Renaissance Man: The Apex Interviews Sam Hancock

This week on the Apex our guest is racing driver, coach, writer, presenter, consultant and all-round motoring renaissance man Sam Hancock. After rising through the ranks of karting and single seaters early in his career, in 2001 Sam switched to endurance sports car competition with Kremer Racing. A career at the top of sports car racing followed, with a European Le Mans Series LMP2 Championship, a stint as a factory driver for Aston Martin Racing, a class win in the World Endurance Championship and seven outings at Le Mans all coming Sam's way.

Having tasted success while working with some of the world's most prestigious racing teams, Sam is also a full member of that most elite of gatherings, the British Racing Drivers’ Club. In this week’s interview he shares his fascinating insights on the historic racing scene, driving at the limit, and why the very best cars are always green...

Hector Kociak interviews Sam Hancock for The Apex by Private Collectors Club. Recorded and Produced by Jeremy Hindle & Demir Ametov. Transcribed by David Marcus. Edited by Hector Kociak & Charles Clegg.

We can get stuck into racing in a moment but for our readers who may not be familiar with you, the Sam Hancock of today is much more than a racing driver. You coach drivers, commentate for Eurosport, and do a lot of media and presenting work for things like Petrolicious and Collecting Cars. What prompted your transition into such a varied spectrum of car-related activity?

The need to make some money, quite simply! Trying to be a professional racing driver and getting paid consistently to do that job when you haven't made it to Formula 1 or similar heights is possible; there's plenty of roles and niche opportunities out there for pro drivers that don't get to that top step, but you have to really hustle, and you have to be versatile. You have to be open-minded to different ways of defining the phrase ‘professional racing driver’. It’s a process that I started an awful long time ago now.

When I was in sports car racing and just starting to get paid here and there, or at least have my expenses paid in my early 20s, I was constantly moving between raising sponsorship money and wearing a marketing hat on weekdays before donning a crash helmet at the weekends. You reach a tipping point of not having to take money to the teams to secure a seat, but your earnings are not consistent. You've got to be creative, and one of the ways that many drivers in that scenario earn a living is to do driver coaching. For some that means working at racing schools during the weeks and hopefully racing at the weekends. Alternatively it's working as a one-to-one private driver coach. Very often the client demographic is an amateur racer or ‘gentleman drivers’ as we sometimes call them, and you can build up long-term working relationships with those guys. I would say that everything that I do now starts with that driver coaching role, which itself was an extension of the pro driver, motor racing element of it.

Sam has had a lot of success at the Goodwood Revival in the glorious 1960 Ferrari 246S Dino prepared by Tim Samways' Sporting & Historic Car Engineers Ltd. Source: Sam Hancock

Speaking of racing, you've got a vast amount of experience with racing cars of all types and vintages. I've seen footage of you slinging an ex-Ecurie Ecosse Lister 'Knobbly' around Goodwood, battling in a Ferrari 246s Dino and of course competing in cutting-edge modern racing cars, not least in your seven outings at Le Mans. How does driving a vintage car on the limit differ from a modern racing car, and do you have a preference for the new stuff or the old stuff?

They differ enormously. In fact the stark contrast was brought right home to me the other day when I was doing a track test for Motor Sport Magazine, who were doing a feature on the new Endurance Racing Legends and Masters Endurance Legends series in the historic racing circles that cater for younger sports and GT cars with Le Mans history. We were testing a bunch of cars that are reasonably recent, roughly from 2003 to 2016, and it was quite interesting to be in such contemporary machinery when I spend most of my time now in historic cars. It was not only a lovely step back in time to what I used to know and love, but also a real reminder of the vast differences between the cars.

To answer your question: how do they differ driven on the limit? Let’s take a particular car, say the Lola LMP1 with a Judd V8 engine that I was testing the other day. That's a 2010s era car, very similar in fact to the Aston Martin Gulf-liveried LMP1 car that I raced at Le Mans. With those cars it is a bravery quest, if you know what I mean. It's how late you dare to brake, how much speed you dare to roll with into the apex, how early you are willing to commit to the throttle to keep corner speed up and activate the aerodynamic downforce which will give you the grip you need to rely on to make the exit. A lot of that is gut feel and experience, making lots of very quick little decisions subconsciously as you feel the car underneath you. It's a case of doing that with precision however, so it becomes a bit of a point to point exercise: the perfect braking point to the nearest metre, the perfect turning point connecting to the perfect apex, all while getting the right rolling speed. If you can string that together in a contemporary high downforce, high power, slick-tired race car, then you're going to put together a very quick lap time.

What it doesn't demand is what I would call a sense of feel, at least not in the way I define it. When I talk about a driver needing a sense of feel, I tend to think of an older car wafting in a four wheel drift from one side of the circuit to the other.

Something like a Lotus 49, Graham Hill style?

Yes, it could be, but it applies to cars of even lesser grip and older age than that. Frankly even younger stuff too. It could be a reasonably modern little Formula Ford or something on skinny tires, something that slides and drifts. In a lot of contemporary machinery, particularly prototypes and single seaters of a very high level, the cars have massive amounts of grip and are absolutely bolted to the road until the moment that they aren’t, and that moment arrives if you carry a bit too much speed into a corner or you load the car up in slightly the wrong way. You don't tend to get much of a slide, you definitely don't get a drift. You get a snap, and it's very hard to rescue that.

If you look at modern Formula 1, that's why you see the cars looking pretty vicious and difficult to control, and why you often see drivers just lose the back end out of nowhere. It's like they're on rails one moment, and then suddenly they're backwards into the wall a split second later, with no notice.

You have to feel sorry for Sebastian Vettel.

Yes, I do, because you can see that despite obviously having more problems than he used to have, you can see how hard the cars are to hang onto and how unpredictable they are. That is indicative of a modern race car in general. Current F1 perhaps represents an extreme of this character set that I'm talking about.

By stark contrast, older historic race cars have these lovely long drifts and slides. That's a very different sensation, and driving one of those on the limit demands a different kind of feel. I would say it’s less about courage; you're not braking crazy late and you're not rattling through the apexes at crazy speeds in blind hope that the downforce is going to keep you on the track through the exit. It's a constant sense of feel, and you need to be much more dialled into the nuances of the car as it communicates its needs and its movement through the seat and through the steering.

Older cars are moving all the time, even on the straights, even when you up shift in, let's say, a 1960s lightweight E-Type race car or something. When you depress the clutch to select a higher gear flat out on the back straight at Goodwood for example, the car gives a little wobble as you get a momentary weight transfer forward and aft. If you're not used to that and you're coming from modern single seater racing and sports cars exclusively, as I did about 10 years ago, it's weird, and it's scary: it feels like the car hasn't been bolted together properly, as if somebody forgot to tighten up a wheel nut or something and it's moving on the rim. That's how alien these historic cars can feel if all you know is contemporary racing cars.

Behind the wheel of the famous ex-Peter Sutcliffe Lightweight E-Type at the 2016 Spa Classic. Credit: ultimatecarpage.com

That's a very interesting explanation. I think there are also many car enthusiasts out there who fancy the idea of being involved in modern or vintage racing, but let's face it, we aren't all Ayrton Senna. Aside from obviously brilliantly fast drivers and deep pockets, what in your experience (including your time with Jota Sport), separates a great racing team from the merely good?

In the modern racing world money is important. It's probably the same in the historics as well to a certain extent. In modern racing a team needs to be well-funded, even if they are talented individuals in their respective roles as technicians or engineers or team managers. It takes a very rare group of people to perform amongst competitors if they haven't got a suitable budget.

Frankly just to get race wins under your belt at international level, the level of preparation has to be second to none, and reliability comes before performance. The old adage of ‘to come first, first you've got to get to the flag’ is true, and to prepare a car for, say, Le Mans and the rigours of 24 hours of intense racing, you can't leave anything to chance. You need a tremendous amount of budget for components which have a very restricted life. You're replacing things for new or rebuilding them on a very regular basis, probably being a bit too cautious with the kilometres per component that you're willing to put in, and you've got to have a lot of people. You want to have specialists in every area of the car's preparation. The bigger teams at Le Mans bring in an army of new, freshly rested mechanics and engineers at certain shifts during the race so that people don't get too tired. That is all part of the luxury of having a budget!

Competing in the Jota Sport Aston Martin V8 Vantage GT2 during the 2011 Le Mans 24 Hours. Credit: ultimatecarpage.com

So that's the first thing, but there are other ways of doing it. You mentioned Jota Sport, and it's a good choice. I was with them for about five years, fronted by Sam Hignett. Leadership comes from the top and he's brilliant, an outstanding team owner / manager. When I first drove for them in the Le Mans series many moons ago, I did a one-off round in their LMP1 Saitek. It was a really small team with a lot of volunteer workers (‘weekend warriors’ as they are not very affectionately referred to), but they were outstanding. That day in Istanbul Park in Turkey, we felt like the Davids taking on the Goliaths, and we did. There was an Audi and a Pescarolo on the circuit, some serious competition, and yet we were a bunch of guys from Frant in Kent. I think we were leading at one point, and I certainly remember handing the car over in second place overall.

There were maybe fewer than 10 people on the team that weekend, half of them volunteers, but they delivered, because Sam is very good at hiring great people, empowering them to do the job and giving them the tools that they need. Anything that the guys asked for, so long as it contributed to the car's performance, was granted. Anything that felt superfluous, whether it was a fancy pit awning or whatever, and didn't directly impact the car's performance or reliability, tended to be withheld. That was a good example.

Let’s talk a bit about ownership, which is something close to our hearts here at the Apex. I think you've mentioned elsewhere that your role as a car advisor often comes out of experience in coaching the relevant collector on track. Could you tell us a bit more about how various driving styles and levels of skill influence your recommendations?

Absolutely. Through my primary role as a driver coach, I work with a small number of amateur racers who take their racing very seriously. However, it's not their day job - they're doing it for fun. They've got businesses to run, families to spend time with and so on, what they want is to not waste their time. That means the car has to be reliable, it has to be enjoyable, and it needs to be prepared by people that know what they're doing. Inevitably as the relationship between coach and student develops, you end up talking a lot about what might suit that particular person in terms of their driving ability, the level that they're at, but also where they want to get to, and what events they want to do.

I've spent many a scary day in the passenger seat of high-powered race cars that have been sold to, let's say, unsuspecting buyers who are frankly just too early in their amateur historic racing career to be at the wheel of something as capable and as fast as some of these cars are. I remember one example in particular when somebody was in year one of their racing experiences and had been convinced to buy a replica GT40 and go do historic racing. That was a bad decision, based on bad advice, and frankly shame on whoever sold that car to the buyer. It was a dangerous bit of advice and ended in tears with a bit of a crash, and so everything had to be reigned right back in.

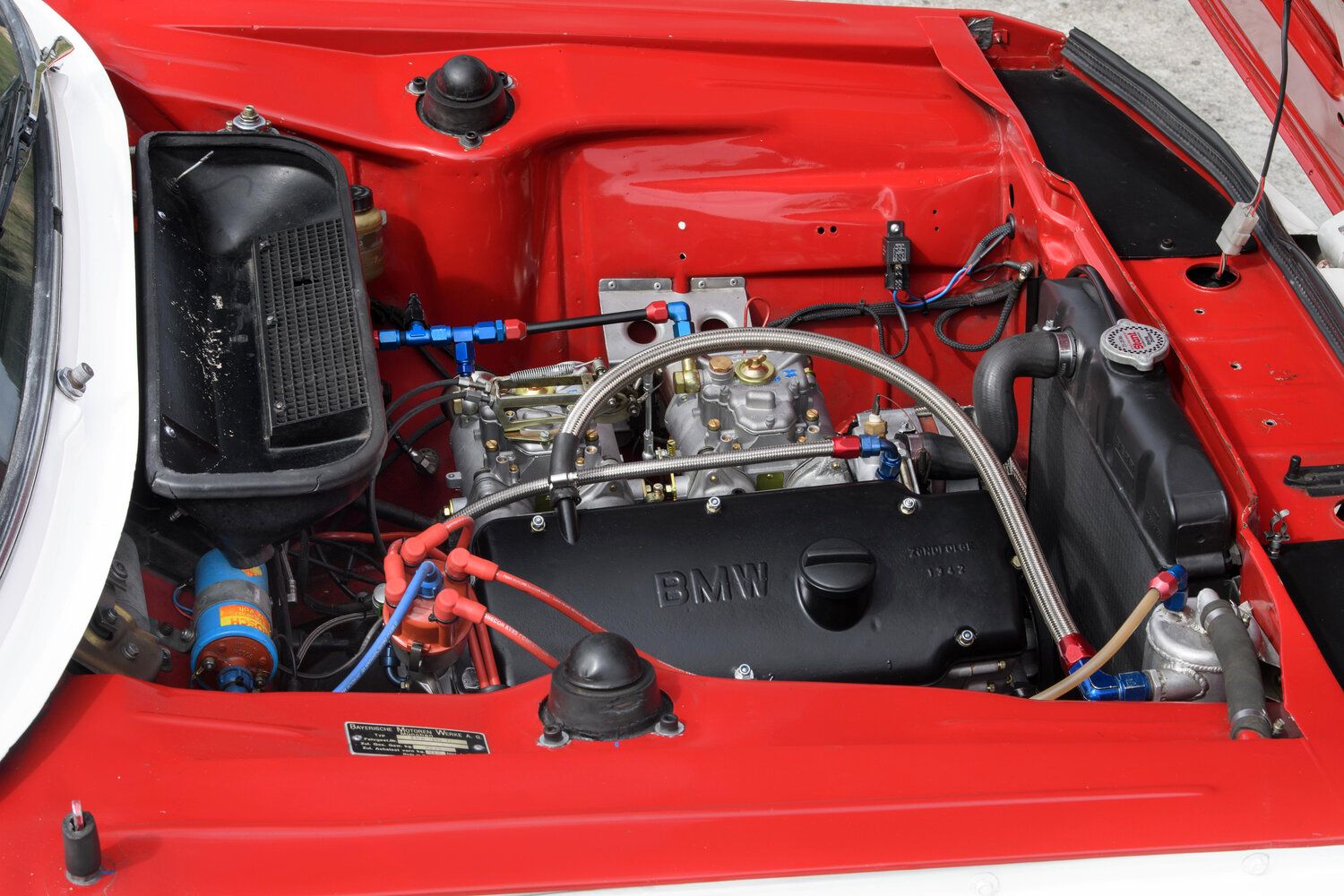

A great way to enter historic racing and typical of the sort of cars Sam tends to sell to his clients starting out in historic racing. 1964 BMW 1800 Ti (ex-Dieter Quester/Rauno Aaltonen, BMW Scuderia Baveria). Credit: Sam Hancock

I always encourage people that are setting out on their racing journey to spend time in more humble machinery, for example an sub-2.0 litre historic touring car, a Lotus Cortina or a BMW 1800 TI/SA, an Alfa GTA or GT Junior, something like that. Spend time in something that drifts and moves and slides constantly, but not at a crazy high rolling speed. You want to be feeling the tires slide across the surface, even in the slowest corners at 60 or 70mph. Then when you're trundling into Madgwick at Goodwood at 100mph and the car starts to move underneath you (as it definitely will), it's going to happen very progressively with lots of warning. It's going to be really manageable. I've spent plenty of time with total beginners on day one of their track experience in cars like that, and they love it. Even by the end of the first day, they can catch those kinds of slides and drifts and enjoy chucking the car around, and it all feels very fun and very safe. If you tried doing that with a beginner in something like a GT40, or anything equivalently inappropriate, what happens is that the speed at which the traction breaks is too high. If you don't have the experience to sense that moment coming, when it does arrive it all happens a bit too quickly, and it's so very easy to get it wrong and end up off the road.

My role as an advisor starts with my driver coach hat on and a gentle inquisition. Based on your experience or the kind of driving level that I'm experiencing from the passenger seat, and based on our conversations of the kind of cars and events that excite you, maybe try this or that car. Perhaps you're very early in your racing days but your dream is to race at the Goodwood Revival. Well good news, because whilst many of the grids at the Revival contain powerful cars that I wouldn't recommend, one of the best grids is the St Mary's Trophy for 1960s touring cars. Compared to other areas of historic racing, the cars are more affordable, and they're absolutely outstanding coaching cars. We can spend loads of time on the track together, and I can sit in the passenger seat safely and in comfort. We're in a big square three box tin can, there's a full roll cage and plenty of space for the two of us to sit side by side on a track day when we're doing some driver coaching. If you buy the right car it will be attractive to the selection committee at Goodwood who might be interested in having it on the grid. Those are the kind of conversations that we might have.

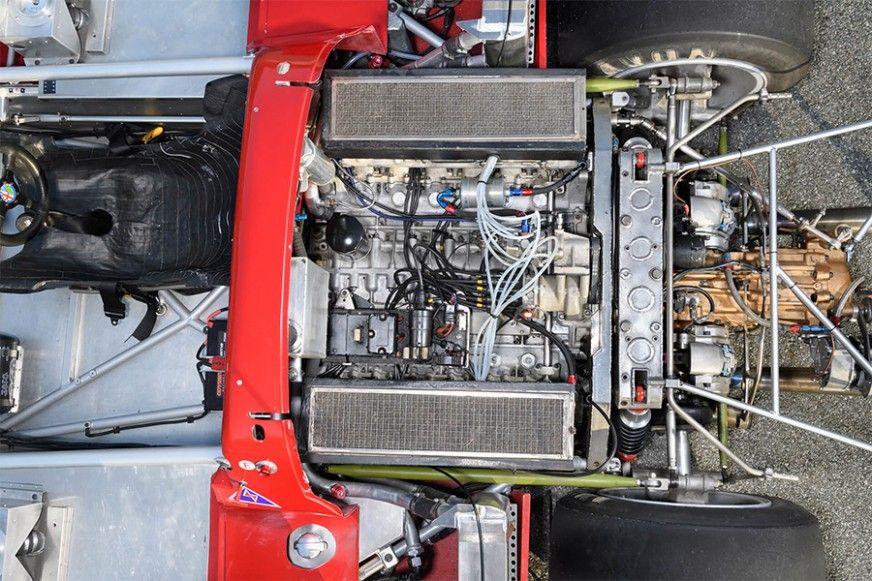

At the other end of the scale there are plenty of clients I work with who fell in love with racing through the ‘80s or ‘90s, for example, and are just obsessed with Group C. I've got one German client in particular who loves Silver Arrows Mercedes, the Sauber C9, the C11 and so on. Another one loves Porsche 962s, another one loves historic Formula 1 of the 1970s because that's the era that they grew up watching, falling in love with motor sport and that's when they set their hearts on their dream cars. What's nice these days is that all of these cars are eligible for something. You can actually go and buy them, you can race them and you can have a great time.

I think about it like climbing a ladder. You need to have a conversation that says: ‘I hear you, I love your taste, I love your ambition, I don't recommend this particular car for you today, because we need to do some work on your driving. I want you to get there, however, and by the way, those cars are not as scary as you might think’. In some cases the clients have got the budget that they need so it's more a case of ‘this year, why don't you think about buying this car and racing in it; let's get something a little slower but something that shares the characteristics of that Sauber C9 that you've dreamt of racing and owning one day’. You’ll get something that's less powerful but still runs on slicks, something that's got a little bit of down-force but not a lot, and just get used to the feeling over the next six to 12 months, and use that car as a springboard.

Following on from that, how mechanically minded does an amateur driver have to be to get the most out of their car, especially when it comes to vintage racing? Is spannering away an important part of the enjoyment or can you go without?

Most drivers (and I should probably include myself in this) don't know one end of a spanner from the other, to be honest!

Hah - I didn't want to be mean!

It’s not really a requirement. Some people do spanner their own cars and they'll prepare them at home and trailer them to the circuit, and you will see they will work terribly hard during the weekend doing all the necessary prep and maintenance between sessions. I tip my hat to those guys, because race weekends are tough, and focusing on driving sometimes can be hard enough. If you've got to spanner a car, you are probably on your own. You might have a mate there to help, but it’s a big job. So I'd say it's not necessary. 99% of the main historic racing scene is drivers who own the cars and race them, but who hire some kind of team or preparer to look after them. It gives them the luxury of just being able to arrive and drive on the race weekend.

It is important however to have some mechanical understanding and knowledge, particularly in historic cars. Less so in modern cars, actually, because the drivers are protected from the damage that they can inflict on the car through ill-timed down shifts or anything like that. There’s a limit to the damage you can do as a driver in a modern car, whereas in a historic car, you've only got to miss a shift or engage a lower gear too soon in the braking zone and you’ve over-revved the car. You can put a rod through the block and cost yourself tens of thousands of pounds in the blink of an eye, let alone lock the rear axle and spin the thing into the nearest wall. Having mechanical sympathy as a driver with regard to your inputs is critical, and to develop mechanical sympathy, you've got to have some mechanical knowledge and understanding of what's going on: how the car is propelling you forward or slowing down in the moment, and how your inputs affect the components at work throughout the process.

We spend a lot of time talking about this in coaching. Not going into nerdy detail, not necessarily needing to get on the spanners, but mechanical sympathy is key. Some of the cars that I get involved in are priceless museum pieces that have been restored and are then put out onto the race track; if you take an Alfa Tipo 33 TT 12 prototype for example, which won the world championship in the mid-1970s, you're not going to find many spare blocks if you put a hole in one, so you really need to know what you're doing to make sure you look after that engine! It’s absolutely critical, and I certainly prioritize that myself as a driver and spend a lot of time working with my clients as a coach to make sure they understand that too.

Sam's ex-Rowan Atkinson 1995 Ferrari 456 GT. Credit: Robert Cooper // Source: Classic Driver

That's a fascinating insight. On a more personal note, what's in your garage at the moment? Do you have a particular classic car that you have a strong attachment to or that comes with some good stories?

I only have one car, which is probably not to everybody's taste but I love it. It's a 1995 Ferrari 456 GT with a manual gearbox.

Not bad at all!

Yes! I mean, I love it, but I know many people don't find it interesting at all. I bought it a good few years ago now because I just felt that they were great value. I had always liked them. I have to admit when they were first launched, I didn't get it. To me as a teenager Ferrari was all about bright red fast racing and sports cars, and I didn't really understand this supposed flagship car that was launched in silver, looking really subtle and without lots of big bright yellow Ferrari shields on its flanks. As I grew older I started to appreciate it, and these days I think it's just coming into its own.

I really love the lines. I think it's very unusual, very pretty, and I think it's ageing very well. The car I bought is in my favourite colour - dark green. I've got an inexplicable obsession with green cars of any kind at the moment, humble or exotic, and I know that sounds really clichéd and like I’m jumping on the trendy bandwagon of green again...

Green and brown I think fall into that category...

Brown is a good one as well! I was talking about this the other day. I love brown cars, and I like to think that I was an early adopter on the green thing. I've had the 456 for quite a few years now and I got ridiculed by my brother Ollie when I first brought that home (!), but I think some people get it and some people don't and that's fine, that's the fun of cars. Each to their own, taste is subjective. Mine initially belonged to Rowan Atkinson, so he specced the colour scheme which is Verde Inglese, British Green over a pillarbox red leather interior. It's pretty out there, but I just love it.

Sam featuring in Kidston's 'Wolf of the Autostrada' film. Credit: Kidston

That does sound lovely. Talking more broadly about racing today and Le Mans, which I know is very close to your heart, in one of your recent interviews you came out quite strongly against criticism of amateur racers taking part in events like that. Why is the amateur gentleman driver so important to modern motorsport?

Ah, you've got me worried now, I'm trying to think of an interview I've done where I came out strongly against anything! Sometimes I do the commentary for the modern Le Mans 24-hours for Eurosport and you often find that when pro drivers are interviewed (not all and it's not often), sometimes they have a bit of a whinge about certain drivers out on track: that they don't know what they're doing, that they're all over the place, getting in the way, are dangerous, this, that or the other. Of course the drivers they're talking about are the amateurs, who are often referred to as gentleman drivers. I don't love that phrase to be honest, I think it's a bit dated, but the amateur contingent in sports car racing is the backbone of that entire strand of our sport. It always has been, and in fact the amateurs came first. The sport was in existence a long time before people turned professional.

So to moan about amateurs being an annoyance and getting in the way and causing trouble I think is a little bit short-sighted. At the same time, I totally get it. I've been in those situations myself as well, when you're fighting for a position or the lead and you trip up over an amateur driver. All I can say is that with the benefit of hindsight and a bit of context, I do think it's critical that amateur drivers arrive at these high level events suitably prepared and competent. If they are rushed there by their minders or their teams, that's not good news. It's dangerous for everybody and often doesn't end well. Let's take the wealthy guy who is put on a fast track to Le Mans and goes through a rushed process with plenty of people benefiting along the way from the size of that person's cheque book. What will happen is that they will go to Le Mans, they will be intimidated, maybe overwhelmed, and it may well all go horribly wrong. Maybe they'll have a spin, maybe they'll have a crash, maybe they'll collect somebody, maybe somebody gets hurt. Whatever happens, it doesn't give a good feeling to anybody and normally the person who is capable of writing those cheques leaves the scene with their tail between their legs, feeling very unimpressed with the whole thing.

On the other hand, if you actually just take a moment to be patient, plan properly and if everybody involved contributes the right amount of preparation and time, then you can turn that scenario on its head. You can end up with an amateur driver who is seriously knocking on the door of the pace of the pros, and able to win some of the amateur-accessible classes like LMP2 and GTE-Am. I've trained three LMP2 class winners over the years from very early in their career - in fact one had not done a single track day before our first day of coaching started! Fast forward four seasons and he's on the grid at Le Mans. Now that doesn't sound like very long, I know, but we had a plan, we had a structure, doing on average a day of coaching per week with lots of racing and background preparation as well. A couple of years later, he was on the podium as an LMP2 class winner. So it is possible to do it quickly, but only if you have structure, a plan, and only if you take it seriously.

A fantastic way of putting it, I think. Moving onto our final questions now, you're engaged with the car world in so many interesting ways - racing, presenting, brokering, writing - what's your advice for the next generation who might want to follow in your footsteps?

It depends what angle they're coming at it from, and what they might like to do. When I was growing up, all I wanted to be was Formula 1 World Champion like everybody else. Then you get that little bit older and you say okay, maybe World Champion is a bit ambitious, I just want to be a Formula 1 driver...

Ah, we've all been there...

Yes, I know how ridiculous it sounds, don't get me wrong. As I was climbing the single seater ladder I had to have a bit of a chat with myself at one point and accept that the F1 thing was not going to happen, but decided it would be amazing if I could just earn my living somehow as a racing driver. It doesn't matter what the definition of that ends up being, but I just wanted to be a professional racing driver and that's when I started looking at sports car racing and spent a lot of time battling to get into that world - and it paid off. Then as you get older again, you start to see that you constantly need to remain fluid and open to new ideas and possibilities.

I've been very lucky, and am so grateful that I gravitated into the world of historic racing, and that was by chance. My dad is a little bit involved in it, and some family friends (the Twymans) invited me to race one of their gorgeous little Lotus 11s at Goodwood. Frankly I had very little knowledge or understanding of historics at the time, but with knowledge and understanding comes appreciation and passion and a real love for the scene. I just hadn't had the exposure to it back then, but I was happy to do it. That started the whole historic thing and I loved it, I loved the people, I loved the different driving experiences of the cars and the romance of it. I was very lucky that the whole scene was going through a boom which hasn’t stopped yet, championed by the big events like Goodwood. This was before we had Le Mans Classic, before we had Monaco Historic, and before we had the huge travelling circus of prestigious historic races that we have now.

Testing an Aston Martin DBR9 at Rockingham. Credit: Robert Cooper // Source: Classic Driver

Even 10 years ago I sensed a certain momentum, and that I could add value to a lot of the owner drivers from a coaching point of view, help them set up their cars, and help them drive their cars better. Bringing my modern racing experience and that mindset into the historic world seemed really helpful to a lot of the people I was working with and was mutually beneficial. I decided to embrace all of it and I'm so relieved that I did. Everything that I do today and all of the racing moments that I cherish, the cars I can't believe I've driven and the experiences I've had are thanks to that. The fun we have when we go off on race weekends, the social interaction, and the friendships and relationships you build are just brilliant. It's extraordinary to think of it as work, and I know how lucky I am. I am truly grateful for it every single day.

So my advice to anyone that fancies doing something similar is grab onto any opportunity you possibly can that in any way relates to this space and this racing scene. If that's behind the wheel of something, good for you, but if it's sweeping the floors and making the teas at a race preparer or a restoration workshop or a classic car magazine, do that too. My first visit to Le Mans wasn't as a driver - it was as a runner for a TV company, and even that job only came about when I was already there and had driven down with a tent and no ticket!

Chat to people, put yourself out there. Don't be forceful but do be enthusiastic, and just keep dropping onto people's radar on a semi-regular basis because one day they'll say, oh yes, good timing, you could help us with this or we just need another pair of hands on that. From those starting points, you will build relationships that eventually will generate a journey or a route map to where you want to be.

That's brilliant. I can hear the passion in your voice when you describe that. It makes me want to get up and run to the nearest workshop!

1974 Alfa Romeo Tipo 33 TT 12. Credit: Girardo & Co.

We’ll end on some quick fire questions. The first one is: of all the cars you have driven, which was the most memorable or impressive, the one that made you perk up and just go ‘wow’?

That's a really good question. There have been so many which have impressed in different ways, but it’s one I mentioned earlier, the Alfa Tipo 33 TT 12. It's not the best handling car in the world, but for sheer presence it's got to be right up there. It's an extraordinarily evocative sports prototype racing car, and the moment it made me sit up and go ‘wow’, was the first time I accelerated out of the pit lane on its first shakedown after restoration.

It was the noise, that unique, unusual soundtrack from the flat-twelve boxer engine. It makes the hairs on the back of your neck stand up and your spine tingle. To experience it from the driver's seat took me back to countless documentaries I'd watched through my childhood about historic racing, and I just felt teleported back to the 1970s. Suddenly I could feel and hear this sound that I've never experienced in another car.

Second question: favourite race track?

Monaco, by far.

That's very interesting, because most people we’ve interviewed have said Spa or the Nürburgring. I think this is the first Monaco we've had.

I get Spa and the Nürburgring. Spa is a great track as far as traditional race tracks go. The Nürburgring is an insane roller coaster. I've never raced there but I've been around it many times. I love it, I would love to race there and if I did, who knows, maybe I would think of it suddenly as my number one.

But by far the best track experience I've ever had was in a 1976 Fittipaldi Formula 1 car with a Cosworth DFV engine in the Monaco Historic Grand Prix. That circuit for me is as good as it gets. There's just something incredible about racing a car around there at those speeds. It feels brilliantly wrong for a start, and the speed is amplified by the proximity of the Armco barrier. You've got a really wide variety of corners. I know that some people might look at the tight technical corners and think it's slow and boring, but it's not - even the tight hairpins are still challenging when the Armco is so close. Then suddenly you're into the tunnel or something which in a 1970s F1 car is a really quick right hander, and it's not flat. This is not a kink on a straight - this is a real corner, and the car is drifting, and it's hard to pick your apex and then you explode back into the light and it’s a quick piff-paff through the chicane with the sea and the boats on your left...

The whole thing is utterly unique and when you're there, hearing the engine noise bouncing off the walls and the buildings, it just takes you to a higher level. You just don't get close to it with the same kind of a car at a traditional circuit like Silverstone, or even Spa.

That sounds like a dream. Final question: what lesson or lessons have your life experience in motorsport and the car world taught you?

Crikey, lots I'm sure! I try very hard to stay grateful for it. It's very easy to get complacent with a lot of this stuff when you're doing it week in and week out. But also to just keep pushing because particularly in a career like this, where everything we've discussed sounds really appealing and a little bit glamorous, the reality is that much of it is not. Behind the scenes it is and has always been a lot of hustle, and there is lots of heartache when you lose momentum, or you don't have a seat or sponsorship money that you needed. There's definitely a lack of job security and over the years that's why I've branched out into these other areas; each of those is hard at first, and then you build a bit of traction, and momentum builds and you roll with that. So yes, I suppose the other lesson is just keep pushing, because if you do, something will give in your favour soon enough, and then you're off to the races - hopefully literally.

I think that's a great note to end on. Sam, thank you so very much for speaking to us today, and for giving us such a fascinating insight into your world.

My great pleasure, thanks for having me.

To get in contact with Sam for driver coaching or to see his fantastic selection of race cars in stock, please visit https://www.samhancock.com/.