Lights, Camera, Traction: Behind The Scenes Of Our Favourite Car Movies

As the cold autumn rains sweep in and the excitements of Le Mans and the Nürburgring 24h fade into recent memory, The Apex team finds itself at home sewing patches onto race suits, leafing through the classifieds and daydreaming of our next drives. The world of film provides ample inspiration in times like these, so this week we take you behind the scenes to reveal some of the curious tales and interesting facts from our favourite automotive movies.

Written by Hector Kociak for The Apex by Private Collectors Club. Edited by Charles Clegg. Produced by Demir Ametov.

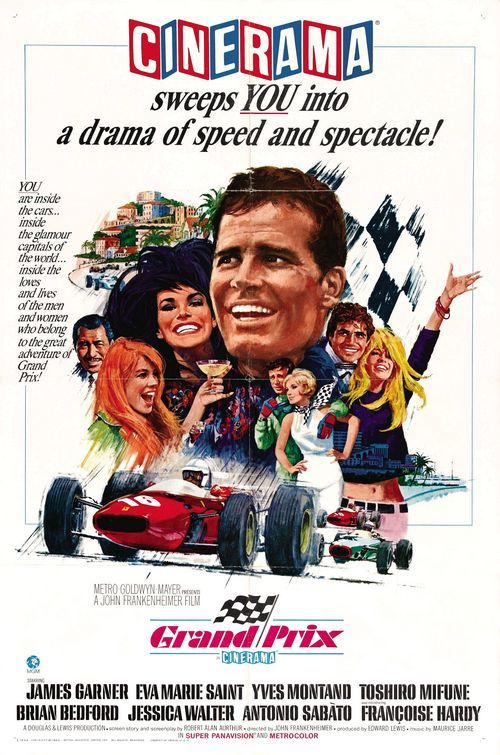

Grand Prix (1966)

From the moment Saul Bass’s title sequence begins, you know this is the racing film you’ve been waiting for. The words “Grand Prix” emerge from the darkness of an exhaust pipe; close-ups of tyre tread and carburettors cascade across the screen as the cacophony of engines rises. For many, Grand Prix is one of the great racing films, with its combination of a soapy, yet coherent plot (not guaranteed in car movies) with extraordinary track footage. Director John Frankenheimer wanted realism and authenticity, and with over ten million dollars to play with, that is what Grand Prix (for the most part) got - along with three Academy Awards in 1967.

The film was shot at actual Grand Prix venues, mostly during race weekends, with real footage cut seamlessly into the film. The names and helmet designs/car colours of the racers were chosen to be close to the real drivers so that this could be done with ease (Aron/Chris Amon, Sarti/John Surtees, Barlini/Lorenzo Bandini, Stoddart/Jackie Stewart). A number of F1 stars of the day such as Graham Hill, Jochen Rindt, Bruce McLaren and Phil Hill had multiple cameo roles.

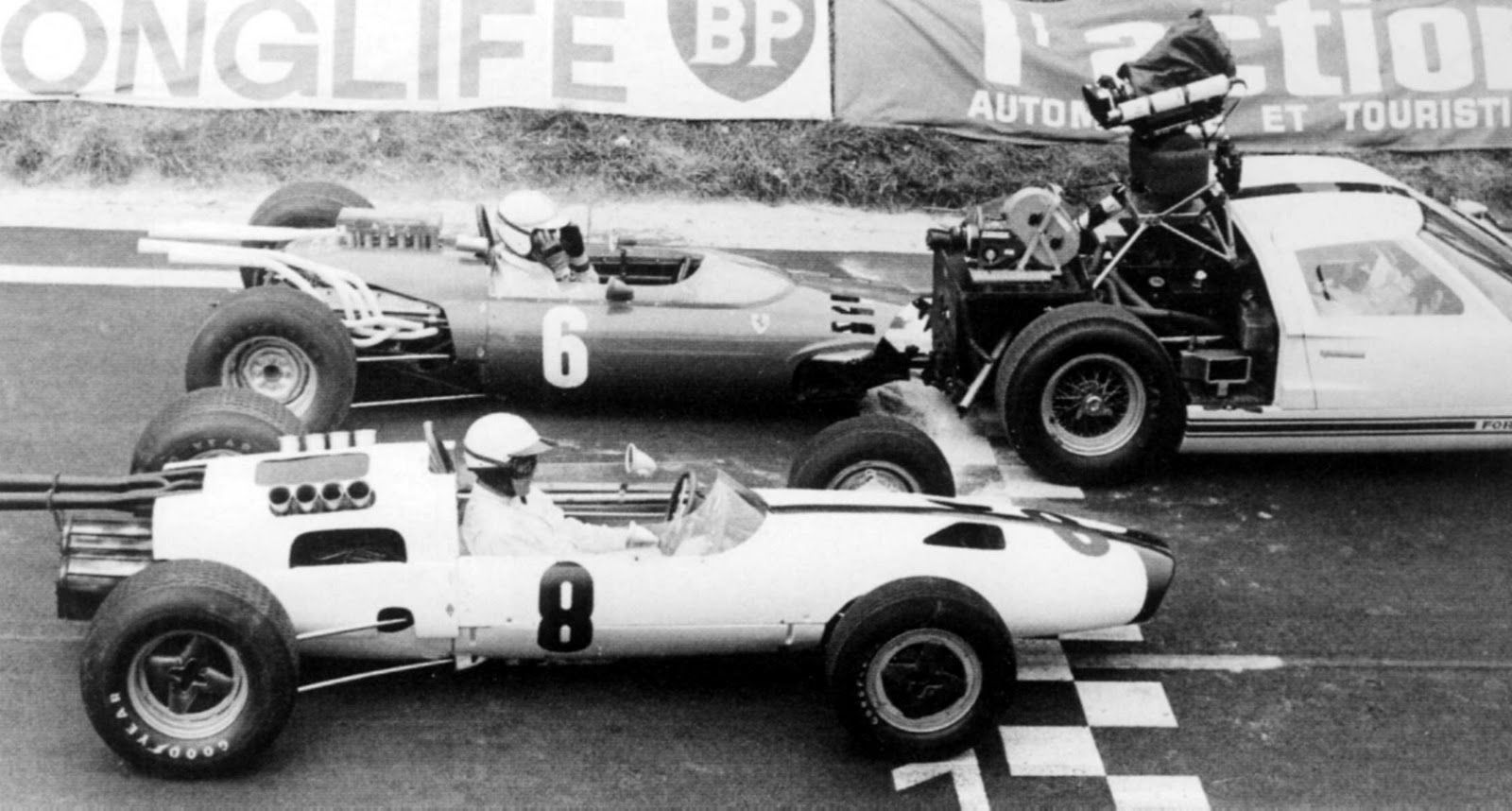

The cars themselves were Formula Juniors mocked up to look like F1 cars, and were driven by the actors as far as possible. Some of them did not hold licences however and preferred to be dragged along behind a GT40 camera car in a rather suspect two-wheeled sled. However no race footage was sped up. Lead actor James Garner was even praised for his natural driving talents, and would later run a Corvette racing team of his own (American International Racing).

On set of Grand Prix. Source: Classic Driver

The astonishing shots in the film were captured on state-of-the-art Panavision cameras using 65mm reel, suitable for immersive IMAX-like Cinerama theatres. Due to the G-forces produced by the cornering cars, Panavision had to develop precision engineering solutions to allow the cameras to operate without distortion. Systems originally developed for missile testing telemetry were deployed in the remote controlled cameras to capture the spectacular and detailed shots of the final race at the Monza banking (which in real life had not been used for Formula 1 racing since 1961).

Steve McQueen was originally approached to star in Grand Prix, but did not gel with producer Edward Lewis; while McQueen was later disparaging about the film, his Le Mans is clearly indebted to it. Grand Prix remains a classic of the genre - and we would defy anyone watching the sequences at a rainy Spa to claim otherwise.

Bullitt (1968)

Flying hubcaps, roaring V8s, and staccato impacts of suspension bottoming out on steep San Francisco streets: it could only be Steve McQueen’s 1968 classic Bullitt, the story of grizzled detective Lieutenant Frank Bullitt fighting his way through a confusing web of Chicago mob intrigues. The chase scene where McQueen’s highland green 1968 Ford Mustang Fastback tails a Dodge Charger is eleven minutes of muscle car bliss. It won Frank P Keller an editing Oscar in 1969 and has gone down in cinematic history, despite amusing continuity errors, mysterious double-declutching, and an unrealistic number of flying hubcaps.

But it isn’t just editing trickery which makes the scene special. To make things visceral and realistic, McQueen and stunt drivers Bud Akins and Bill Hickman reached speeds in excess of 100mph; the inevitable slip-ups gave the editor some brilliant footage. The Dodge Charger really does crash straight into the camera at one point, the violent suspension impacts are real, and McQueen famously overcooking a turn and lighting up the Mustang’s tyres in both directions, while dramatic, was not intentional (and prompted Bud Akins to take over the Mustang stunt driving).

A great short documentary about the making of Bullitt which includes the footage of the Dodge Charger crashing into the camera at 8 mins 15 seconds.

Amusingly, despite wrenchman Max Balchowsky giving the Bullitt Mustang improved suspension, Koni shock absorbers, milled heads, an aftermarket ignition system and a reworked carburettor, the stock Dodge Charger was much faster than the Ford; the stunt drivers had to feather the accelerator to prevent it from peeling away. The sound of McQueen’s car was also overdubbed in production with GT40 engine noise. However none of that prevented the ‘68 Mustang GT 390 Fastback from becoming an instant classic in its own right, with the actual film car selling most recently at auction for $3.4m.

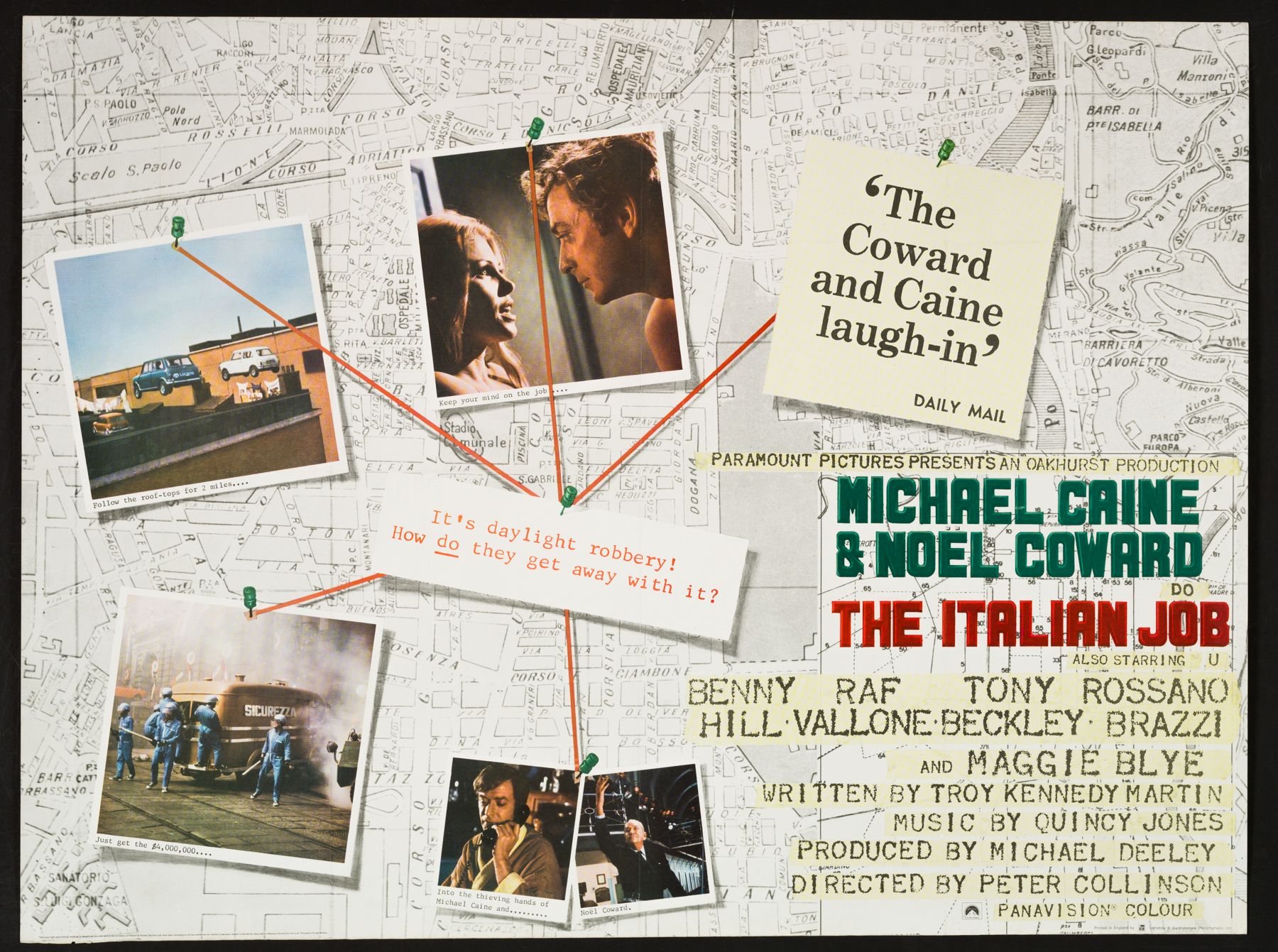

The Italian Job (1969)

This bank heist caper starring Michael Caine famously opens with an Alpine vista, soft jazz, and a Lamborghini Miura P400 threading its way through the mountains. Everything is perfect until the mob intervenes with an inconveniently placed Caterpillar bulldozer. Five minutes into the film and we have wanton destruction of an iconic sports car - or so it seems...

In reality the filmmakers were not so heartless - the chassis destroyed was a real, albeit written-off Miura supplied by Lamborghini, who also lent the colour-matched car used for the driving scenes to the production before it was delivered to a customer in Rome. More destruction of classics occurs later at the hands of the mafia, who dispose of two E-Type Jaguars and an Aston Martin DB4, although the Aston chassis flying down the gorge is actually a hastily resprayed Lancia Flaminia Cabriolet due to a foul-up with premature explosive special effects which forced a reshoot of the destruction. Six Alfa Giulia Ti police cars were also used for the film, only one of which survived.

Can you spot how the supposed Aston Martin DB4 Volante's bonnet opens the wrong way when rolling down the hillside, a giveaway to the mocked up Lancia used?

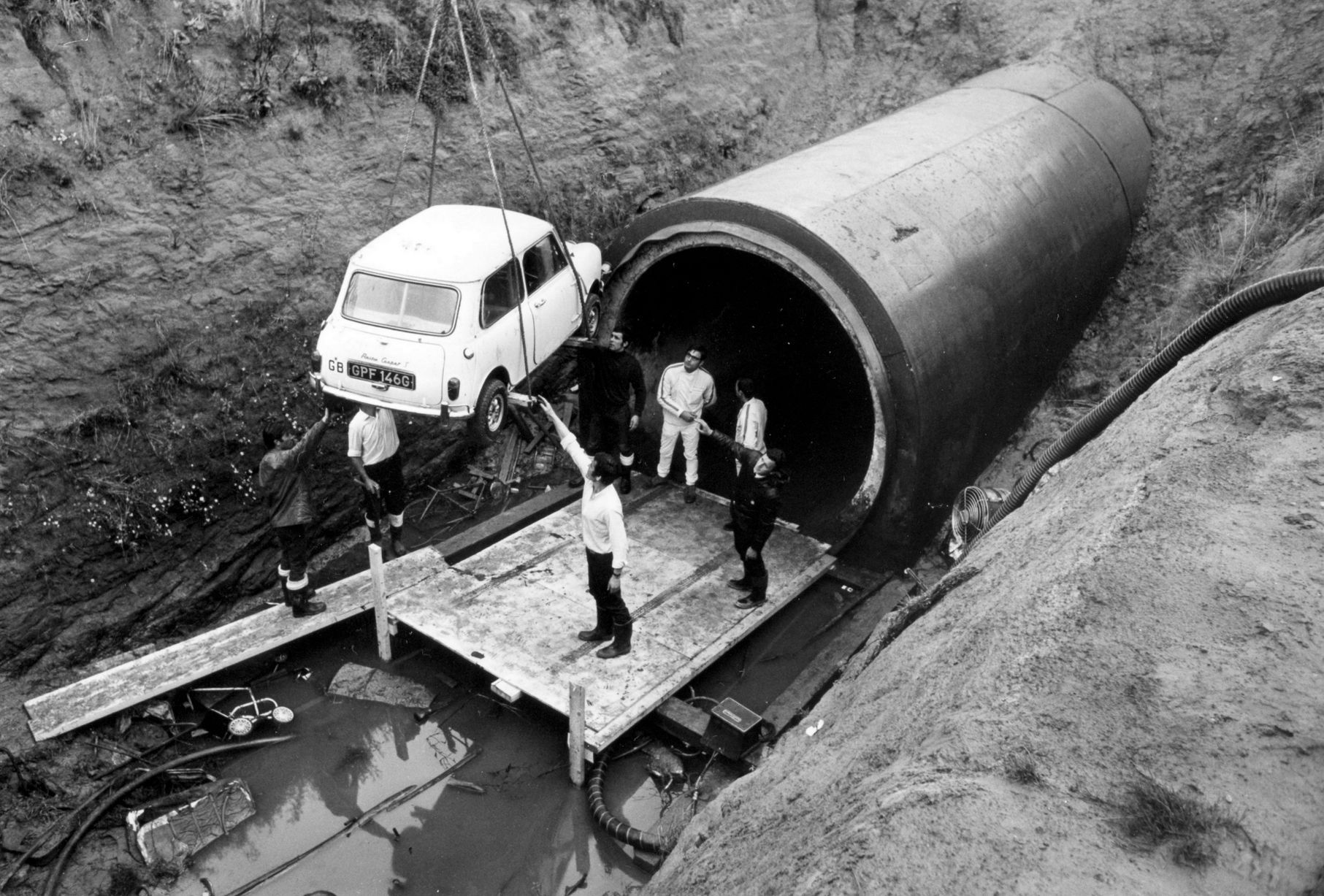

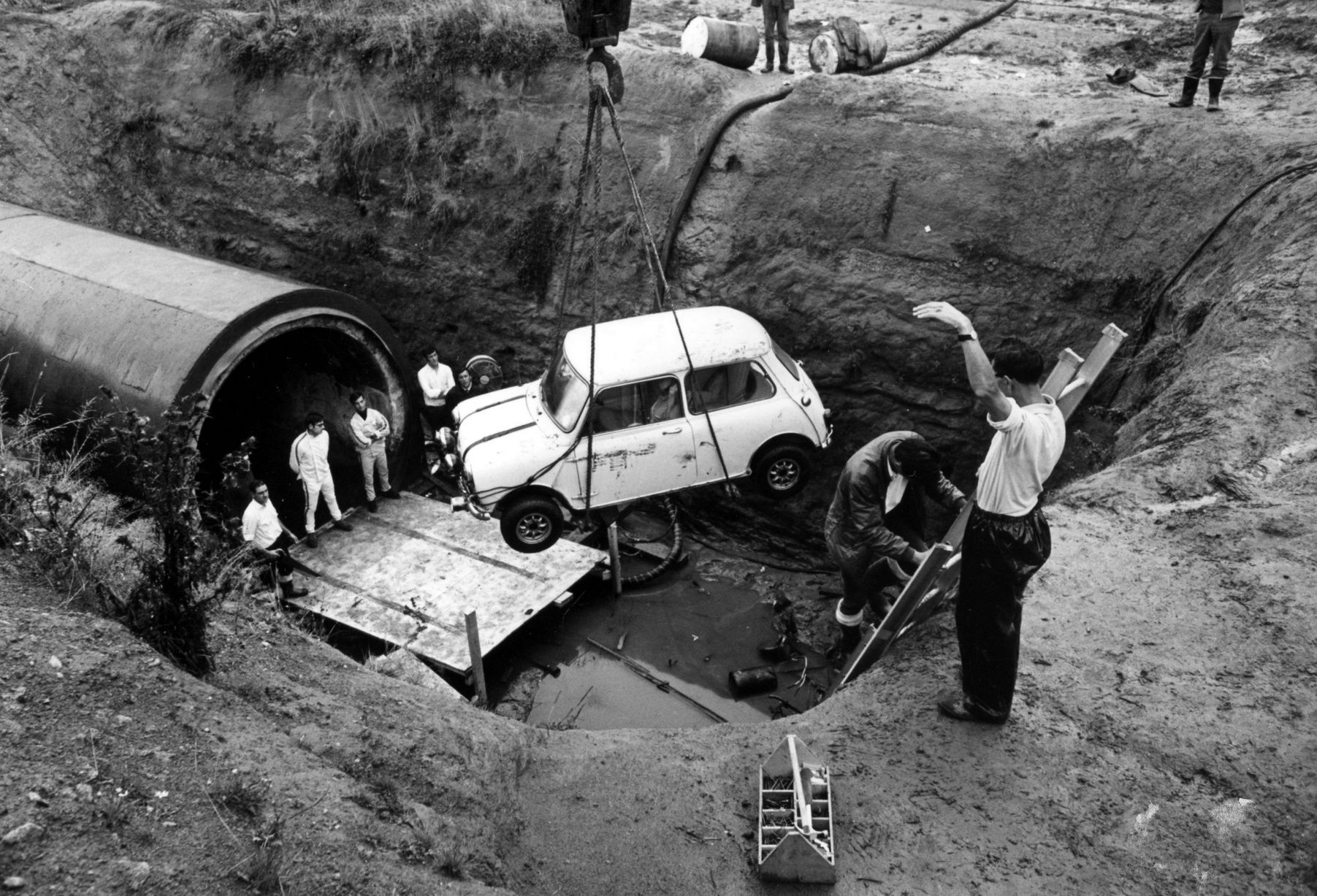

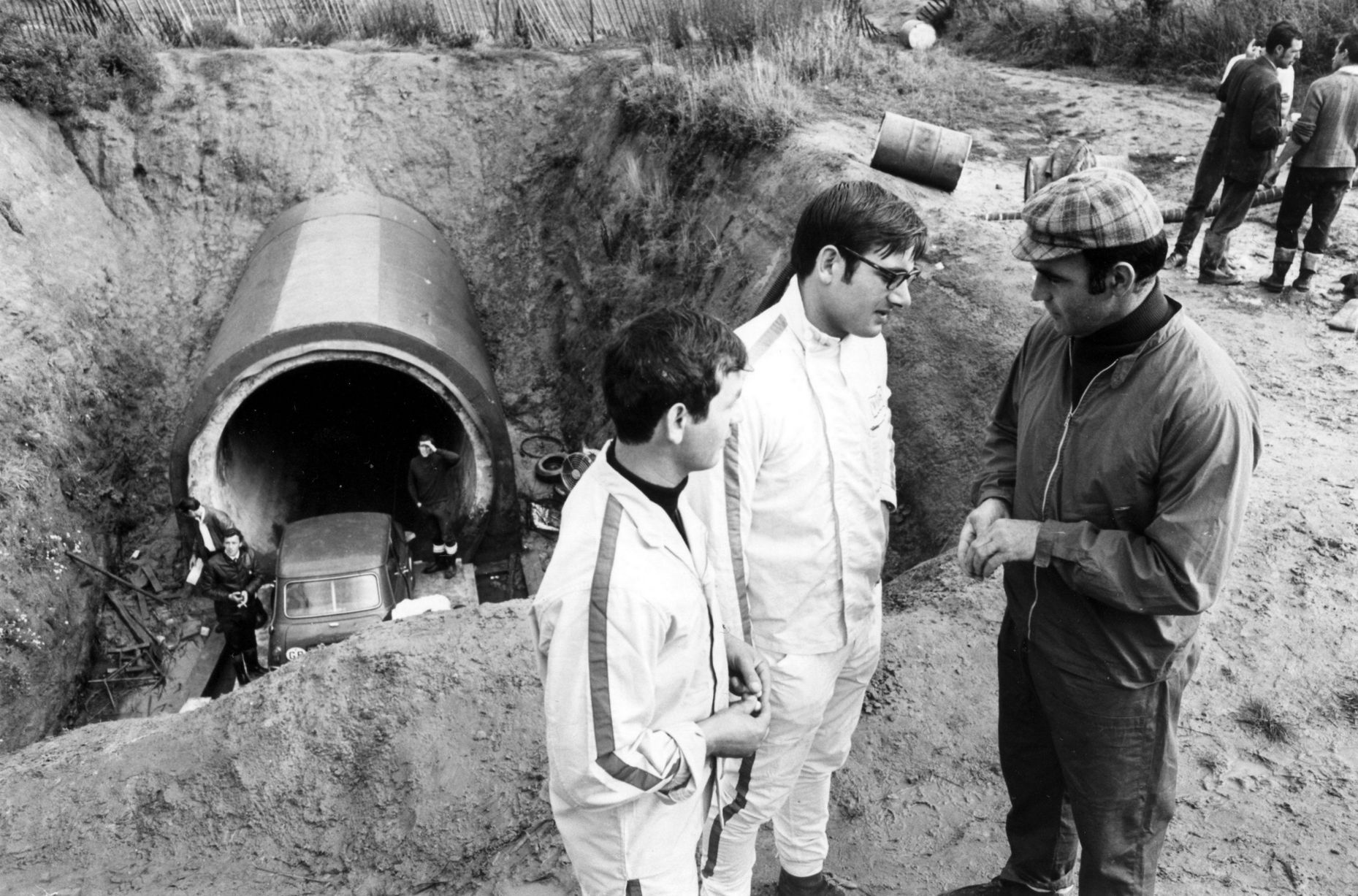

Of course, The Italian Job is mainly famous for its cheeky trio of Mini Cooper S cars (chosen in spite of an uncooperative BMC, and Fiat offering as many Cinquecentos as were needed). Interestingly, despite the interiors being stripped out at the request of rallycross champion and chief stunt driver Rémy Julienne, the engines were left completely standard. All of the cars for the film (except for the Miura) were sourced by stunt driver David Salamone at as low a price as possible, and driven to Italy and back again after filming had concluded. No transporters were used, and it was a case of all hands on deck: even David’s mother drove one of the E-Types. On his return to London stunt driver Barry Cox was stopped by police for speeding, which proved doubly unfortunate as he realised that his registration number as well as the tax disc were fake, and the boot of his white Mini was full of movie-prop gold bars. A night in the cells followed before he was rescued.

The Minis in Coventry sewers at Stoke Aldermoor, during the filming of the famous sewer scene on 26 September 1968. Source: Coventry Life

A better sort of intervention came from Gianni Agnelli, head of Fiat at the time, who put a good word in with Turin police to allow the production to bring Turin’s plazas and piazzas to a halt for filming. However even Mr Agnelli could not procure an appropriate Italian sewer, so that part of the famous final chase scene was shot at home in Coventry. The ultimate irony of the film is that Michael Caine did not receive a driving licence until he was 50 - which explains why he spends most of the chase in the passenger seat telling his co-driver to ‘look for the bloody exit!’

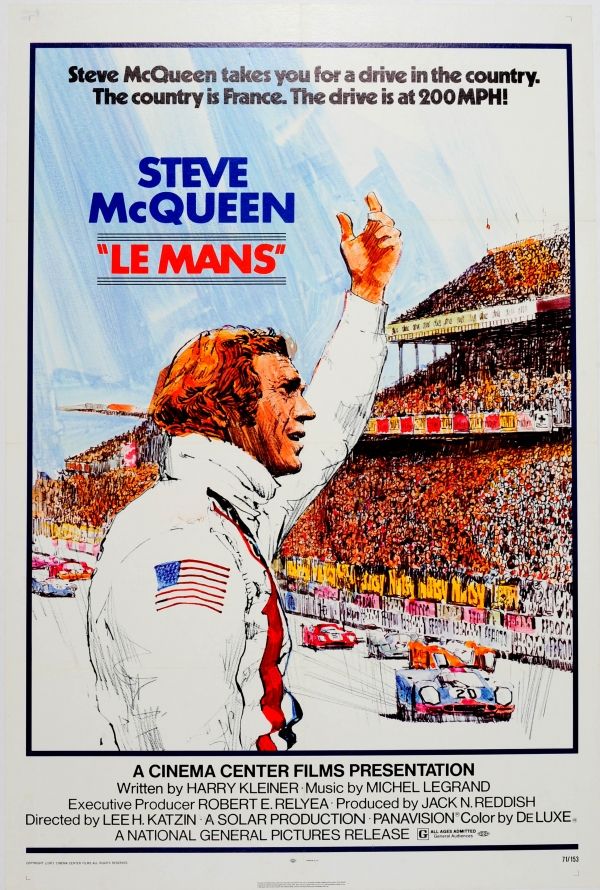

Le Mans (1971)

Le Mans was Steve McQueen’s attempt to bring endurance racing to the big screen, with no compromises. As a film it tests even the most committed viewer, with reel upon reel of race footage and the endless shriek of racing engines. There are around a hundred words of dialogue and a lot of doleful staring into the distance; no words are uttered for the first 37 minutes. McQueen had wanted a film for purists, an arthouse production with a Hollywood budget; as production difficulties increased director John Sturges begged him for a plot. None emerged from the several adjacent caravans of scriptwriters on set, as McQueen’s obsession for veracity took over.

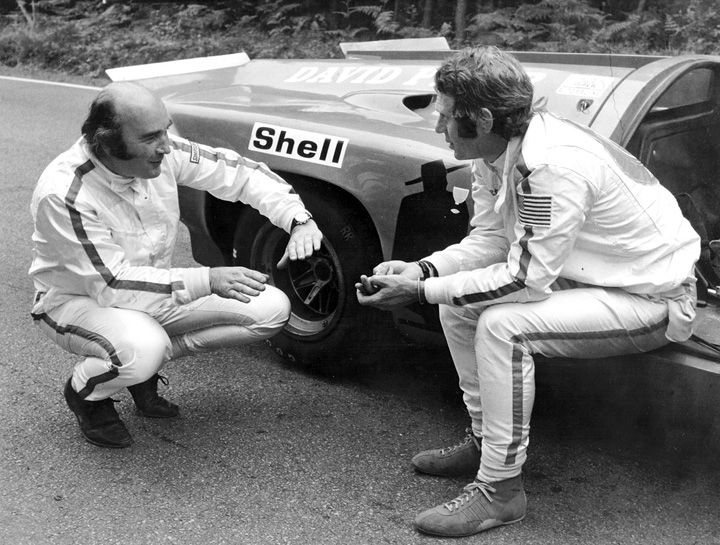

The racing footage was captured during the 1970 Le Mans edition by the non-classified Linge/Williams Porsche 908/2, with the backing of the Porsche factory, happy that the original script specified a Gulf-Porsche victory. After the race the track was rented by McQueen’s production company for 12 weeks and lavishly supplied: over 30 racing cars were used, including five Porsche 917s (one of which was Brian Redman’s), four Ferrari 512s (supplied by Jacques Swaters’ Ecurie Francorchamps), and two Lola T70s, one of which was sacrificed in a remote-controlled crash. The sounds heard in the film are all true to life, the takes are at real racing speed, and racing drivers of the time were also employed at significant expense to drive the cars, including the 1970 Le Mans winner Richard Attwood as well as Derek Bell, Jo Siffert, and Vic Elford amongst others.

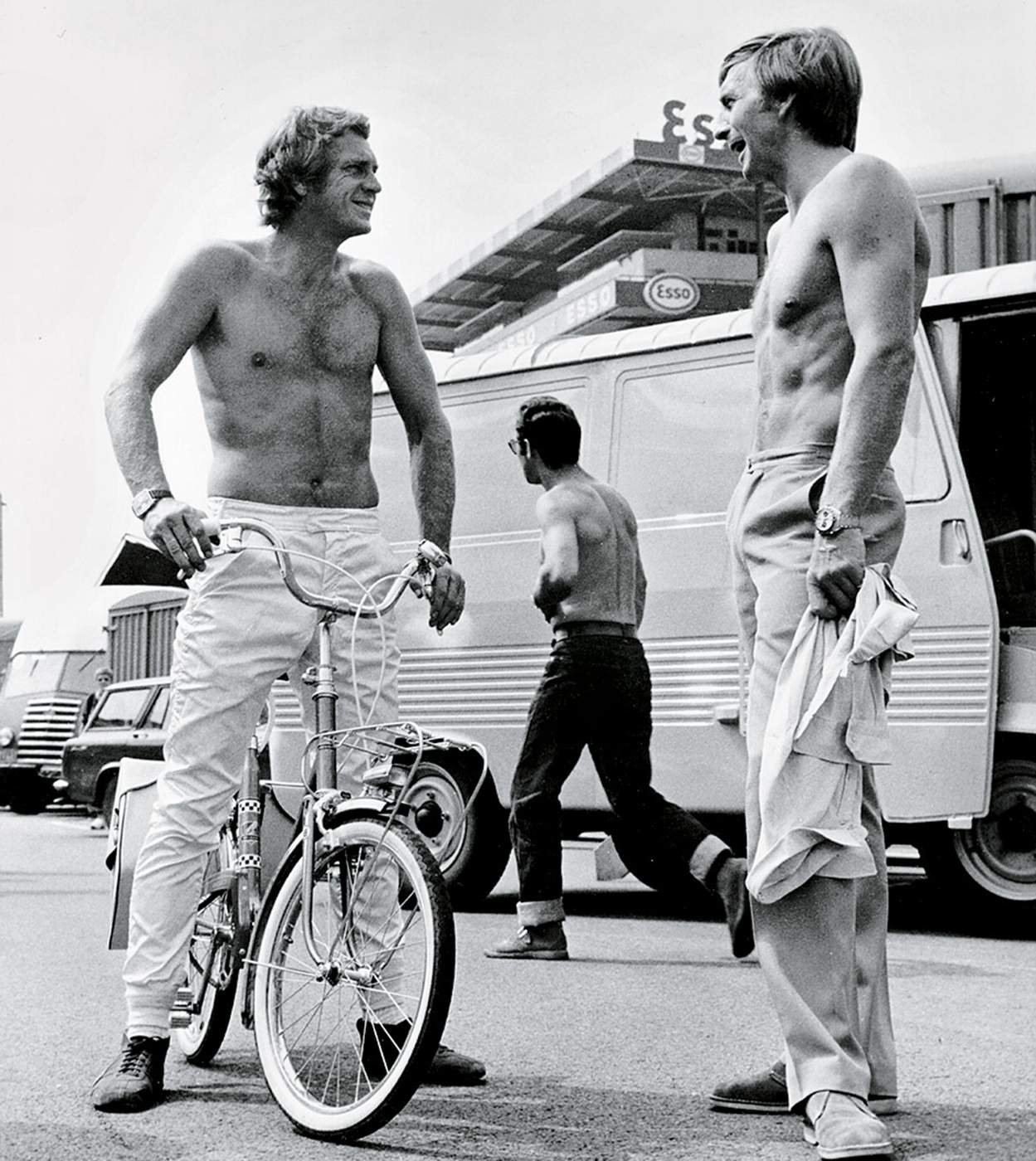

Top photo: Steve McQueen with Derek Bell. Group photo: Mike Parkes, Jean-Pierre Jabouille, Gerard Larrousse, David Piper, Jonathan Williams, Steve McQueen, Derek Bell, Masten Gregory, Hughes de Fierlant, Herbert Linge and Lee Katzin. Right photo: Steve McQueen chatting with David Piper. Credit: unknown.

Driving at real speeds meant that filming was as dangerous as the racing. Derek Bell suffered minor burns after his Ferrari 512 caught fire before a take; sports car driver David Piper lost part of his leg after a crash in his Porsche 917. At one point McQueen himself decided to lie down on the Mulsanne Straight to capture footage of passing cars; the insurers were not amused. By the end of filming the production was suffering conflicts, budgetary woes, and shooting delays (in one instance forcing the team to paint autumn leaves green to match summer footage). Somehow McQueen dragged it over the line, and the final product, while flawed and poorly received at launch, has survived as one of the cult pieces of cinema for committed petrolheads.

The Fast and the Furious (2001)

Beloved by teenagers the world over and feared by parents looking to prevent their children - largely male, ages 14-30 - from being sucked into the Los Angeles street racing scene of the early 2000s (now as much as then), The Fast and the Furious is the most guilty of pleasures: a mindless car-based action flick following the dilemmas of an undercover cop, with B-movie grit and ambitious A-grade stunt work. The cast are improbably good looking, the cars impossibly fast, and the action blasts through a Southern California awash with nitrous oxide and gangs of 1995 Honda Civics liberating stereo equipment from passing trucks. A far cry from more genteel automotive cinema, The Fast and the Furious brought an underground culture of reckless street racing and customised Japanese cars to the big screen, at a stroke showing legions of young people what they were missing out on.

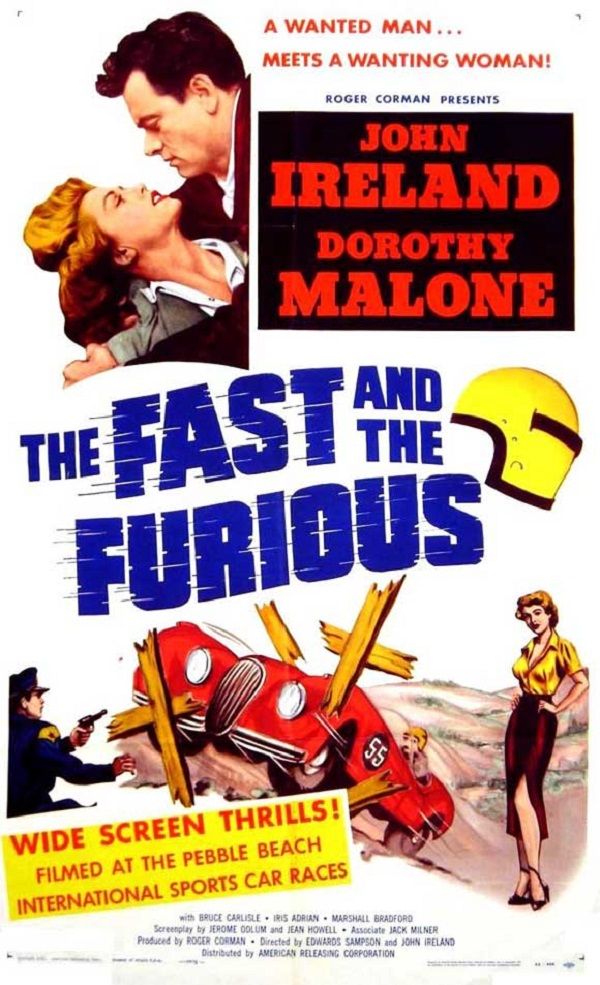

The script was inspired by Kenneth Li’s May 1998 article in Vibe Magazine entitled ‘Racer X’, describing underground street racing in New York. Curiously, the title of the film was licenced by Universal from a Roger Corman B-movie from 1954 about a man who breaks out of prison, steals a car and attends a race in Mexico. Thankfully the dubious tagline (“when a wanted man meets a wanting woman!”) was not.

Given the modest budget of the first Furious film, Universal Studios tasked technical director Craig Liberman (then director of the National Import Racing Association) to rent the chosen ‘hero’ cars from owners in the tuning scene and then cosmetically replicate them for stunts using cheaper cars of an identical year, make and model. Before long the 1995 Toyota Supra Turbo, 1996 Mitsubishi Eclipse and the 1993 Mazda RX-7 were on their way to becoming screen icons for a generation of teenagers, although the film also showcases American muscle cars such as the Dodge Charger and Chevrolet Chevelle.

While today the tuner car culture featured in the original film has moved on, along with neon underglow and absurd wings (mostly), and the current iterations of the sprawling $5bn Furious franchise have shifted away from street racing, The Fast and the Furious remains a film which contributed to the popularity of customisation of modern cars, as well as the idea that high performance is something attainable by a regular motorist with a turbocharger. And, of course, we have Furious to thank for Vin Diesel, probably the most appropriately named actor to ever star in an automotive film.

Rush (2013)

With music from Hans Zimmer and directed by Ron Howard, Rush saw the public flock to theatres to watch the battle between James Hunt (Chris Hemsworth) and Niki Lauda (Daniel Bruhl) during the 1976 Formula 1 World Championship. A slickly edited film, it makes racing’s death’s-edge romance accessible to the average moviegoer. Daniel Bruhl’s outing as Niki Lauda in particular is uncannily accurate - so much so that both Bernie Ecclestone and Lauda himself were reported as having enjoyed it greatly. Our previous Apex interviewees, Lord Alexander Hesketh and Freddie Hunt, son of James Hunt, were less complimentary with Lord Hesketh saying he thought it was "absolutely f**king rubbish"! Definitely worth a listen to those Apex interviews if you missed them.

Initially Howard had planned for extensive CGI to recreate the racing action; however a visit to the Nürburgring Oldtimer meeting shortly before filming influenced a shift towards using as much real car footage as possible. Unsurprisingly, Hunt’s original McLaren M23 and Lauda’s Ferrari 312 T2 were only used for close-ups, with a pair of rebodied Formula Vauxhall-Lotus and Formula Renault single-seaters used for action shots. While the six-wheeled Tyrrells shown in the film are the real thing, a number of original grid cars could not be sourced, so Ligier-Matra and Brabham-Alfa replicas with Rover V8 engines were commissioned along with two 1973 BRM P160s for scenes showing Lauda’s early career.

While the racing is excitingly shot, the eagle-eyed obsessive will note that the tracks on the 1976 calendar bear striking resemblance to parts of Snetterton, Donington and Cadwell Park. Brands Hatch (doubling as itself and, improbably, Monza) and the Nürburgring were in fact the only original 1976 venues used, and most of the film was shot at Blackbushe airfield near London on a mocked-up pit lane and grid masquerading as the circuit of choice. When filming at the tracks, cars would also be run in both directions to fit the particular corner profile needed for a shot. Despite some forgivable inaccuracies, such as an overly played-up personal rivalry between Hunt and Lauda, modern OMP logos on race suits and an odd reference early on to the Nürburgring as “The Boneyard” rather than the “Green Hell”, Rush remains a deeply enjoyable modern racing film.