How To Be A Gentleman Driver

With garages across the country echoing with the sounds of engine revs and with the 2021 edition of the Monaco Historique Grand Prix coming to a close this afternoon, the Apex team has been turning to our venerable motoring library to rekindle our passion for racetrack exploits, or at the very least inspire some B-road brilliance. Our ‘speed read’ of choice this week is ‘Racers’, a lavishly illustrated tome from the Palawan Press which captures the stories of sports car racing’s ‘golden age’ of the 1950s and ‘60s in the words of the drivers who were there. We’ve decided to tug on a few of the more curious threads from this tapestry of tales, so that in case you ever find yourself in charge of a fine vintage sports car, you’ll know exactly how to conduct yourself.

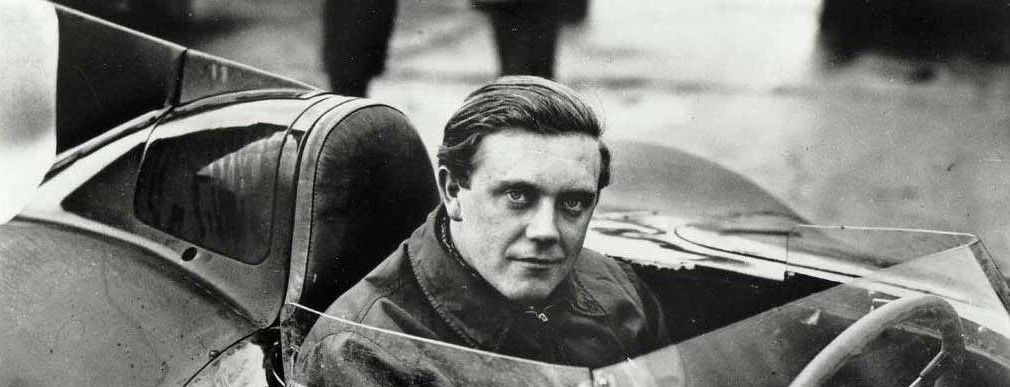

Credit: Palawan Press

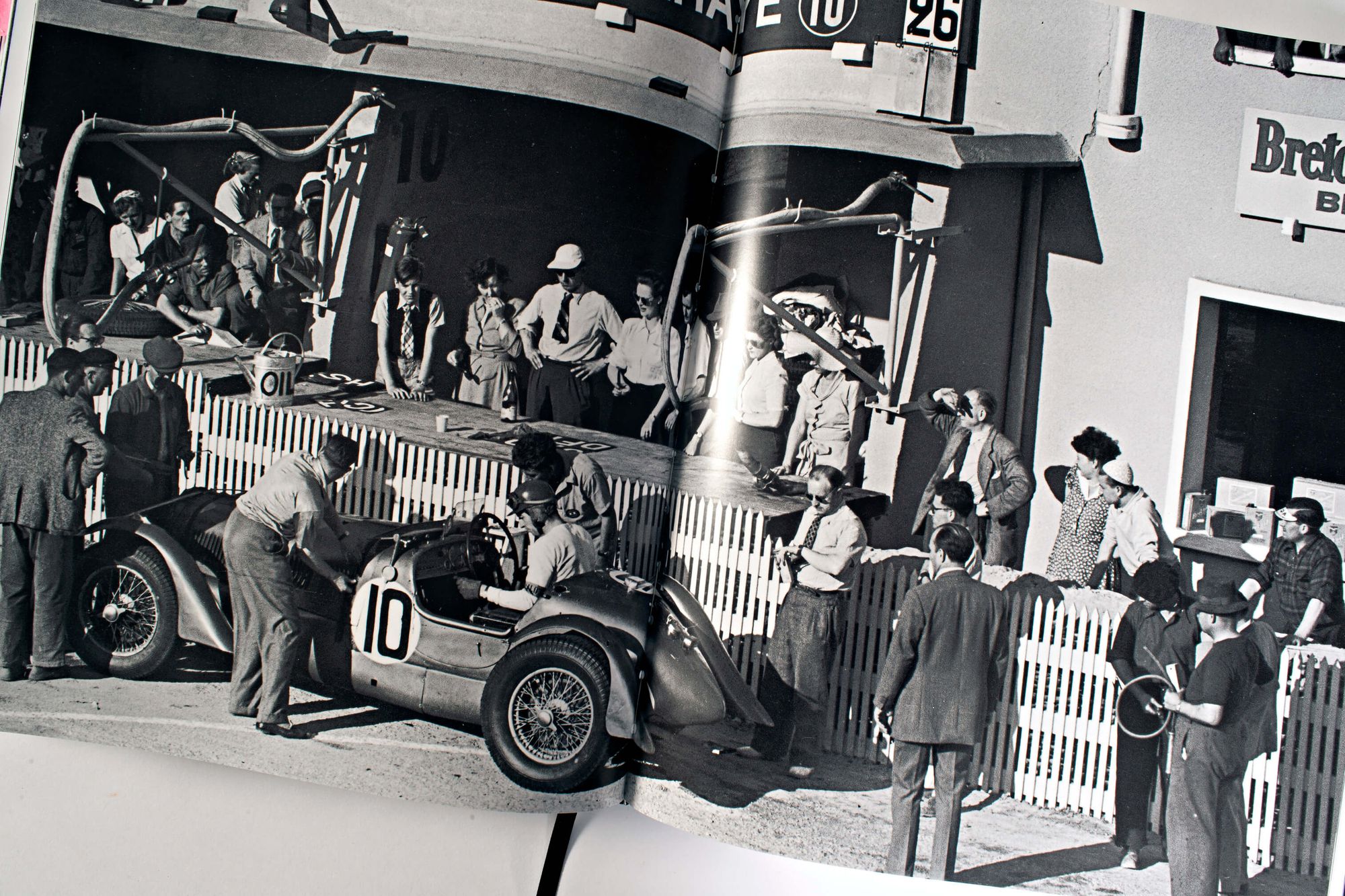

Anthony Pritchard’s ‘Racers: Memoirs of the Gentleman Drivers’ is a book by and about those drivers who, regardless of ability, enthusiasm, or finances, found themselves at the pinnacle of British and European sports car racing in the 1950s and ‘60s. Ex-soldiers, farmers, trained engineers or simply lucky beneficiaries of a good inheritance, none of the 25 drivers interviewed by the author were ‘professionals’ in the modern sense of the word - which makes their stories all the more interesting. Published in 2011 by the Palawan Press as a limited edition of 525 numbered copies, ‘Racers’ is a wonderfully presented collectors’ publication which rewards multiple reads, not least for its extraordinary period photographs. It also contains the following lessons for anyone, like certain members of the Apex crew, who would fancy themselves gentleman driver material if given a time machine and a few weeks off work…

Written by Hector Kociak for The Apex by Custodian. Edited & produced by Charles Clegg and Guillaume Campos. Many thanks to Palawan Press (https://www.palawan.co.uk/) for lending us the book to review.

1. Be Charming Off Track, Cunning On Track

In the 1950s, high-level racing was not what it is today, with established sponsorship structures, bureaucratic racing teams, and vast budgets. You had to make your own way. What strikes you about the accounts in ‘Racers’ is just how resourceful and headstrong drivers had to be to even get into contention. Take Tony Rolt, who proudly tells the story of somehow wangling an international entry to the 1936 Spa 24h at the age of 17, having just lost his driving licence in Britain for speeding in Denbigh High Street in his Triumph Southern Cross (as it turned out, he came fourth in class). Not surprising to learn that he would later have eight attempted escapes while a PoW in WWII to his name, along with a Military Cross and role as glider-builder in a planned escape from Colditz.

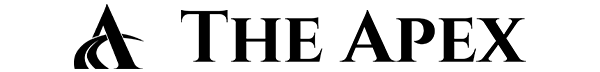

1936 24 Hours of Spa-Francorchamps. Source: Motorsport Images

If track work is your thing, take inspiration from a young Peter Blond (later car collector and textile entrepreneur), who decided a month prior to the 750 Motor Club Six Hours Handicap Relay of 1953 at Silverstone to simply lift the barbed wire around the circuit one afternoon and take his Jaguar XK120 out for a bit of practice. He got a stern telling off, but God knows what would happen if you tried that today. And if it was a money problem you faced, you could always take the Kenneth McAlpine approach, who realised that it was cheaper for him to run the Connaught racing car business as a loss-making concern than it was to actually pay for racing out of his taxed income. Any excuse, right?

2. Be Your Own Mechanic

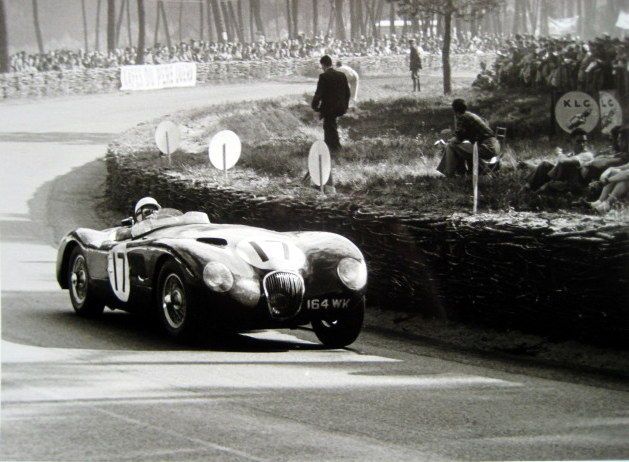

Today, we have the luxury of ‘arrive and drive’, with some amateur racers barely ever seeing a bearing or a sprocket at a race meet, and manufacturers leaving their mechanics to handle race day tasks. In the 1950s, not only did drivers constantly have to dive under the bonnet to come up with solutions themselves - things were a bit more involved for everyone. Bob Berry found himself as a volunteer in the extremely lean Jaguar works team at Le Mans in 1951, and recounts watching none other than Bill Heynes, Jaguar’s Director of Engineering, in the pits trying to hammer out improved headlamp cones from sheets of aluminium. The man clearly hadn’t touched a hammer since his apprenticeship days - and things didn’t seem to improve much in the following years. Apparently Stirling Moss commented at Le Mans in 1953 that his C-Type lights shone like “constipated glow-worms”; the Jaguar drivers at night largely followed the flames coming out of the leading Ferrari exhausts!

Bob Berry in a Jaguar D-Type. Source: Porter Press // Credit: unknown

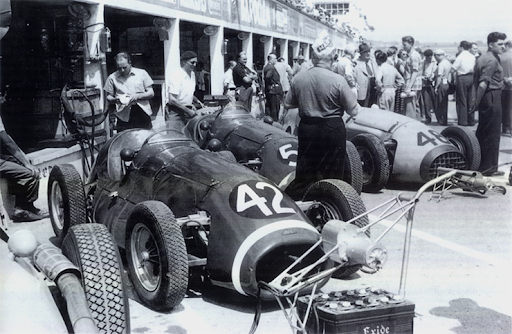

In reality, British drivers of the post-war period were not in the position of domestic Ferrari or Maserati clients, able to demand small-batch precision engineering of a camshaft here or a piston there from their manufacturer. Kenneth McAlpine’s account underlines how in the 1940s and 50s, even for a race car manufacturer like Connaught, insisting that everything mechanical had to be exactly right was “quite novel”. Even if you had an Aston or a Jaguar, it was more often a case of making do, finding a local machine shop, or even sketching and fabricating your own parts while navigating constant breakdowns and mechanical failures. Reading some of these stories, it remains a wonder that the sports cars and single seaters of the period (including the iconic Connaught A-series and Lotus Formula 2 cars) often ran at all.

Kenneth McAlpine and his Connaught. Source: F1ForgottenDrivers.com // Credit: Rob Petersen

3. Beware The Troubled Brilliance Of Lotus

One of the curious unifying themes of almost every interview in ‘Racers’ is Colin Chapman, or more precisely, how procuring and maintaining a racing Lotus in-period seems to have been a task fraught with disappointment and frustration. Imagine for a moment you are Mike Anthony, a keen enthusiast racing for Team Lotus in 1954. You get a call from Mr Chapman offering to install innovative Dunlop disc brakes on your new Mk X Lotus-Bristol - for a price, of course. You agree. They need a bit of pumping sometimes, but nothing too bad. Months later you bump into a Dunlop disc brake representative at the Charterhall race meeting. He asks how you are getting on with the ‘experimental’ disc brakes given to Lotus to test on your car…! Unsurprisingly, a legal tussle ensued.

It was not much better at the factory. As John Lepp puts it, the Lotus Elite was God’s gift to motoring, the only problem being bits of rubber coming out of places bits of rubber were not supposed to come. Even if you turned up in a Bentley, it didn’t prevent you from getting, for example, an Elan with no engine. Stories of Frankenstein cars abound, but some drivers treated it as a bit of a game. Despite having no spade and having to dig his beached Lotus out with a headlamp cover at Le Mans in 1958 (“with Chapman you didn’t get anything!”), Michael Taylor continued to buy Lotus racing cars until a serious accident at Spa in his Lotus 18 - although he would always do it at about 12.30pm on a Friday afternoon, when Mr. Chapman needed wage money to be in the bank by 3pm. Things have improved since the ‘50s, thankfully.

4. Know How To Tame A Jaguar

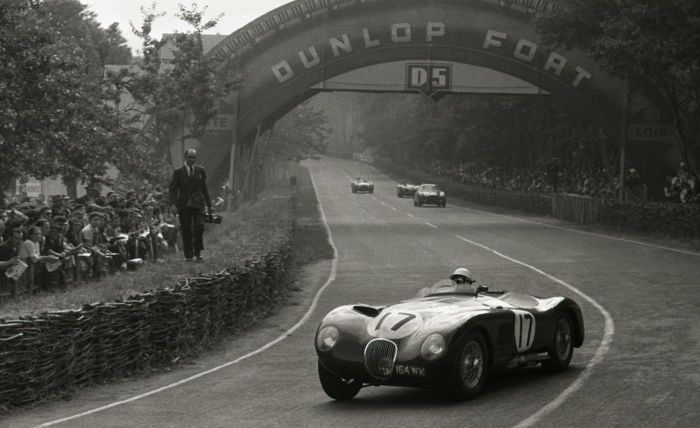

Whether it was your first car being a SS100, a country jaunt in a XK120, club racing in a C-Type or Le Mans in a D-Type, to be a gentleman driver in the ‘50s and ‘60s was to know your way around a Jaguar, and quite often, out of one after putting it in a ditch or a hedge. Over half of the interviewees in ‘Racers’ have a strong connection with the marque, and it is hardly surprising given its popularity with racers in the era. The imposing 6’ 5” figure of team manager Lofty England would often be found floating across club racing paddocks, finding ways to get the best drivers of the day into Jaguars and possibly into the works team. If you weren’t racing a factory Jaguar, you were probably using one of their engines, or at least some disc brakes as proven at Le Mans by team C-Types in 1953. Such was the reputation of these workhorse cars that even Jimmy Stewart, irritated with the substandard performance of his Aston DB3S at Le Mans in 1954, complained that he would rather have had his C-Type there!

Le Mans 1953, Stirling Moss / Peter Walker in a Jaguar C-Type. Credits: LAT Photographic

Most important to the gentleman racer was customer service - of the 1950s sort. Jonathan Sieff recalls it being exemplary, in that you could smash your big cat up at a race meeting and Jaguar would often have it rebuilt by the next weekend. Sometimes an engine rebuild would be done as a matter of courtesy during a regular service. Racing driver Peter Sutcliffe was also a frequent customer of the engineering department (unfortunately due to a number of incidents in his lightweight E-Type), so much so that he recalls a nonplussed mechanic once meeting him with the immortal words: “Hello Mr Sutcliffe. You’re here again. What is it this time? Can we wheel it in or do we have to get a shovel?”

5. Accept The Risks

While many of the stories we read about the golden age of racing are rightfully humorous, it is sobering to think of the extraordinary risks taken at a time when the science of car safety was in its infancy. Many amateur racers suffered terrible injuries in their careers - some of them permanent, all of them shocking, not to speak of those who sadly lost their lives doing what they loved.

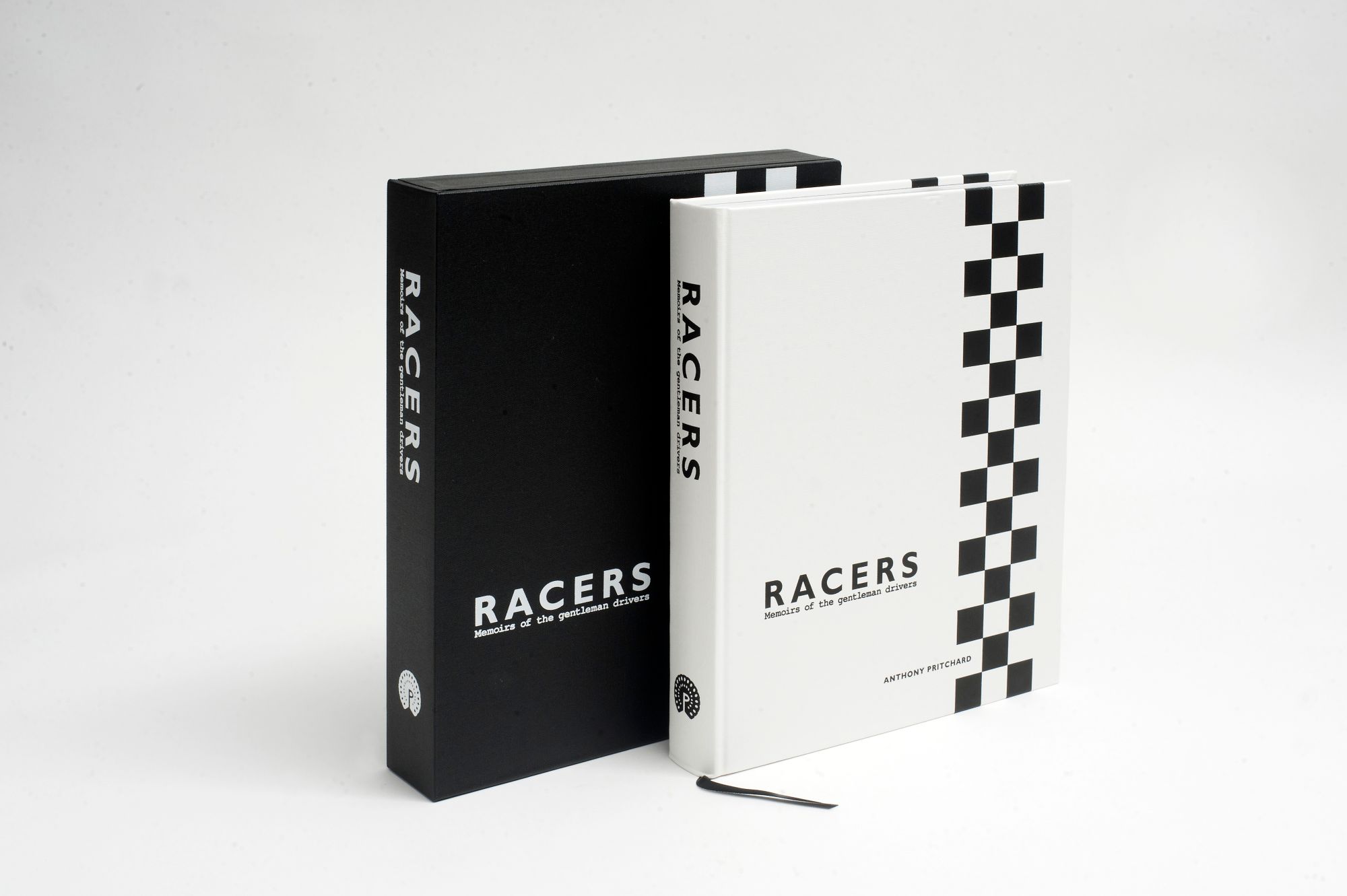

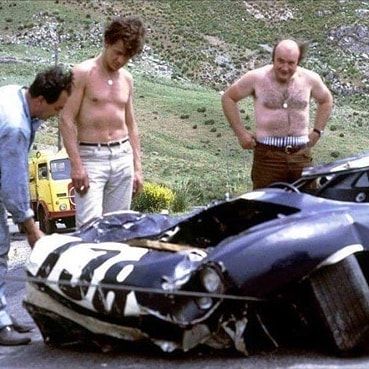

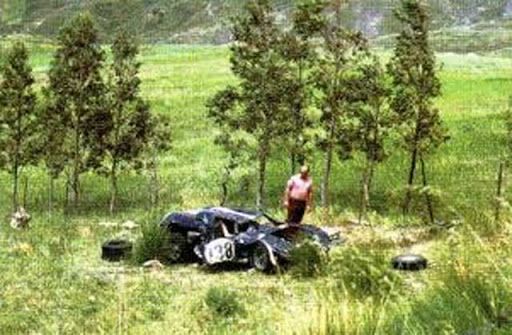

There are many lucky escapes covered in ‘Racers’ too - Keith Hall being violently flung out of his Cooper-Bristol at Crystal Palace in 1954, Noel Cunningham-Reid hitting a tree in his HWM Jaguar at Oulton Park and ending up in a lake, or Jimmy Stewart going through a hedge upside down at speed at the Nürburgring in a D-Type in 1955, only managing to turn the ignition off with his foot. There were thousands more incidents like that. Reading accounts of shorn rear wheels, brake failure, and other troubles, it is staggering to think how racers of the time could nonetheless strap in and feel that they were immortal. As Sir Paul Vestey also wryly notes in his account, if the racing was not dangerous enough, the locals were another story – as he and David Piper found out on the Targa Florio in 1968, when their crashed Ferrari 250 LM was pillaged overnight by locals who stole all the dials and cut out the seatbelts.

David Piper's Ferrari 250 LM after rather a large 'off' during the 1968 Targa Florio. Source: GP Library // Credit: P Vestey

Of course, the dangers were more pressing and immediate for families and friends of these drivers. Saloon car hero Tommy Sopwith moved away from open wheel racing at the request of his family, and many of the gentleman racers eventually hung up their helmets as the culture of racing changed and the potential costs, in all senses, became too much to contemplate. We might look back fondly on the period where the cars were beautiful and the racing was pure, but as you strap on that helmet for an afternoon of thrills, it is also worth remembering that old adage: motor sport can be dangerous.

To find out more about Anthony Pritchard’s ‘Racers: Memoirs of the Gentleman Drivers’ and other books published by Palawan Press, please visit their website at https://www.palawan.co.uk/.