Our Top 10 Greatest Le Mans Moments

The 24 Hours of Le Mans is quite simply the greatest motorsport endurance event on the planet, and one of the most prestigious races in the world. Save for periods of global conflict and the odd strike, for close to a century the Loire valley has echoed every year with the sounds of the world’s most advanced racing machines vying for glory. A test bed for modern automotive technology since the first edition held in 1923, the sweeping curves and long straights of the Circuit de la Sarthe are also the setting for compelling feats of endurance and bravery by star drivers from across all classes of motorsport, for whom racing at Le Mans is a privilege and an honour.

The 2020 edition of the 24 Hours of Le Mans takes place on 19-20 September, marking the second autumnal race in its history after 1968. In celebration of the race and following last week's vivid tales of Le Mans from Peter Sutcliffe, the Apex team looked back through the archives to bring you our Top 10 Greatest Le Mans Moments. There are many more to choose from - so let us know what would have made your selection on our Twitter or Instagram!

Written by Hector Kociak. Edited by Charles Clegg. Produced by Demir Ametov.

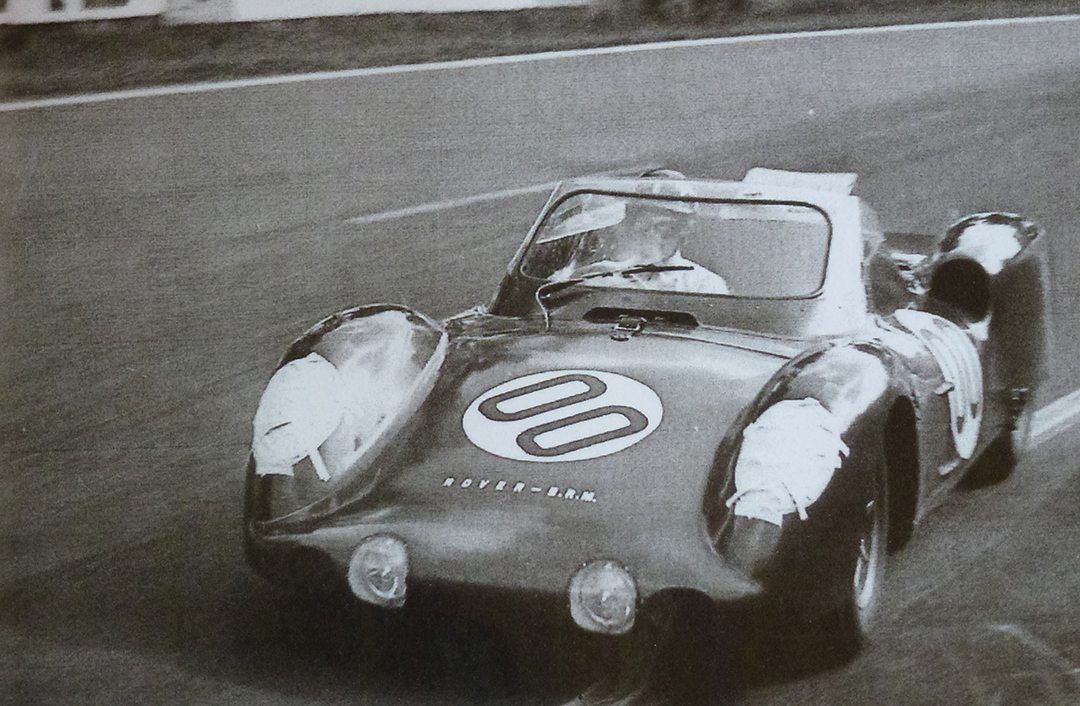

1963: The Rover-BRM Gas Turbine Car Debut

"You’re sitting in this thing that you might call a motor car and the next minute it sounds as if you’ve got a 707 just behind you, about to suck you up and devour you like an enormous monster." Such was Graham Hill’s take on the Rover-BRM, a prototype gas-turbine powered racing car built on a BRM F1 chassis which debuted at Le Mans in 1963 to much curiosity from the world’s press (and some irritation from Ferrari, from whom it stole many a headline). Despite a button in place of a gas pedal and 2-3 seconds of engine lag, the experimental vehicle somehow survived to the end of the race under the expert direction of Hill and Richie Ginther.

The car performed admirably on its debut, topping out at 140mph on the Mulsanne Straight and putting in a performance that would have secured 8th place from a petrol-powered racing car (and all at a regal 6.97 mpg of kerosene). Hill would race the car again in 1965 in coupé form alongside Jackie Stewart to less success, with early damage to the turbine blades requiring the car to be detuned for survival from an already middling 150bhp. “A long and winding road,” Stewart was reported as saying, “it felt like a lot more than 24 hours...”.

Aside from showcasing the Rover-BRM in all its whispering glory, evocative footage of its 1963 debut from British Pathé will be of interest to any historic racing fan, featuring Stirling Moss in a very ‘off-duty’ beard, a groovy 1960s soundtrack, and some merciless ribbing from the British Pathé voiceover artist (“...he’s a little bloke, Riche Ginther, so he takes his own seat with him when it’s his turn to take over and edge out into the 8-mile course…”). It is certainly worth a watch.

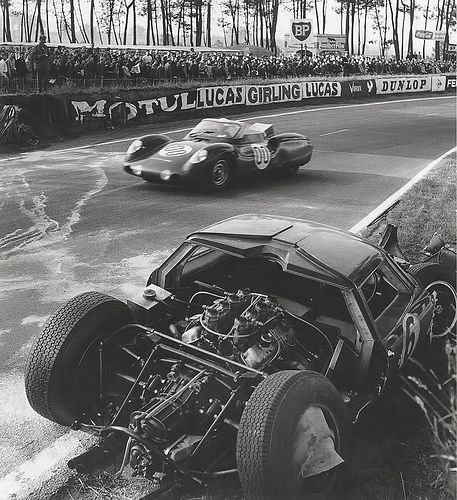

2012: The Nissan Deltawing Repair Attempt

Great moments at Le Mans aren’t always daring passes or happy celebrations on the podium. Sometimes it’s the small incidents captured on camera which show the spirit which drives men and women to persist at the Circuit de la Sarthe.

In 2012 the unique Nissan Deltawing, designed by Ben Bowlby and permitted to run at Le Mans under the Garage 56 initiative for experimental vehicles, was being driven by Satoshi Motoyama when it tangled with Kazuki Nakajima’s Toyota TS030 Hybrid at the Porsche Curves. A hard impact with a concrete barrier later, the Deltawing lies silent and heavily damaged by the side of the track. The crowd expects a retirement - but Motoyama runs over to the chain link fence, where a group of Nissan engineers has appeared. The pit entrance is just up the road. If the car can return there under its own power, it can be repaired. The race isn’t over yet, and there is still hope.

For two frantic hours Motoyama works with tools passed to him by the engineers. As light fades, the truth becomes clear. It is not enough. The camera lingers on crew chief Darren Cox clasping a broken Motoyama’s hands through the fence, before the driver tearfully abandons the wreck and passes through an exit gate to applause from the spectators. Nissan did everything they could - but sadly their race was over.

1999: Mercedes-Benz CLRs Take To The Skies

Probably the last thing you want to hear as a Mercedes aerodynamics engineer listening to the Le Mans commentary feed is the words “my God, the Mercedes has taken off!”. Unfortunately this was the case at Le Mans in 1999, when the Mercedes-Benz CLR driven by Peter Dumbreck clipped an apex kerb on the straight leading to Indianapolis while in pursuit of Thierry Boutsen’s second-placed Toyota. Watched by a huge global audience on live television, Dumbreck’s car immediately took off into the air, flipping end-over-end three times at a height of nearly 15 metres before landing in the trees to the left hand side of the track.

Incredibly, fellow AMG-Mercedes driver Mark Webber had suffered two similar accidents in warm-up and practice earlier in the week. Dumbreck was briefly knocked unconscious by the impact but did not suffer any injuries; the remaining CLR was immediately withdrawn by the team and the entire racing programme terminated shortly thereafter. The image of flying CLRs has passed into Le Mans history; a salutary reminder of how racing at Le Mans pushes machinery up to, and sometimes beyond, its limits.

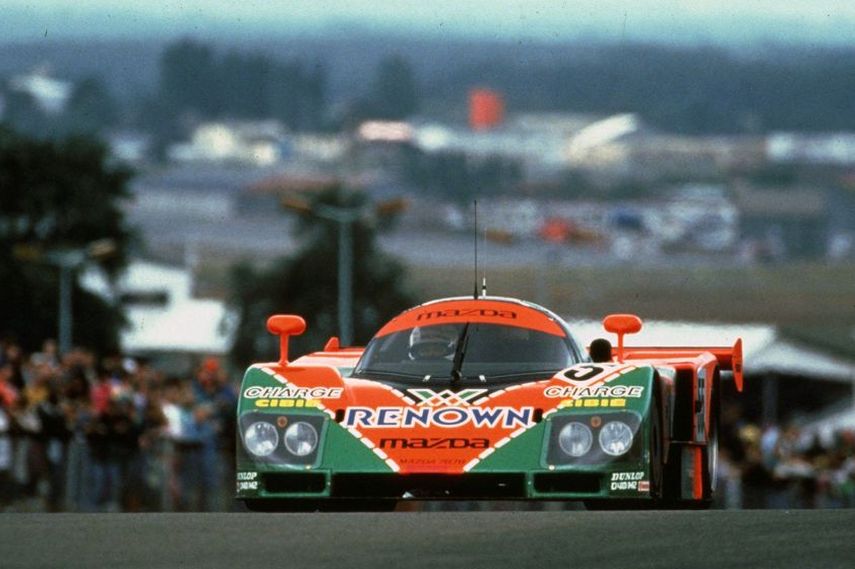

1991: The Iconic Mazda 787B Wins For Japan

1991 was a year in which Mazda made history. The Mazda 787B, powered by a 700hp 4-rotor Wankel rotary engine, not only beat the might of the Jaguar XJ-12 and the Mercedes-Benz C-11 (which would gain pole position, and record highest trap speed and fastest lap of the race set by a certain M. Schumacher at 3:35.564), but became the first Japanese car to win the 24 Hours of Le Mans. The thrilling sound of the rotary engine at full throttle and the outrageous green and orange livery of car no.55 (honouring Japanese clothing manufacturer and team sponsor Renown) captured the imagination of racing fans around the world, although the victory had been a close run thing - it was only at the 22nd hour of the race that the the 787B took the lead, having relied on exceptional fuel economy and higher cornering speeds to eke out a winning margin over its competitors.

Almost 20 years later, the car driven by Johnny Herbert, Volker Weidler and Bertrand Gachot continues to attract fans as one of the most beloved exhibits at the Mazda Museum at Hiroshima, as well as making multiple appearances in Gran Turismo, the cult driving simulator series from Polyphony Digital.

2017: Kamui Kobayashi Obliterates The Le Mans Lap Record

During the second qualifying session for the 2017 edition of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the no.7 Toyota TS050 was already on pole, with Mike Conway having put down a formidable 3:18.510 before red flags were raised after the crash of the no.33 Euroasia Motorsport LMP2 car. However that was not good enough for Kamui Kobayashi, who went out after the session restart on fresh tyres to a tailwind on the Mulsanne Straight and a clear track, and proceeded to hammer home one of the most extraordinary laps in Le Mans history. His time of 3:14.791 was 2.096 seconds quicker than Neel Jani’s previous lap record in the Porsche 919 and the fastest time since 1989 (when the chicanes were added to the Mulsanne Straight).

To put this into perspective, Kobayashi’s pole time was a tenth of a second quicker than the 1985 pole time, set by Hans-Joachim Stuck in a Porsche 962C on a circuit with four fewer corners than the modern layout. Watching Kobayashi’s LMP1 car go round the circuit as if on rails is pure pleasure; here we share footage from Sam Hancock on Eurosport, who witnessed this extraordinary lap live from the commentary box.

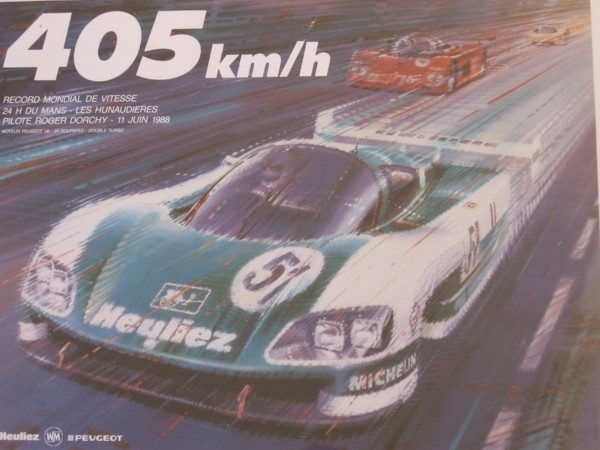

1988: Roger Dorchy’s Speed Record In The WM P88

Shortly before 8.46pm on Saturday 11 June 1988, WM Peugeot engineer Vincent Soulignac sent a radio message to team driver Roger Dorchy, about to embark on another lap of the Circuit de la Sarthe. The command was simple: to increase the boost pressure of the twin-turbo PRV V6 engine of the low drag, low downforce WM P88 racing car by 100 millibars. With 910bhp at the driver’s disposal it was time to push for 400km/h down the Mulsanne Straight.

Shortly afterwards, Dorchy shot through the Mulsanne speed trap at 407 km/h (252.989 mph). Route Nationale 138 had never seen anything like it; a particularly impressive time for a team with no full time members running a car built in the garden workshop of Gérard Welter, the man responsible for the Peugeot 205. Peugeot management were overjoyed, and it was quickly agreed that the record should be reported as 405 km/h to coincide with the release of the Peugeot 405. The Sauber-Mercedes team challenged the record in 1989 but failed to beat it; the addition of the Mulsanne chicanes for the post-1989 layout has meant that no team has come close since.

The WM P88 retired shortly after the record run with turbocharging, cooling and electrical issues. However the goal of ‘Project 400’ had been achieved. We have only one question - could it have gone even faster?

1927: Victory For The Bentley Boys

W.O. Bentley was not a great fan of endurance racing, having called the idea “crazy” when it was first suggested to him. A Bentley victory in 1924 changed his mind, and the 1927 edition of the race saw the Bentley legend made in the public eye as victory was snatched from the jaws of defeat by the brave actions of a dashing playboy or two. Following an enormous crash at La Maison Blanche which took out the Callingham and Duller works Bentleys, racing journalist Sammy Davis arrived at the scene with a crunch, helping his compatriots out of danger before limping his damaged 3.0 litre Bentley Super Sport back to the pits. Davis and his co-driver, Harley Street specialist Dr. Dudley Benjafield, went on to catch the leading car in the thrilling final hour of the race to take the chequered flag, returning home as national heroes alongside their winning car, ‘Old No.7’.

The 1927 victory marked the first of four years of consecutive wins for the colourful group of adventurers and racers (including Woolf ‘Babe’ Barnato and Sir Henry ‘Tim’ Birkin) who came to define the glamour and romance of British motorsport in the roaring twenties. Their legend lives on today, both in the Bentley marque and the vivid imagination of many an amateur racing driver.

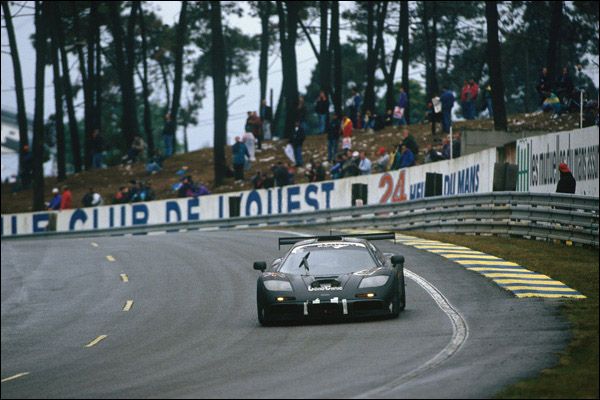

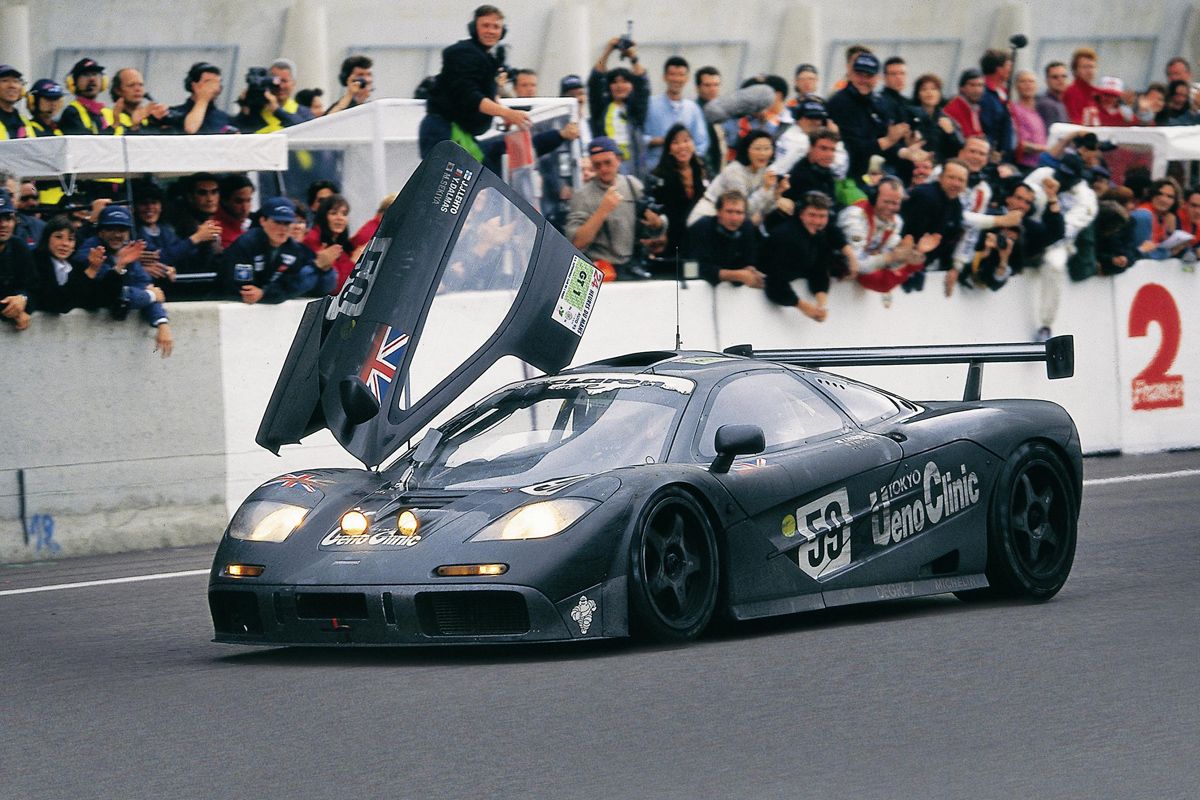

1995: First Time’s A Winner In The McLaren F1 GTR

You are not supposed to be able to turn up to the 24 Hours of Le Mans with no experience and take overall victory on your first attempt, with a car not originally designed for the job, in a 16-hour downpour. But that is what McLaren did in 1995, sweeping away all competition in the GT class to take a stunning overall victory in which four of the first five places were held by F1 GTRs.

The F1 was never meant to be a racing car, let alone an endurance racer. Gordon Murray’s test for it was whether you’d want to drive it to the South of France, rather than any sort of track aspirations, and only customer pressure had made McLaren finally relent and provide an endurance racing kit for the car. On the day, smart driving and reliability management, and some extraordinary night-time heroics behind the wheel from La Sarthe rookie JJ Lehto in the no. 59 Ueno Clinic F1 GTR were enough to secure a shock win and cement the reputation of the McLaren F1 as a superior machine, both on and off the racing circuit.

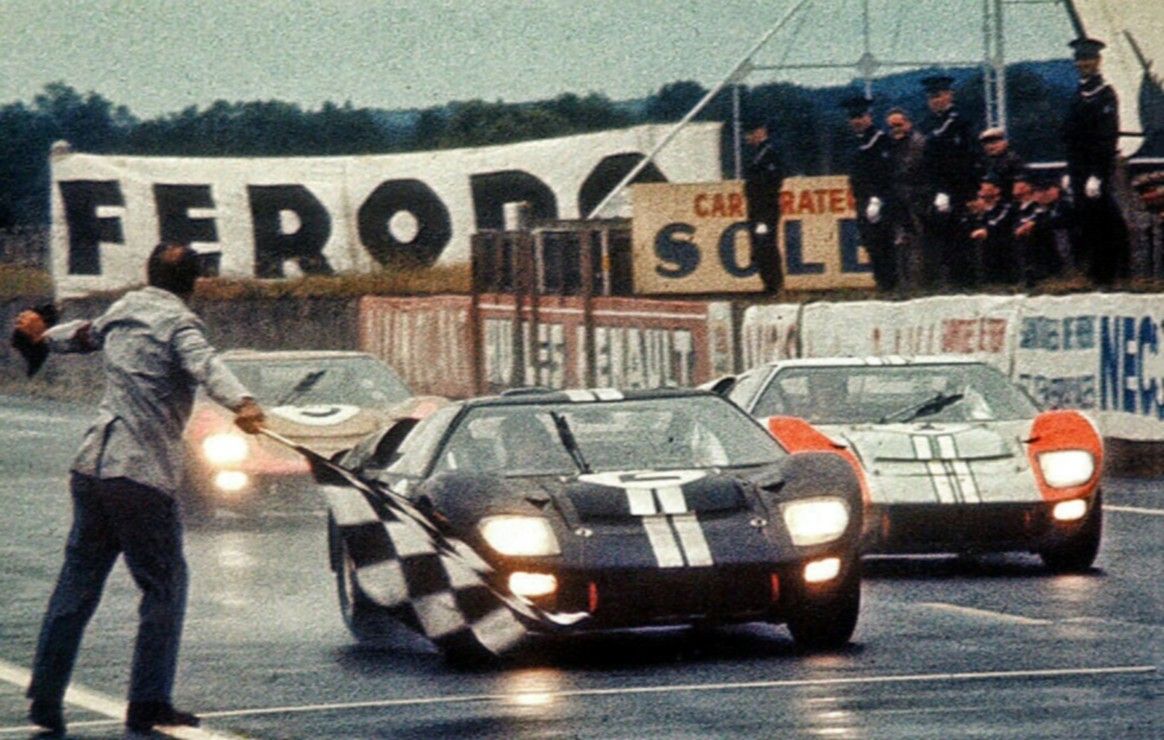

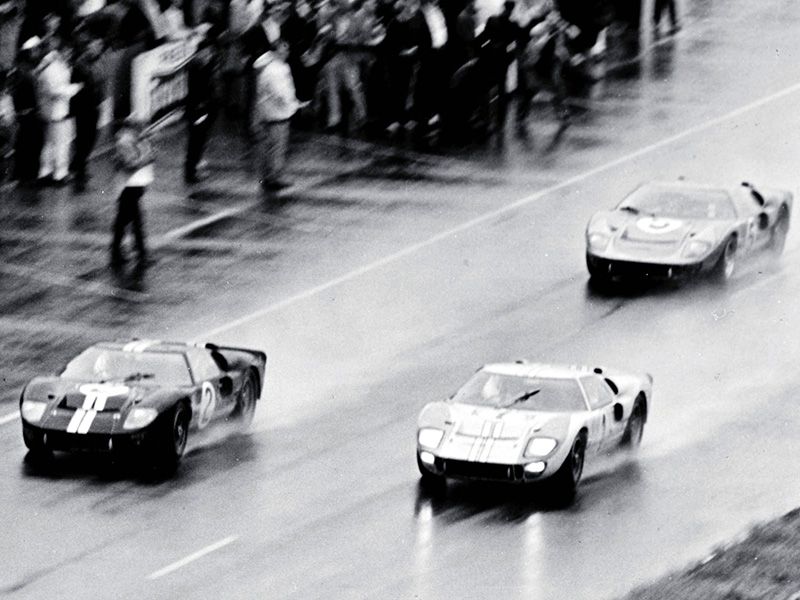

1966: Ford’s Foul Play Photo Finish

The glum faces of Chris Amon and Bruce McLaren on the podium said it all. Ford had finally swept away the competition with their GT40 MkIIs and achieved victory at Le Mans after years of attacking the dominance of Ferrari. But there was a price to pay. As the challenge of the Bandini/Guichet and Scarfiotti/Parkes Ferraris had disappeared during the race, and the privateer Ferrari teams were whittled down by retirements and accidents, Ford racing director Leo Beebe had relayed team orders to the leading Ford driven by Ken Miles and Denny Hulme. It was time to slow down and give Ford an iconic marketing shot: two winning GT40s going across the finish line at Le Mans together.

Unfortunately, despite the dominance of the Miles/Hulme car towards the end of the race, the McLaren/Amon car had covered a greater distance due to starting slightly further back. According to the race rules it therefore took the win. The order to slow down was a controversial move by Ford racing management to say the least, which denied Ken Miles the triple crown for wins at the Daytona 24h, Sebring 12h, and Le Mans 24h races - a crown he would never again race for, due to his premature death in testing in August 1966. Ever since the photo finish incident, Ford have been accused of throwing Miles’ win away for the sake of good publicity. But as the saying goes - win on Sunday, sell on Monday...

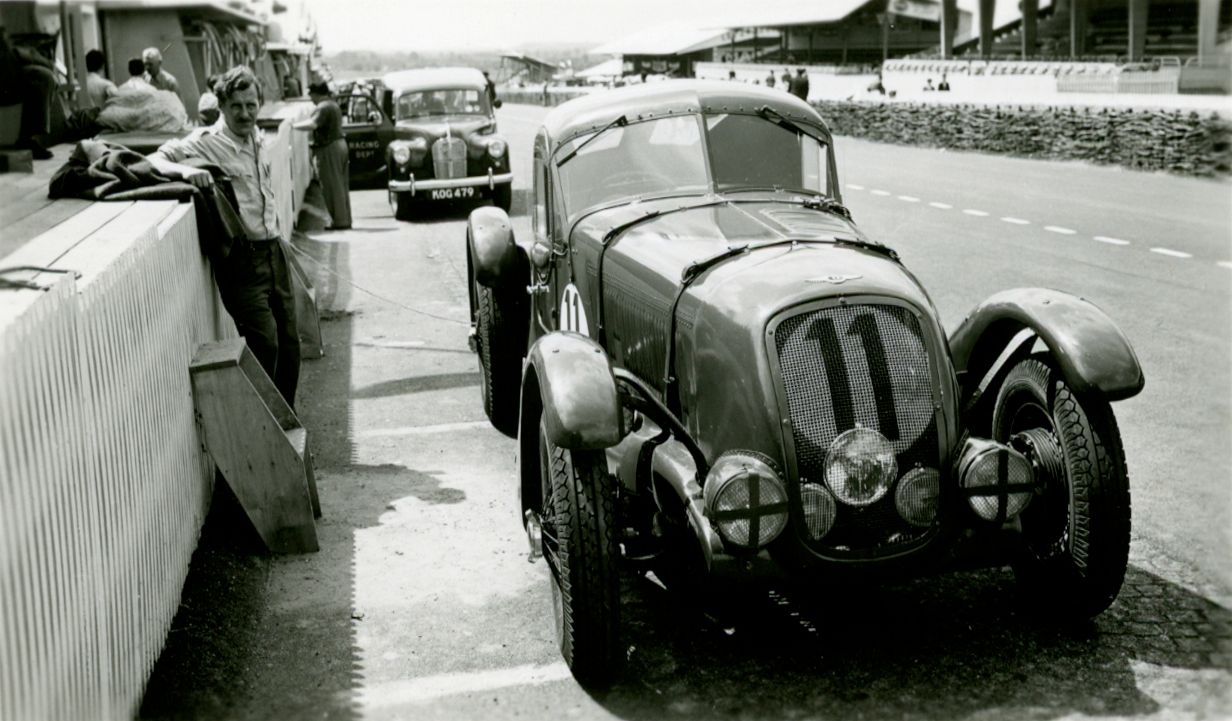

1950: Eddie Hall’s One Man Race

Raymond Sommer, Luigi Chinetti, Pierre Levegh; these were all drivers known for epic feats of endurance behind the wheel. But Edward Ramsden Hall, bobsled Olympian, mountaineer, figure skating photographer and amateur racing driver went one better than all of them.

Having dreamed of entering Le Mans in his 4 ½ litre Bentley for years, and having endured a race cancellation in 1936 due to strikes, on the eve of his 50th birthday Eddie finally found himself on the grid with no distractions. While he had a co-driver in Tommy Clarke, there would be no need for Tommy’s services on this occasion - because Eddie went on to complete the entire 1950 edition of the 24-hour race himself, becoming the first and only person to do so. The sight of an aged Bentley with a fabricated hard top and touring lamps roaring under the rebuilt Dunlop bridge with the throttle pinned must have been quite something to witness. And whether it was supernatural endurance, sheer grit, or just the conviction that he’d waited damn well bloody long enough for it all, Eddie’s driving feat is one that deserves to be remembered.

To follow the 2020 Le Mans 24 Hours visit the official website at https://www.lemans.org/en/24-hours-of-le-mans.