while you press the accelerator on, you had to burn them until they, and they were DS11 pads, which was the only way you could run them in. They weren't quite bedded in correctly and John said, Attwood you are not brutal enough. But I think we got it right in the end. I didn't do much, because they had a lot of front line drivers in the team and they were using them with lots of experience. Bruce McLaren would have been one, Phil Hill would be another one. I don't think Richie Ginther did much, but they had some better drivers if you like who had more experience than I had.

I don't know why I was included in the team but it might have been my connection with Lola and Eric and the fact it's a bit of a carry over from the Lola GT, I don't know, but anyway I got a drive in that one. I think I got a contract with Ford of America as well, because I drove a Shelby Cobra at the Nürburgring, only once, and it was the most awful car, because the track was awful, that's why, and it was all down to the track. The track was very cambered in the middle of the road, so if you want to overtake someone, you've got to take some risks to go by someone. I remember I took off maybe 30 times a lap in that car, it was like a bucking bronco, it was terrible, yeah. But I've driven a Cobra in modern times, and the car is fantastic now because the surface is fantastic. You've got Armco all the way around, you can hardly kill yourself now. Whereas if anybody went off in that track in the old days, you would more than likely die because you would hit something. People call it the green hell, but to me it's not the green hell, they don't know what the green hell was. The Green Hell was when it was built in 1927, and it's been resurfaced many times since then.

Did you meet Carroll Shelby?

I did. Only once really. I had met him on one or two occasions, but I got to know him, well the first time I met him was at the Nürburgring. He had got three cars there and they were all the silver blue colour, which obviously denoted the 1964 colours, because the year before, or one of the years before they were black. Anyway, they were proper Shelby jobs, there were three there. Jochen Neerpasch was there, I think he was one of the drivers as well, but I was driving with Jo Schlesser. There were two quite long qualifying sessions before the 1,000 kilometre race, and on the first qualifying, practice, I call it practice, one of the cars was destroyed, Shelby cars, finished, they couldn't do anything with it, it was mangled. I can't remember who it was. I thought they died, but they didn't die, until some years after, I thought somebody had died. Then the next qualifying before the race, another car was biffed, but they had to do a lot of work on it to get into the race.

Before the race, Caroll Shelby said, he would take three cars, you only have one good one left really, and he said, please just finish the race, he didn't want any more crashes. I felt very sorry for him. Anyway, Jo and I had driven before and we got on really well. He was a French guy, fantastic character. We both drove it as we thought we should, and we were both similar, and we won the class, and that's all Caroll really wanted. So he probably went away quite happy in the end, although it cost him quite a bit of money. We were driving back, we had been at the garage and I was driving back with Caroll Shelby driving me, and I knew the road going down there because I'd been there, I think previously I'd been staying also down in this place, and I realised that he got his head so full of stuff, and I knew there was a hairpin bend coming up, and I didn't think he was really realising where he was. I said 'Ah', and as I said that, I don't know if he had fallen asleep, he might have done, I don't know, and he put the brakes on because he obviously realised that he should be doing something because I had said something, and he managed to get it all going together. He apologised profusely, but if I hadn't said anything we would have gone flying off, we would.

After everything, to go out like that, goodness me.

Yes, we would have arrived at our hotel a bit quicker than we thought!

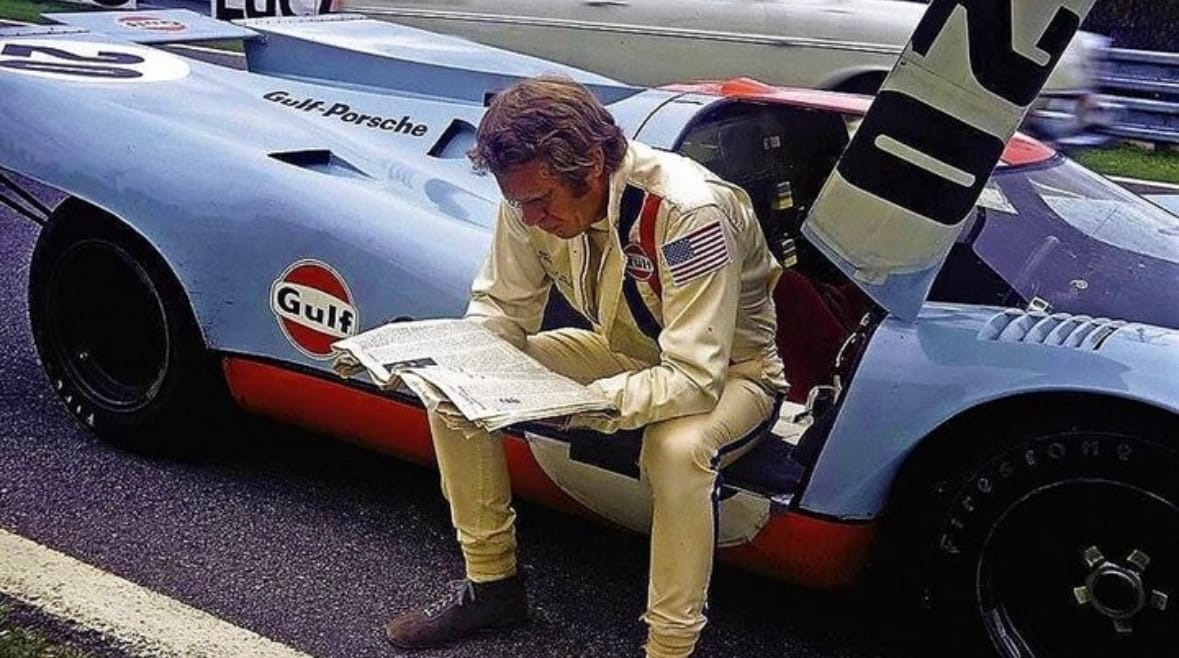

I'm jumping around a little bit but I want to talk about, obviously you said after you won Le Mans in 1970, that's when you also filmed Le Mans. I've got my copy here. If I could transport anywhere in time, to go back to the set of that film would be heaven for me. I would love to hear about what a day in the life on the set of that film was like, because in my head, I just imagine you're there with all your friends, all the racers are there, you're shooting a film with Steve McQueen, I don't know if it gets much better than that?

I know, you are absolutely right, but there were many days when we didn't do anything, because the light wasn't right, or I don't know what it was. I still think today, I think some directors, they're all empowered to desire all sorts of things. Many days we didn't run, but that was costing a lot of money to do that. The film overran, on time and on budget, I think the budget was a million dollars, which in those days must have been a fortune. It went to seven times that, it really was a disaster. Somebody brought it to my attention that at the beginning of the film, Steve is driving around the 911 and it's very scenic and wonderful, actually it's quite a cult thing now, and of course the 911 has become so huge over time and the fame of it and everything else, but there's not a word spoken for the first 43 minutes or something like that. You find that's amazing in a film, can you think of another film where that could happen? Are there?

2001 Space Odyssey I think is a very long opening, but that's sci-fi, for a film like that it is bizarre.

I can understand it because one of the famous directors, John Sturges, he came on board to start with, then him and Steve obviously had a falling out, then they had another one or two after that, then the script writer was in a similar vein, and it actually, I could see why it didn't, the action shots were fantastic and they were real, and I was in most of them. The action shots were really, he wanted it done at full pace, he didn't want the film speeding up or anything like that. We were really hanging it out there. There was one shot where they wanted to pan the one car coming past the other car. This car overtaking would hit a spring-loaded boom at a certain speed, otherwise if we went too fast, we wouldn't be able to drag it around. It was hanging out the back of my car. The pan came absolutely correctly right spot on first time thank god, we're given a bit of extra money that day, danger money, but that was as much involvement and that was good, but there were a lot of dead days where they can't make their minds up on what they're going to do next or the weather's not right. The weather is much less predictable now than it was then. We were staying in chateaus and it sounds very grand and it was, but in the end you want to try and get the job done. Veronica would tell you that too, many days she came for a few weeks out there, and she didn't need to be there, she didn't want to be there. We didn't suffer anything, we were well looked after. Looking back, I suppose when you look back on a lot of things, it actually was not that bad, but it seemed it was at the time. He was intent on getting it right and he did a lot of things that were quite dangerous, but he was lying down in the middle of the road with us zooming past him and everything else. He just was a perfectionist, he wanted it so right.

You obviously spent a bit of time with him as well.

Yes, we had dinner with him two or three times. He was just again, an ordinary guy, and he really wanted to do what we did, and I suppose we wanted to be what he was, but there's only one Steve McQueen. There are loads of us, but he was in awe of us as well. He was quite a driver, he finished second at Sebring with Peter Revson in 1969 I think it was.

One of the other races I wanted to ask you about was the Targa Florio. Again you hear stories of that race, you see these old photos of it and everything, and to me it has a certain allure about it. Do you have fond memories of the Targa Florio, how did you get on with that race?

The first time we were going to do the Targa Florio for Porsche was in 1969. They had chosen drivers from the year before with some trials and races. I was tested, it was all through Huschke von Hanstein, and he was always good at spotting talent and drivers looking for Porsche, probably Mercedes as well, I'm not sure. So in 1968 I drove, I think it was a 907, at Watkins Glen, six-hour race, and I was driving with Tetsu Ikuzawa. I can't understand why he didn't drive for the factory thereafter, but he didn't. I didn't know why. I don't think he did anything particularly wrong, but maybe it was his choice not to do that and do something else, I don't know, I never found out. I met his daughter at Goodwood.

Yes, she was at the Revival, wasn't she?

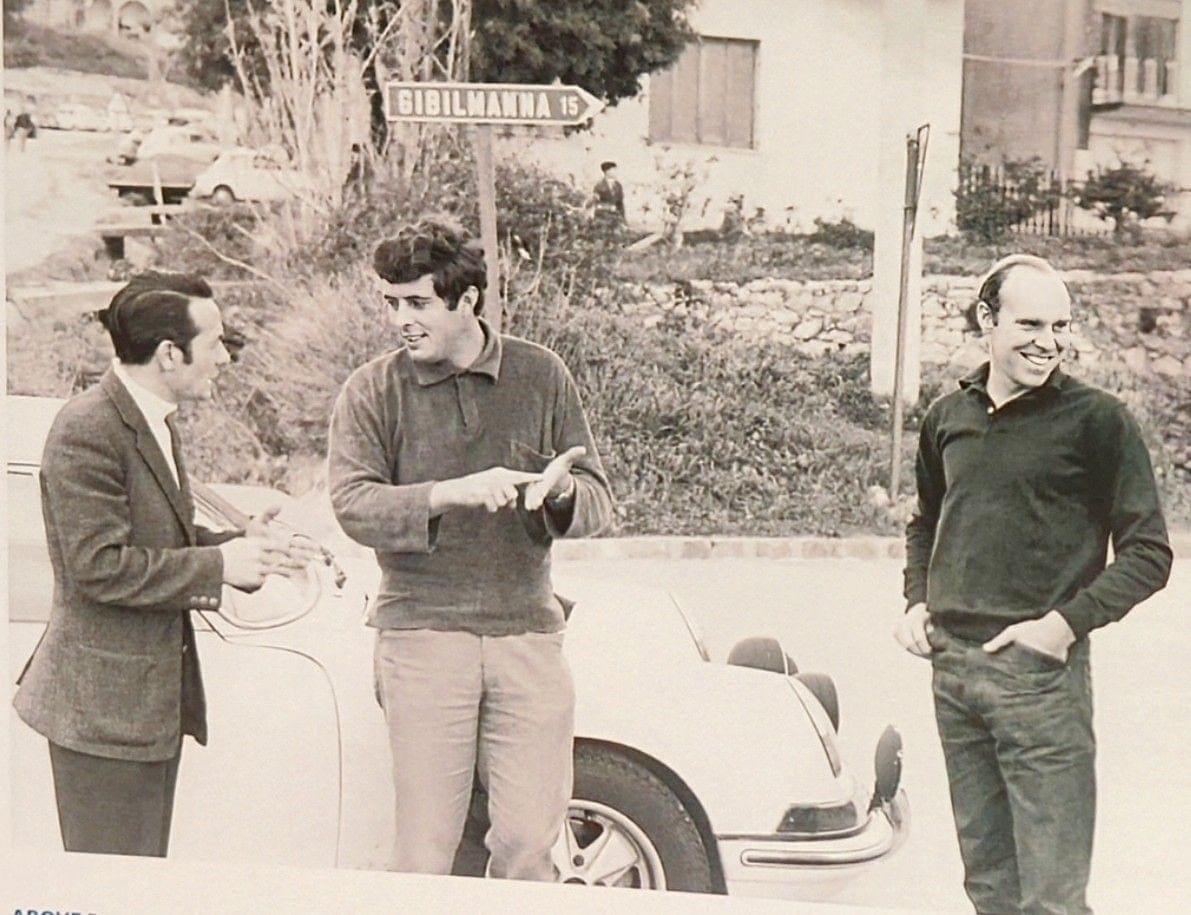

Yes, last year I met her there, but I never, I don't know, it wasn't long enough to ask for it. But he didn't come over. But anyway, it was always a mystery to me why he didn't join the club. But the Targa Florio, we had a meeting at Stuttgart before the year started. I hadn't done the Targa but knew it was a long track. I thought the Nürburgring was bad enough, but then the Targa would be something else. The only question I asked was, I've actually never been to the Targa, and maybe you've got the drivers who've been there, so maybe we'll get somebody to do the Targa in place of me, and they said Attwood, you will learn the Targa Florio. I thought okay, I've got the order then haven't I? Before we start the Targa itself, Brian Redman had never been to the Targa either, so in February, we drove a couple of 911 Rs down there. We got 10 days, it was a day to get there and a day to get back, so that's 8 days. Anyway we drove down all through Italy and everywhere, then we got the ferry, we got to the other side, Palermo, and we then have to find the track.

Before we set off, I said are we going to take any spares with us for the cars? They answered why? Well because I am used to British cars. No, the cars will be no problem. Anyway, they did, they put a set of brake pads in, which we didn't need, and a top up of oil, a small can which I've still got actually at home, and we didn't need that either. Because the dry sumps on the 911's are quite big, so we didn't need the oil either. So they were quite right, we didn't need the spare parts. But we were going down, I think we were pretty much wanting to get there as soon as we could, so we were going as fast as we could, but the cars were short geared, because the 911Rs were short geared for the hill climbing. So we could only do about 105 miles an hour, and the engines were screaming their nuts off, and we couldn't go any faster than that. I am sure loads of cars were going by us, and they probably thought, why don't those bloody prats change to another gear? But that's the nature of the car, which was frustrating in a way. But on certain atmospheric conditions, the inlets would start frosting up and then they started misfiring. We thought shit, we don't know what's wrong with these, I told you something had to go wrong on the way down there. So we stopped at one of the rest places and we lifted the bonnet, and you could see much more of the engine then, and all this frozen stuff was around the carburettors. Was it injection? I don't know, it must have been injection, do you think, 1960? I think it would be injection I'm sure.

Anyway, so we could see the inlet system was all frosted up, so of course we let the engine just heat it all down to water and off we go again. But we thought we had a problem, but we hadn't got a problem, but it just delayed us a bit more. But when we got into Sicily, we got no maps or anything of where the track was or where our hotel was, but they said you'll find it from Palermo, you follow the way to probably Cefalu or something like that. We happened to, one of us spotted a tiny sign saying, Targa Florio, with an arrow just up to the right. So we both stopped and went up there, and we got to start finish area, so we knew that was it. Then we thought, what are we going to do? We've got eight days, so first day we'll just drive around and see how we're getting on. I think we followed each other around for the first lap, we did each in our cars, because if you're passenger you don't really look, but if you're driving you are probably more likely to take things in a bit more. So we drove around following each other around, but every now and again we get to a road we didn't know, so we had to wait for a farmer to come along and say Targa Florio, which way do we go? We had to do that two or three times, and after about, well it must have been at least a couple of hours I think, we get back to the start finish line, and we both opened the doors and we would just collapse on the floor with total laughter, there's absolutely no way we are going to learn that!

It was a real uphill struggle to believe we could do that. I think the first day we drove round, I think we did three laps after that, and we got back to the hotel and we had a debrief to ourselves, and we were both really just driving around fairly aimlessly because you can't remember landmarks. We then decided we would have to learn it in sections, and we decided we were going to do it in two mile sections. Then we were on about the third or fourth lot of two miles, then we realised we were never going to get through the whole circuit before we've got to come back. So in the end, we learned it in thirds. So we did it that way. I think Brian, because he's done rallying, I still think Brian has said that he doesn't, I think he said he didn't know it, but I thought hand on heart I did know it. So this was in February and then we go before the race starts in, was it May, probably May, and I get there and so I go around in a 914 I think, because they had taken one of those up because they wanted to test it out as well, so just do another lap or two of that, and it seemed okay to me. I had then given them the 908, but one that's not going to race, and it was much faster, a lot faster. There was one section where there's a, it's soon after the start, but after about four or five miles, and it's a series of left, right, another left, right, and then a left and a right that goes onto the straight. The third one you come out obviously with some good speed on. Well I learned on my first lap that I came up to this bit that I've just described, and I mistook the second left for the final right. How I avoided what I've got myself into, I really, but it was a real heart-stopping moment. It was so close to be smashing the car to pieces, probably myself as well. But what would happen was, and it's something that probably somebody could quantify nowadays, but my brain had learned the track at a certain speed, and my brain couldn't keep up with the pace of this car now, because it was going so much faster. It was all whirlwind stuff, and that's when I really did build myself gradually up with speed, and we had the time to do that so it was okay. But I never know really what happened.

Time wise it was all so chaotic. I have no idea how well I was doing. There was a halfway point, but I don't think there were any signals, there was nothing to tell us what we'd done, so it was just your own judgement and instinct and safety and bring it home type of thing, not on the back of a wagon. I was driving with Brian and he had started I think three laps, did we do three laps, it was 11 laps, three, six, nine, that's right. Anyway, I was on my last stint, maybe it's the only stint, I can't remember, and I'm now coming in on my in-lap, and I am somewhere in the middle of nowhere, and I smoothed this again, and there was one corner which was a bit of a left-hander, and to keep it on the road really, and if I'd known of course I would have done, which I had the space to do it, I could have brought it back, but I just let it go up to the grass or the edge. And unbeknown to me, there was a rain gully there, and the suspensions were smashed down this rain gully and that was the end of us. Then of course the following year, Brian went off himself. It was very near the same area, if it wasn't the same corner. I thought it was in the same corner, but I'm not sure if it was or not. But he had his fiery accident there.

Is that the one where you weren't sure where he was?

Yes, we couldn't find out where the hospital was, and he'd been taken off by helicopter. There was no helicopter for me, but I suppose it wasn't needed. Maybe there would have been in one of them, I don't know, but I wasn't injured, so we took ages to get back to the hotel. Brian has had a big crash, he has caught fire, he has got burns, and he's gone to a hospital, there are loads of them. So Pedro and I, we went to try and find him but we didn't know where to go. We went from one hospital, they took us obviously to another one. I think it was about the third or fourth one we had gone to, so we found him and he was all bandaged up. His whole face looked like The Invisible Man. But Alain de Cadenet was in the same hospital, so obviously they knew which hospital they were going to take him to, but nobody could tell us. That's where the funny story about Alain helping Brian to have a pee, because his hands were all bandaged. It's a very famous thing. Alain obviously obliged in whatever way he could. His face still bears the marks, so he must have had two degree or three degree somewhere. His hands were quite bad for quite a while. That was a bad one, he was lucky really I suppose. It must have been he caught fire getting out of the car, and he was able to get himself out. Those were the days, and sometimes you can't get out.

It was an incredibly dangerous era. Did being around that change your outlook on life a little bit, generally speaking? I feel like being exposed to near-death experiences quite often would change your perspective on how you viewed life I guess. Did you stop and smell the roses a bit more, do you know what I mean?

I think you appreciated life, that's for sure. It's easy to say but not necessarily easy to do. There are times when you might think gosh, that was a close run, but you're in the game and you just have to accept it. You could probably slow down a little bit, but then you'll be slow, so then you won't get used any more. If you knock 10 miles an hour off the straight, going down the Mulsanne Straight, it's still going to be a huge accident. I don't know, you just home it never happens to you really. There are certain ways of driving that, you are conscious of it but it's in the back of your mind, it's not on the forefront of your mind. You get involved with what you're doing and it seems to minimise the thought process of whatever else might happen.

That makes a lot of sense. To finish up I was actually going to ask you a few quick fire questions, which I've got here. Single seaters or sports cars, if you have to choose between the two?

Today you are contracted really to Formula 1 aren't you? Quite how Hulkenberg managed to get into a Porsche. I don't understand that, there must have been agreement between two people I guess. That's how it is today. It's pretty restricted. We would just drive anything at any time, anywhere, because you wanted the money to fill the weekends up to make a good salary for yourself at the end of the year. I think it's more pure, a single seater is more pure, but really when you're driving a sports car, it becomes the same thing, really. Driving Goodwood, and you go through the chicane there, if you're in a right-hand drive car, which most race cars are, but the Cobras aren't, you just adjust, but it seems really, at the end of the day, it's similar to a single-seater, so what the hell is the difference?

Who was the driver you most admired?

Stirling was my boyhood dream because he won so many races that were completely against the odds, at the Nürburgring particularly, when Jack Fairman put it off the road, and he had to make up some unbelievable time to get back on the road, and he won the bloody race, so amazing. Schoolboy hero stuff, isn't it? It doesn't happen now. although, can do sometimes. But not like that. And his race, the Mille Miglia, I mean that is just unbelievable. That's the greatest motor race ever, isn't it? I am quite certain of that. But for me, obviously in my career, ultimately it was Clark without question, no question of doubt about that. There were probably more exciting drivers, but whenever we were in single-seaters as a group of drivers, let's say from 1964 to 1968, the question to your team was, what time did I do? Every other driver's next question would be, what's Jimmy done? Always.

Who do you think will win this year's F1 Drivers Championship?

I have to say it is getting more interesting. If you think back of how long we've had to wait, it's 20, 25 years, isn't it, since we had the supremacy of Schumacher, Hamilton, Vettel, really, you look back at that and you think. Grand Prix racing was forever, I mean watching racing unless you've got somebody you are following, you've got to have somebody to follow, and Senna was probably the last guy I would get out of bed for, and I did whilst in Australia. MotoGP is fantastic. You can see everything there and you know they're trying because they fall off, so you know they're trying. How they have that feel, I've never been a biker, but I've ridden bikes on the road, but they're just something else, but that's MotoGP.

It's almost like the car obviously isn't to Verstappen's liking at the moment. but I'm just wondering if it is the car or he's been knocked off his perch somehow. I don't know, it's interesting, because he was breezing it as he has done before, and it's a bit of a shock to the system, isn't it really? I think if I was a driver wanting to win it and with the best chance of winning it, it is still Verstappen because he is ahead, and Norris or anybody that is going to have maybe one DNF, and Verstappen is second or third, it's going to be enough to knock the stuffing out of the other driver I think. Not that it will, but mathematically it will. So Verstappen does still have the aces up his sleeve, if he could just hang it together, but there's an element of doubt now that wasn't there before, and funny things happen. He has been like a spoiled child in a way, because he's had the best toy, hasn't he? He is thorough, and he might have it deep in his thought that actually that bloody McLaren is better than my car. I don't know, but my money would be on Verstappen. But if somebody else won it, I think it would be good for the sport.

Final question, what is in your dream three car garage if you had to have three cars of your choice, what's going in there?

I suppose I did have a 917, but I would like a 917 again, but that will never happen of course. Going back to my past if you like, with my father and the garages, the favourite car that I loved as a teenager being driven by my father, was the DB2/4. I've got one and I've had it 60 years, so it's been there in the back of my mind all along. So that's the second car, and then another just cheap run around really. My wife's got the little Polo.

You know when I worked for Porsche, which I don't do any more, but when I was at the centre there, that PDK is just unbelievable. People talk about DSG, and DSG is good, but it's nothing like a PDK, it's fantastic. And to not have that technology in your road car. Actually the other car, if I'm not going to use any of them, would be an early 911, because that again takes me way back to when I was driving for them. The first 911 I ever drove, was it, yes, I think it was, it was a 1969 car, a 2.0 litre. I thought it was the fastest car ever invented, until I came up around Lake Geneva, I came across a 300 SL, and he just disappeared away from me, I was absolutely shell-shocked. Yes, but they were cracking little cars, and they were quite difficult to handle. They are modified now to be perfectly handleable, but in the early days, Porsche used to build under steer into the car, because they knew drivers would get into trouble with it because it wasn't an easy car to drive, and it wasn't. If you drive it fast, quickly, they would have an understeer tendency, particularly in the wet. It was a very satisfying car to get right, but now I don't know what they've done to them, but they're nothing like. I've driven the Porsche 911 there, but as soon as you get to a corner there is oversteer, straight away. It never used to be like that, you used to try and get rid of the under steer before you got to the other things.

Well Richard, thank you so much for taking the time and chatting, it's so lovely to hear the stories and everything. I think it's important as well for my generation because, I wasn't there, I didn't see it, so it's so nice to hear about it, and I really appreciate you taking the time so thank you very much.

Pleasure!

Oh no, you've run out of tape!